Alokranjan Dasgupta: The Eternal Baul of Words and Wanderings - GetBengal Story

"Bhogobaaner guptochor, mrityu eshe baandhuk ghor/ chhonde ami kobita chharbo na!"

Alokranjan Dasgupta seemed to have learned rhythm from the womb itself. He wanted to bind the whole world through the magic of words.

His childhood was spent in Santiniketan. With his classmate Amartya Sen, he published a magazine called Sphulingo (Spark). That’s where both his poetic spirit and love for Baul music began to appear. Since childhood, he had a deep attraction toward Baul songs. The poet loved folk music, Bhatiyali, and Santali tunes as well. Baul music was his life force — the seed of Baul spirit was planted in him from a very young age, and as he grew, that seed became a great tree.

The Baul essence that appears again and again in Alokranjan Dasgupta’s poetry is not just a metaphor — it’s an inseparable part of his poetic philosophy. His first poetry book, Joubonbaul (The Youthful Baul), announced this tendency right from its title. In this book, we find the drunken cremation man, the victory of life, garlands of beauty, and the grey rice fields of poverty. The poet sees Baul essence not merely as folk echoes, but as a blend of body philosophy, self-search, journey, and liberation.

In his poems, the body is seen as a secret library — where life and death play together. In one poem, he wrote, “Moron modmatal dom sobi koruk uposhom/ shmoshane, ami jeebon chharbo na” Such lines remind us of the Baul tradition of seeking God within the body.

His first poetry collection immediately drew attention among Bengali readers. Through his language, craft, and rhythm, Alokranjan created a new poetic world — filled with images of Bengal’s villages, Palestinian refugee camps, Santa Maria Hospital, and from Chhau to Kabuki. He never held back his pen, even when critics called his poems difficult.

Also read : Remembering poet Nishikanto Roychowdhury

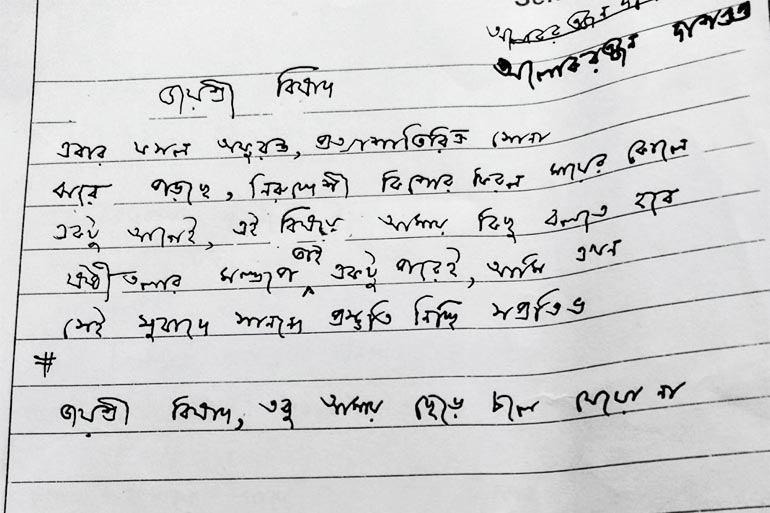

In the poem Bibhab from Joubonbaul, he wrote —

“Ekti matro Rakhal jaak, ek maath ekla pore thak, neerobe, ami e maath charbo na!”

And he didn’t. He even translated twelve songs of Purnadas Baul into German. Critics therefore called him the “Modern Baul” — the poet who brought Bengali folk philosophy into the sphere of world literature and created a new poetic language.

In his poetry, this Baul essence is a mix of roots and travel — rooted in Indian spirituality yet reaching out to the freedom of world literature. The first title of Joubonbaul was Poran Amar Sroter Diya (“Through the Stream of My Soul”), later changed to Joubonbaul. He dedicated this first book to Indira Devi Chaudhurani. Published on the last day of the Bengali year 1366 (1959), it remains a milestone in Bengali poetry — still resonating like an anklet’s sound after four decades.

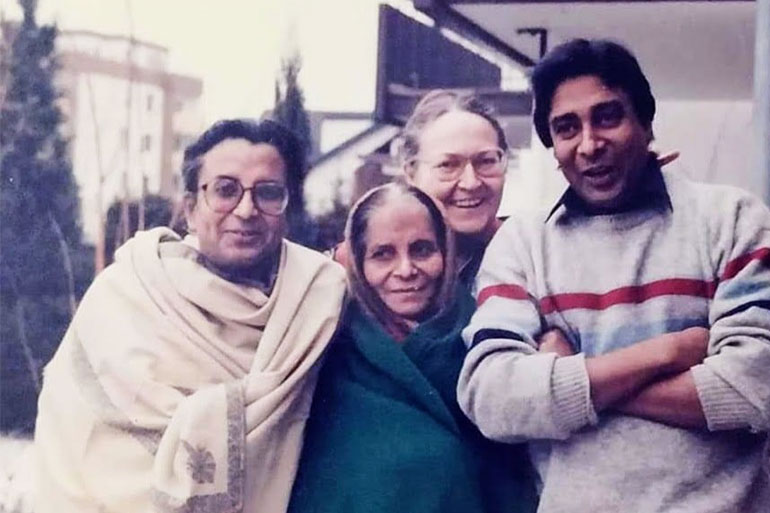

Alokranjan Dasgupta was born in 1933. He studied at St. Xavier’s College, Presidency College, and the University of Calcutta. From 1957, he began teaching Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University, and later in the Bengali Department. During his teaching career, he received a fellowship to Germany and eventually became a resident there. Yet he always carried the earthy smell of Bengal within him.

