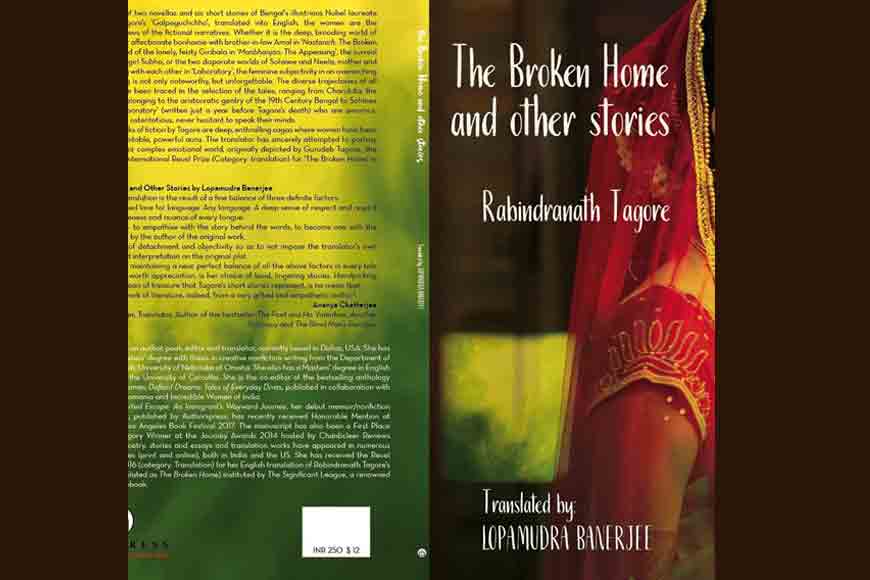

Lopa Banerjee’s ‘The Broken Home’ (Nastanirh)

The copious young clouds of the Bengali month of Asharh gathered in the sky. An inexplicable darkness crystallized in Charu’s room. Near the open widow, she bent over a notebook, scribbling in it, lonely, lost in her own furtive world.

She didn’t notice when Amal surreptitiously entered the room and stood behind her. Charu continued writing in the smooth, gentle light of the rainy day, and Amal continued reading secretly. There were a couple of Amal’s printed, published writings lying beside Charu, upon which she would model her own compositions.

“Why do you say that you cannot write, then?” Amal’s sudden utterance in the room startled Charu. She quickly hid her notebook. “This is so very mean!” She said.

Amal: “But what did I do, after all?”

Charu: “Why were you spying on my writing?”

Amal: “Because you won’t let me see it otherwise.”

Charu was about to tear up her writing. Amal snatched it away from her in a moment. “If you read it, I swear to never ever speak to you in this life,” Charu said.

“And if you forbid me to read it, I swear to never ever speak to you in this life,” Amal retorted.

Charu: “For heaven’s sake, do not read it, thakurpo!”

Finally, it was Charu who had to surrender. Deep within, her restless mind was eager to show Amal her composition, but she didn’t think she would feel so much shame and hesitation while actually presenting it to him. She ultimately gave in to Amal’s pleas as he started reading it out, but her hands, her feet froze in embarrassment. “Let me bring some betel leaves,” she said and left for the next room.

Upon finishing reading, Amal said: “It is wonderful!”

At this, Charu forgot to add khoyer, a condiment to the betel leaves. “You don’t have to make any more fun of me. Give me back my notebook,” She said.

Amal said: “No, you won’t get it back now. I will make a fair copy of this and send it to a magazine.”

“No, never, you won’t do that,” Charu said.

This created a ruckus between the two. Amal was unrelenting till the end. When he had sworn to her several times and convinced her that it was fit for sending out to publications, she gave in, albeit hopelessly. “It is so difficult to compete with you in anything. You are so invincible, really!” She said.

“Now I must show this to Dada too,” Amal said.

At this, Charu left dressing the betel leaves and lifted herself from her seat in haste. She attempted to snatch away her notebook from Amal. “No, you must not tell him about this. If you tell him, I will stop writing immediately,” she said.

Amal: “This must be a serious misunderstanding on your part, Bouthan. I am sure Dada will be elated to see your writing, whether he expresses it to you or not.”

Charu: “Let it be; I do not ask for his elation.”

Charu had promised to herself that she would start writing and give Amal a pleasant surprise; she thought she would not stop until she proves herself to be worthier than Manda. For the past few days, she had written quite a lot and then tore off the pages. Whatever she attempted to write became a replica of Amal’s writing. When she tried to compare both, she discovered that parts of her writing sounded as if they had been directly quoted from Amal’s compositions, and only those seemed good writing to her, the rest appeared raw, immature. Charu imagined Amal finding those parts and laughing at them, which made her tear up the writings to pieces and discard them in the pond, lest Amal happens to see even a bit of them by sheer chance.

The first composition she created was named ‘The Clouds of Shravan (monsoon)’. She had thought to herself that she had written a unique piece, seeped in the emotional fervor of her imagination. Suddenly, with conscious scrutiny, she discovered that the piece was very akin to Amal’s essay, ‘The Autumn Moon’. In his essay, Amal had written: “Dear moon, why are you hiding amidst the clouds like a thief?” And Charu had written: “Dear friend Kadambini, where did you appear from suddenly, and steal away the moon under your blue drape?”

But since Charu realized she was not able to transcend the literary boundaries set by Amal, she decided to change the subject of her compositions. Instead of the moon, clouds, the shefali flower, the Indian nightingale, she wrote a piece named Kalitala. There had been a temple of Goddess Kali near the silhouetted darkness of a creek in her ancestral village. She wrote the piece about the fertile imagination of her child’s mind, her fears, her curiosity, her queer, eccentric memories centered on the temple and the ancient myths of the village folks surrounding the greatness of the Goddess. The beginning of the piece had been influenced by the poetic opulence of Amal, but as she proceeded with the piece, it became defined by its earnest simplicity, replete with the linguistic nuances of a lucidly narrated village tale.

Amal snatched away this writing from Charu and finished reading it. To his opinion, the beginning of the writing was quite delightful, but the poetic effect was not maintained till the end. Anyway, this was quite a commendable attempt of a novice writer, he thought.

Charu said: “Thakurpo, let us start a monthly publication of our own, what do you say?”

Amal: “But how will it survive without enough of silver coins?”

Charu: “But there would be no investment in our publication. It would be hand-written entirely, no hassle of printing. It would only publish both of our writings, and nobody else will get access to it. We would release only two copies, one for you, and the other for me!”

Had it been some days earlier, Amal would have been enthused at this proposal. However, times had changed Amal, and he no longer loved these secret liaisons. He was not content these days unless he could address a herd of people in his compositions. Nevertheless, he maintained a façade of enthusiasm for old times’ sake and replied: “That would be great fun.”

Charu said: “But you have to promise me that you won’t publish your writing anywhere else apart from in our own publication.”

Amal. “But the editors would kill me then!”

Charu: “Is it? But don’t we have weapons to kill them as well?”

Thus, a committee consisting of two editors, two writers, and two readers was formed.

Amal said: “Let the magazine be named Charu-path (Charu-reading).” Charu said: “No, it would be named Amala.”

Charu had forgotten the anguish and irritation of the interim period, by virtue of this new arrangement. There was no way for Manda to enter their monthly literary publication and for other outsiders, too, its doors remained bolted.

Here’s a link to the book:https://www.amazon.in/Broken-Home-Other-Stories/dp/B074FLYG3G