• How did the idea of starting a ‘Community Publishing’ model come up?

Books have been my mainstay for as long as I can remember. Thus, entering the business of making books was a natural enough choice coupled with the fact that I had read Literature at Calcutta University and Fergusson College in Pune. It all came together, and I trained in publishing as a book-editor.

Books have been my mainstay for as long as I can remember. Thus, entering the business of making books was a natural enough choice coupled with the fact that I had read Literature at Calcutta University and Fergusson College in Pune. It all came together, and I trained in publishing as a book-editor.

But even as I immensely enjoyed my work, I became acutely aware of the uncomfortable fact that while print and its institutions could be empowering for some, it could prove just as discriminating and disempowering for many—who cannot participate in its literacy- and technology-driven systems with agency and authenticity,simply because their traditional communication means happen to be vastly different from the dominant one. They certainly do not author books or buy them.Books are always about them.

That was where I felt change had to happen. I initiated Participatory Publishing Praxis as a way of working towards this—basing textual practices in social situations of dialogue exchanged within community life in the local milieu. The text emerges as transcription of this essentially oral, spontaneous collective communication of the group, quite unlike what happens in traditional print publishing which begins with the written or typed manuscript as the inscription of the individual author. We always try to integrate a book arising out of community reflection and dialogue with some kind of concrete action towards that community’s development.

Kumartuli Work in Progress

Kumartuli Work in Progress

• What draws you to work from Bengal?

I have lived in quite a few cities in India and abroad. There was a time when I had felt an overwhelming need to uproot and leave and I responded by choosing to live and work in other places. I returned because I felt I sort of had unfinished business here. And, sure enough, it was in Bengal that I found the opportunity and the people amongst whom I could first put my ideas into form. I now feel the need to stay, to stay on and grow roots in my backyard, and so here I am. Home is where the heart is.

• What work are you doing with artisans of Kumortuli? Do you plan to showcase the lesser known artists to the world platform?

I have been interested in Kumortuli clay-artists’ community for some years now—first exploring the lanes to familiarize myself with the place and the people,then accompanying Fulbright scholar Cynthia Siegel, who has done substantial scholarly work there, and who helped very generously with the initial introductions. My first impression was that Kumortuli was very much a man’s world. But soon enough I discovered a group of women in the locality who have acquired quite a prominent position. They are skilled artists as well as entrepreneurs and have set themselves up in their own studios from which they do business with far-flung places across the world.

Pingla Book Launch 2014

Pingla Book Launch 2014

Notable among them are Mala Pal and China Pal. Again, there are many more women who do not necessarily operate in their own name or out of their own establishments, but do help out in the family business. I got to know of mothers, aunts, grandmothers who had always been involved in the clay craft, but never really acknowledged outside of the family structure.Furthermore, there emerged the memory of one exceptional woman artist a pioneer from the earlier generation who had plied her trade, singlehandedly and publicly—the first woman in her generation. Our upcoming publication Mritshilpo Matribhasha explores her story along with stories of women artists today.

• You worked on a project called ‘Children of Midnapore.’ What was it all about?