At sixteen, his poem was published in the magazine Desh. Even then, he knew his destiny — to walk forever beside Bengali poetry and its readers.

Alokranjan was a reader and translator of European modernism. He taught for many years at Heidelberg and translated German, Hungarian, and French poets into Bengali. As a result, his poetry became a unique fusion — a meeting point between the Baul spiritual tradition of Bengal and Western modern thought.

His rhythm was playful — stopping suddenly and flowing again like a Baul tune. He expressed deep philosophy and spirituality in simple yet mysterious language.

Among his poetry collections are Nishiddho Kojagori, Protidin Surjer Parbon, Roktakkto Jhorokha, Chhau Kabukir Mukhosh, Laghusangeet Bhorer Hawar Mukhe, Mormi Karat, Gilotiney Alpona, Nodi o Ratri Bonton Hoye Gele, Aayna Jokhon Nishwas Ney, Ek-ekti Upobhashay Brishti Pore, and Roktomegher Skandopuran.

He translated Sophocles’ Antigone, and poems by Holderlin, Heine, Rilke, Brecht — and even Surdas. He also translated many Bengali poems, essays, and songs into German. He received the Sahitya Akademi Award, Rabindra Award, and Germany’s Goethe Prize.

He had a wonderful sense of humor. Poet and researcher Dr. Rajatkanti Singha Chowdhury recalled that Alokranjan once said, “Can the people leaving a wedding feast really be called sufferers?” Once, while reading poetry at a private event, someone interrupted and said, “Alokda, please sit down.” The poet looked up and replied, “That sentence can mean something else too!” His wit and delivery were unforgettable, and people always gathered to hear him speak.

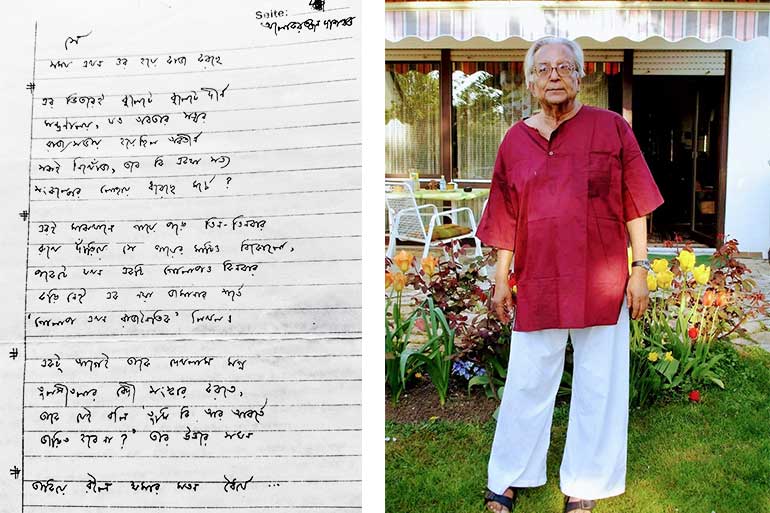

A funny thing happened on his 80th birthday. He was living in Hirschberg near Heidelberg. A delivery man brought a parcel — a bottle of wine. When Alokranjan opened the door, the man said, “Please call Mr. Alokranjan, I have a delivery for him.” The poet replied, “I’m the one.” The man didn’t believe him — “But you don’t look older than sixty!” The poet couldn’t convince him, and finally, the delivery man drank the wine himself!

Alokranjan remained forever young at heart. He once wrote,

“Chowranghee er footpath e/ amar shotabdir kaamdhenu / Dhele dichhe kaalo doodh seesa-ronga/ je khabe taar mrityu hobe/ je khabe n, taar murkhota bhalobashi na”

In 1992, he received the Sahitya Akademi Award for Mormi Karat. In his lifetime, he published about 20 books of poetry. He often compared his life to the song —

“Fagun hawaye hawaye korechi je daan, tomaar hawaye hawaye korechi je daan…”

He would softly sing these lines to himself.

Throughout his life, he remained deeply influenced by Santiniketan and Rabindranath Tagore. He once wrote, “I never call anyone mad.” In his middle years, he often searched for God, peace, and liberation — themes that appeared in his poetry.

His pen and mind often stirred with the movements of society, but he finally found peace in Baul songs and the wandering life. Though he lived abroad, he built bridges between two worlds — in life and in love.

That is the true success of a life — the fulfillment of his Baul devotion.

He has crossed the boundary of life, but as the Bauls believe — the body may die, the soul never does. Perhaps Alokranjan Dasgupta still walks somewhere — as the eternal “Joubonbaul”, singing, loving, and free.

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here.