Baroyari pujas and the age-old custom of ‘Pujor chanda’

In 1790 or thereabouts, 12 young men were denied entry to a private Durga Puja in Guptipara in Hooghly district, less than 100 km from Kolkata. Incensed and humiliated, they decided to start their own Puja. Only, it would not be a private event, as Durga Puja had hitherto been, but a public festival in which everyone could participate. This is a story told by multiple chroniclers of old Bengal, and the Puja thus instituted was to be called ‘baroyari’ (where ‘baro’ means twelve and ‘yar’ means friend). In its more expanded form, it was also to become a ‘sarbojanin’ (‘for all’ in Bengali) event. These two words have since become part and parcel of Durga Puja across Bengal.

Today, ‘baroyari’ and ‘sarbojanin’ pujas vastly outnumber private ones, but what were the earliest years like? In 1820, the ‘Friend of India’ published a feature on the baroyari Durga Puja and its growth over the past three decades. The article also mentioned that funds for the puja came from subscriptions raised from common people in Guptipara and surrounding villages. Thus began the practise of ‘pujor chanda’ (Puja subscriptions), a practise which, while it helped democratise the festival, also lay at the root of what was to become a social menace.

And it didn’t take too long either. Organisers of the first Puja at Guptipara managed to raise the then astronomical sum of Rs 7,000 from subscriptions alone, and neighbouring towns and villages enthusiastically jumped on to the bandwagon by hosting their own baroyari pujas. As the practise grew, so did the budget. At Chinsurah (also in Hooghly district), for instance, the budget was so large that there was plenty left over to stage lavish entertainments, good enough to draw the rich and famous from Calcutta.

Inevitably, the revenue potential, to put it politely, of public subscriptions soon became obvious to many. In his book ‘Glimpses of Old Calcutta (1836-1850) Ranabir Roy Choudhury writes that in February of 184o, The Calcutta Courier reported how “young men belonging to the family of the Saborno Chowdries of Bihala of Zilla 24-Parganas” used the baroyari puja as an excuse to stop passersby, particularly if they were in palanquins, and demand money from them. Women in particular seemed more liable to such extortion, and were even reportedly forced to donate clothes or jewellery if they weren’t carrying any money.

Because the Saborno Roychowdhurys were wealthy enough to organise a baroyari puja without having to resort to such unfair practises, the story may not necessarily be entirely accurate, but it does prove two things. One, the baroyari puja had reached the threshold of Calcutta, subscriptions and all. And two, the custom of collecting money from the public to finance big-budget pujas was clearly thriving, enough for the authorities to take steps to regulate it, because the above report also states that in 1840, the magistrate of 24 Parganas was forced to travel incognito in a palanquin to catch the perpetrators redhanded.

When it came to Calcutta proper, a trader called Shib Krishna Dawn took it upon himself to raise subscriptions from other traders and businessmen for one of the city’s earliest baroyari pujas, and this became a year-long drive, with the monies being deposited in the custody of a designated individual who was to function as a sort of secretary. Easy to spot the beginnings of modern Puja committees here.

Kali Prasanna Singha’s legendary work ‘Hutom Pyanchar Nasksha’ (published 1861) is a rich source of anecdotes about the fiercely competitive nature of baroyari pujas since almost their inception. The book is freely available in Bengali as well as English.

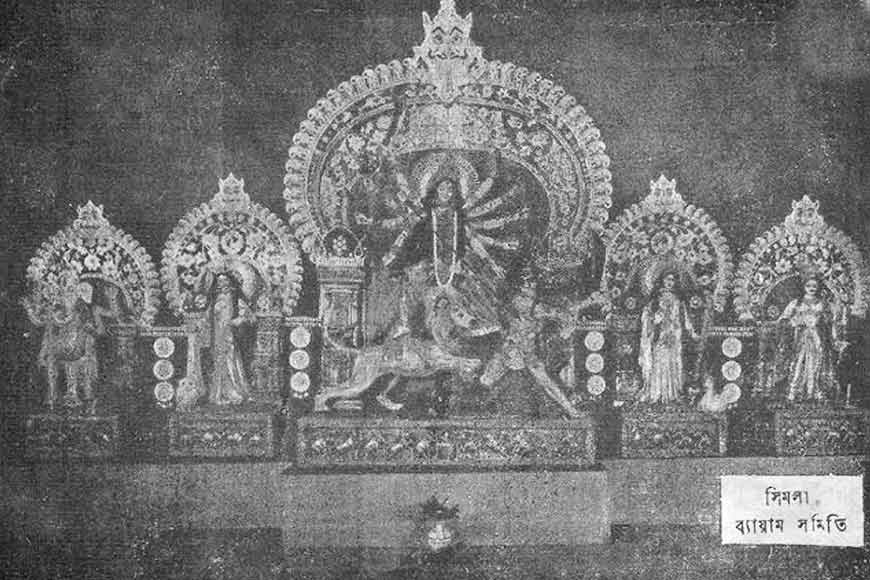

Recorded history indicates that Calcutta was instrumental in expanding the concept of baroyari and making it sarbojanin. The first such effort was the Durga Puja held in 1910 on Balaram Bose Ghat Road in Bhawanipur’s Patuapara area, organised by Sanatan Dharmotsahini Sabha. In the following decade, more such pujas came up in north Calcutta, too, including Simla Byayam Samity and Bagbazar Sarbojanin. And Kumortuli followed in 1933. But that is a story for another day.

Information courtesy: Durga Puja, Celebrating the Goddess: Then and Now by Sudeshna Banerjee