AGOMONI! Invoking the Goddess of Clay! How Kumartuli turned her abode

Subho Mahalaya

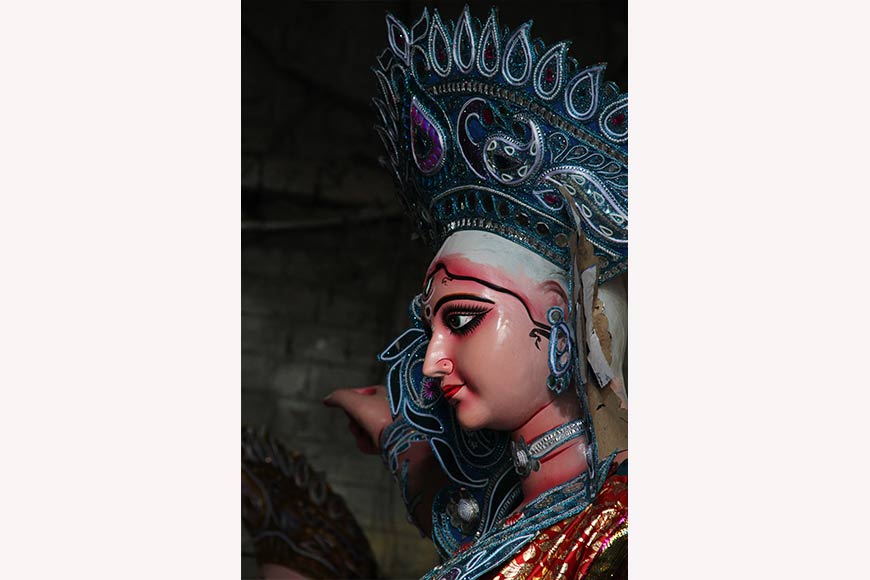

Curious faces of Durga stared peacefully at the play of clouds across the autumn sky. Arranged in a row on a muddy pavement, sloshed with a recent sharp shower, they were lying in abundance. The sun peeped, etching myriad shadows on their clayey smiles, so lively, yet with no trace of life. A violent eye of the demon, stared in stark reality on the opposite end. They were all left to dry, the Rain God proved to be an outrageous enemy to hundreds of artisans of Kumartuli. They were fervently praying to the same idols, made from their blood and sweat and expertise, to help them finish off those moulded arms in ten, fired from the clay of the Ganges. After all, they would take care of their hungry mouths the year round.

Kumartuli is not just a prevalent school of idol-making art of Bengal, rather it is a learning hub, that give birth to artisans, instead of ‘making’ them. Artisans who conceptualise and visualise life in a clay idol down generations and learn from peers, the art of idol making, instead of picking lessons from any modern art institution. Yet, these artisans know how to experiment every year with the Goddess of Clay.

Bengal had made a distinct place in the history of idol-making, since 8th century AD. During the reign of Pala and Sena dynasties, a new sculptural revolution started in this fertile land of the Ganges and reflected the richness of Indian sculptural traditions of ‘Devi Durga’ forms as seen in Mahaballipuram, Aihole and Ellora.

Three centuries ago, royal households of Bengal were primary patrons of Durga puja. It is believed King Kamsanarayan of Taherpur was the one to initiate Durga Puja almost 250 years ago, based on the classical canons suggested by the famous tantric, Ramesh Shastri. Since then, royal households worshipped Durga to show off their pomp and grandeur and to bridge a gap between the king and his subjects. Durga Puja thus represented the feeling of assimilation beyond any class divide.

From the kings, this tradition passed on to elite zamindars of Bengal who carried on the worship adhering to ancient mythological texts. Idol makers from Krishnanagar, Shantipur, and Nabadweep of Nadia district and Bikrampur of Dhaka, arrived in hordes and stayed at the royal household to give shape to idols of Devi Durga. Later, these artisans settled in the Kumartuli area of Kolkata and continued the ‘living tradition’ of idol-making.

From the kings, this tradition passed on to elite zamindars of Bengal who carried on the worship adhering to ancient mythological texts. Idol makers from Krishnanagar, Shantipur, and Nabadweep of Nadia district and Bikrampur of Dhaka, arrived in hordes and stayed at the royal household to give shape to idols of Devi Durga. Later, these artisans settled in the Kumartuli area of Kolkata and continued the ‘living tradition’ of idol-making.

With Durga Puja attaining popularity, potters were no more confined to the land of Nadia. Instead, Calcutta became an important centre for clay sculptures, second to Krishnanagar. The potters’ quarter in Calcutta at Kumartuli, was in the beginning an outpost of Krishnanagar, where sculptors worked during festive season and even brought their clay from Krishnanagar. Later, sculptors from other towns of Bengal moved to Calcutta in response to the ever-growing demand for idols.

Kumartuli came up almost 250 years ago, just after villages of Gondor, Satanity and Kolkata took shape. Clay-modellers from Nadia and Dhaka moved to this area on the northern fringes of present day Kolkata, by the banks of the Ganges. Courtly derives its name from tumour meaning clay-modellers and tulip meaning settlement. A parallel landscape of art activities was also flourishing around Kaalgat, a region adjacent to the Kali Temple in the city’s southern fringes. This was the place that gave birth to another form of Durra: Alight Pita Druga. Thus, began a new visual language amidst the city’s art arena.

Also read : Mahabharat’s Karna never performed Tarpan. Why?

In Changing Visions, Lasting Images: Calcutta Through 300 years, Pratapaditya Pal mentions: ‘A type of art flourished in Calcutta, as nowhere else on the subcontinent, for almost as long as the city has existed. It is that of unfired clay sculpture, consisting primarily of representations of Gods and Goddesses. Such sculptures are usually made for the autumnal celebration of Durra, but numerous other forms of deities are modelled throughout the year both for public and private worship. There is a saying in Bengali that in Bengal there are thirteen festivals in twelve months. All these religious occasions require images modelled with clay, cloth and bamboo, then painted, and finally clothed and ornamented. They are made by traditional artisans and craftsmen, who have for generations, settled in the city. Those who have seen hundreds of such images during a particular Puja, are aware of the astonishing variety of their forms. And those who have observed these festivals, must have noticed how their forms can change dramatically from year to year. Such changes not only reflect subtle comments on the prevailing aesthetic tastes, but occasionally on current political and social realities.’

True, the often anonymous creators of such transient clay sculptures were imaginative artists and revealed an intimate knowledge of their patrons’ tastes as well as the socio-economic conditions of the times. Potters in Bengal had many patrons. Any art needs an eye for appreciation and patronage to survive. Raja Krishnachandra of Krishnanagar was one such royal patron of Bengal’s idol making. Meanwhile, zamindars by then had earned riches by serving the British. To gain more attention from their British masters, they started celebrating Durga Puja with great pomp and show. Eventually, number of elite families worshipping Durga increased with the demand graph going higher. Thus, more artisans were brought in from Shantipur, Krishnanagar, Bikrampur and Faridpur. They stayed in wealthy households during festive seasons, to give shape to the deity.

But why did artisans settle in Kumartuli? Well, this area had a locational advantage for deriving raw materials to make idols. Supply of bamboo and clay was in abundance. Several zamindar families stayed nearby, such as Raja Naba Krishna Deb, Radhakanta Deb of Shova Bazaar, Dawn family of Jorasanko, Dutta family of Hatkhola, Khelat Ghosh’s family of Pathuriaghata Street and many more, who were benevolent patrons.