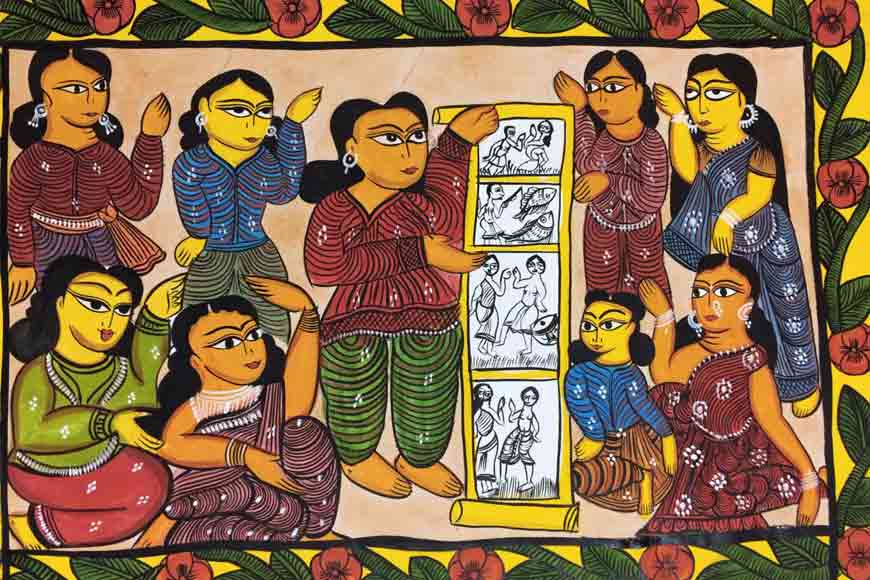

My first project where I got the opportunity to field test the process happened in 2014 in Naya village in Midnapore as that is where an entire community of patachitrakars—traditional scroll painters and singers—are settled. There the children and their parents—the entire village—participated in making their own book—based on their re-interpretation of Sukumar Ray’s chhora ‘Murkho Machhi’—a dialogue between a fly and spider, prey and predator, expanded to examine issues in their lives and art. What they gleaned from that first experience of inter-generational community discussions brought up the topic for their next exploration—the practically forgotten origin-myth of the patua community, which the children reconstructed from the recollections and songs of the earlier generations—helped along by the legendary Dukhoshyam Chitrakar.

My first project where I got the opportunity to field test the process happened in 2014 in Naya village in Midnapore as that is where an entire community of patachitrakars—traditional scroll painters and singers—are settled. There the children and their parents—the entire village—participated in making their own book—based on their re-interpretation of Sukumar Ray’s chhora ‘Murkho Machhi’—a dialogue between a fly and spider, prey and predator, expanded to examine issues in their lives and art. What they gleaned from that first experience of inter-generational community discussions brought up the topic for their next exploration—the practically forgotten origin-myth of the patua community, which the children reconstructed from the recollections and songs of the earlier generations—helped along by the legendary Dukhoshyam Chitrakar.

This narrative of mythical origin the children created participatorily as pater gaan and patachitra which they performed at the local community festival in 2017. They are now creating their second book as compilation of the song, scroll and their experiences in community memory through the Participatory Publishing Praxis process. Also, while planning the accompanying action initiative they came up with the idea of a community school—which has been running in the local village centre since February 2018—where the children and even a few adults are learning from the community elders so that the collective repertoire of pater gaan, which is primarily dependent on oral transmission and tutelage continues to remain alive in the consciousness of the younger generation.

PPP Workshop in Kumartuli

PPP Workshop in Kumartuli

• You have also translated bits of Sukumar Ray. Do you have plans of further translations?

In the community discussions that took place at Midnapore, many of the mothers came forward with their hopes and aspirations for their children’s future. It was at this juncture that Rani Chitrakar voiced the need for the children to be fluent in the English language, conversationally and otherwise as they travel abroad a lot and find it very difficult to explain the verbal content of their songs without someone else mediating. This was supported by everyone present. So we decided to make this the community action-initiative that we could realistically complete within the limited scope of the pilot project. I was quite surprised by this course of action. I would never have thought of it myself. The children enthusiastically proceeded to translate Sukumar Ray’s ‘Murkho Machi’ into their version in English. Translating Ray was really their idea. I merely facilitated the session.

Origin Myth Pata

Origin Myth Pata

• How successful has been your publishing endeavour? Do you think children of today still read books?

Traditional publishing revolves around individual author and is completely graphocentric privileging writing over speech. Participatory Publishing Praxis turns this model on its head. So understandably, my peers and seniors in the publishing industry were initially very skeptical as to whether it is even possible to involve an entire community in the making of a book, particularly where literacy levels are mostly inadequate for the ‘authoring’ function as we know it , whether it is practicable to take the publishing process into social spaces it would ordinarily not go into, and to people who would usually not access it to speak for themselves,to represent themselves in print for their own purposes without losing identity. And that is a very complex navigation. But eventually a lot of support materialized. Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute, Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival and later the India Foundation for the Arts showcased our work. The Kumortuli project was featured as‘Kumortuli Rising’in the ‘One Billion Rising’ initiative.

Kumortuli Rising

Kumortuli Rising

Yes, I do think that children will continue to read books. But what is more important is that children will continue to be curious and continue to learn in the direction in which their curiosity leads them. Which could well be through books and through other ways and means that present themselves in time.The message will always find its medium.

• What are your plans for Bengal in the field of folk art and literature?

I am presently involved in planning a project with Aaron Ghosh within a Baul community—in a Bolpur akhra. It would be very fascinating and challenging to bring their traditional oral repertoire into the fold of the written word and print—which is literature and the kind of narratives we find in books—Two very different communication paradigms bridging two very different worlds and ways of life.