Between Love and Wounds: Arundhati Roy’s Story of a Mother - GetBengal Story

Around 2008, Alice Walker’s daughter Rebecca Walker wrote: “Strangely, my mother thought of herself as very maternal. She would travel the world campaigning for women’s rights, portraying them as oppressed. She would set up organizations for abandoned girls in Africa—presenting herself as the very embodiment of motherhood.”

Alice Walker was not only a feminist activist but also the author of The Color Purple, one of the central books of second-wave feminism. Rebecca’s essay was titled “How My Mother’s Fanatical Views Tore Us Apart.”

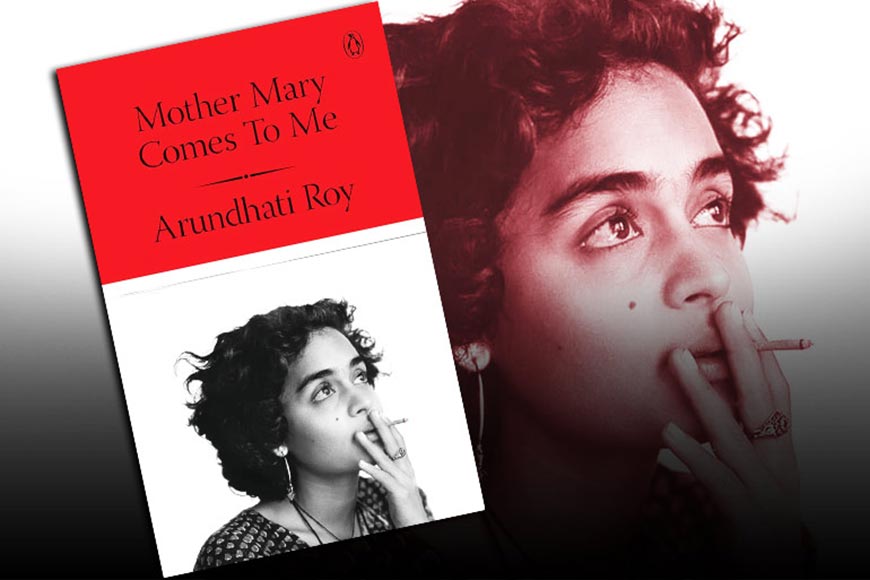

That same year, 2025, came another book: Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me. Roy, the Booker-winning author of The God of Small Things, never settled into a quiet literary life after her success.

In 2025, Erica Jong’s daughter Molly Jong-Fast wrote something strikingly similar: “Funny thing—when I was little, my mother used to say she was such a great mom. Then when I got older, she would claim she was deliberately trying to raise me with ‘benign neglect.’ As if that was a well-thought-out parenting philosophy. One day, as she kept repeating this (knowing full well she had been a terrible mother), I snapped. I told her, ‘Neglect is neglect’. Call it what it is. Don’t dress it up as “benign.” Stop saying that.’ She never said it again.”

Erica Jong’s feminist novel Fear of Flying had once created a storm. Molly Jong-Fast herself is a writer too. These words appear in her book How to Lose a Mother.

That same year, 2025, came another book: Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me. Roy, the Booker-winning author of The God of Small Things, never settled into a quiet literary life after her success. Her pen has stood with the Narmada Bachao Andolan, against corporate land grabs, against AFSPA in Kashmir. In Mother Mary Comes to Me, she frames her own tumultuous relationship with her mother, Mary Roy, against the backdrop of the Naxalite movement, the Emergency, and the rise of today’s fascist aggression. The Narmada valley, Dantewada, Kashmir—all reappear here, though nothing new is said beyond what her earlier political essays already contained.

It takes courage to confront the state. But it takes just as much courage to fling open the doors of one’s private life. Feminism has long said that the personal is political. Still, writing in a detached, theoretical tone about private wounds in the third person is one thing; tearing down that curtain and laying bare the raw first-person hurt is another. That is the leap Roy makes in Mother Mary Comes to Me.

And her book stands apart from Rebecca Walker’s or Molly Jong-Fast’s. Arundhati writes less as a daughter and more as a fellow woman. The pen she picks up for this autobiographical-maternal narrative is the pen of a novelist. Fiction and non-fiction blur. She wants them to. As she puts it: “A novel is that strange hazy thing, not wholly mine, yet something I feel as mine. Let this book be read as a novel. It claims nothing more.”

Like The God of Small Things, this autobiographical work is poetic, ironic, and laced with humor. Just as Ammu in God of Small Things was divorced, so was Mary Roy. Both had married young simply to escape suffocating homes—like so many women who marry the first man who offers them an escape from abuse and repression. Mary Roy’s father, a civil servant, used to beat his wife, son, and daughter without distinction. Mary married and moved to a tea estate in Assam, only to realize her husband Mickey Roy was an addict. Within three years she was mother of two, unwilling to live in remote forests raising children alone. She moved from Assam to Calcutta and finally back to her family’s abandoned estate in Ooty. But her authoritarian mother—whose beloved violin had once been smashed by her violent husband—sided with her son instead, traveling down from Kerala to Ooty to try and evict Mary and her children. By sheer chance, Kerala’s Syrian Christian inheritance law did not apply in Tamil Nadu, sparing them for the time being. But eventually, humiliated and worn down, Mary had to leave Ooty and return to Kerala.

She lost her teaching job to asthma. She endured years of dependency on reluctant relatives. Her later bitterness may not be excusable, but it is understandable once one sees its roots. A woman who dragged her two children through the night to a lawyer’s home, fearing homelessness—her trauma explains her later harshness. Through Arundhati’s eyes, we see how patriarchal violence flows down generations. Not just men, but women, too, become carriers of that baton. The grandmother who suffered domestic abuse could not support her daughter; the mother who once ousted herself turned her rage against her own children.

Roy does not paint the men as villains either—her brother Isaac, her father Mickey, or her Marxist uncle. As a novelist, she probes deeper. She records the petty squabbles over money in so-called cosmopolitan families, the uncle who preached Marxism but cared about inheritance, the same uncle who also introduced her to the Meenachil river and to humor, who memorized her books cover to cover. Mickey Roy, “the Nothing Man,” emerges as a strangely charming supporting character. Even failed men, in her writing, are given color, wit, texture.

Mary Roy, before her marriage, had trained as a teacher and later founded a school in the small town of Kottayam. She famously went to the Supreme Court in 1986 to win inheritance rights for Syrian Christian women. As a principal, she was radical. When she caught two boys harassing girls, she made them fetch her bra from her hostel room and held it up before them: “This is a bra. All women wear it. Your mother wears it. Your sisters will soon wear it. If you’re so excited by it, you can keep it.” She gave girls courage to break out of darkness, and saved boys from becoming patriarchal bullies.

And yet, the same Mary Roy called her teenage son a “male chauvinist pig” and beat him mercilessly for getting average grades. To Arundhati she would say, "If I were as dumb and ugly as you, I would kill myself." He never failed to mention that although she was brilliant, he nonetheless continued to humiliate her brother. Arundhati recounts, "From then on, whenever I was praised I felt someone else, someone quiet, in another room was being denied." Mary hurled cruel insults at servants, at her daughter, at her daughter’s first love, calling her a whore, reminding her she was an unwanted child. She even shot her dog Dido—who became pregnant after mating with a mongrel—calling it an “honor killing.”

At times Mary seems insane. But Arundhati reminds us: countless Indian women, driven nearly mad by domestic violence, exist in similar ways. Their perfect maternal façades hide brutal child abuse. When Mary eventually won the legal battle to evict her own brother and mother from their Kerala house, it was with the same ruthless insistence that had kept her alive.

She lost her teaching job to asthma. She endured years of dependency on reluctant relatives. Her later bitterness may not be excusable, but it is understandable once one sees its roots.

At sixteen, Arundhati left for Delhi to study architecture. “Not because I didn’t love my mother, but so that I could go on loving her.” Architecture fascinated her partly because it was her mother’s dream field, the work of Laurie Baker. Mary pushed her into writing too—urging her to “free write,” to put anything on the page. Mary gave her Shakespeare, Kipling, world literature, communism, Vietnam. She inaugurated The God of Small Things at her own school, inviting the daring poet Kamala Das as chief guest. But once her daughter began to outshine her, Mary grew jealous, disrupting her readings.

This story is as much Mary Roy’s as Arundhati’s. The years they spent apart were Arundhati’s years of self-discovery. Friends, lovers, comrades fill the pages—Carlos, Pradip Kishen, Sanjay Kak, Golak, her first love JS. Respectful portraits, alongside encounters with predatory men knocking on her door at night. Her humour always saves her. She calls one would-be rapist “a hideous tattoo come alive.”

Tellingly, Arundhati calls her mother not “Ma” but “Mrs. Roy.” As a person, as a woman, she earns empathy. But as a mother, she inflicted irreparable wounds. Children of such mothers often drown in whirlpools, or smash against rocks while fleeing. Arundhati survived through sheer individuality. But her loveless childhood left her “alone in a crowd,” no matter how many admirers or lovers surrounded her.

James Joyce had written A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. This book becomes A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman. It tells the story of Arundhati finding her own language: “I had to stalk a language like prey. Drag it out, eat it raw, a living striped beast waiting for me.” Each time she narrates her mother’s violence, she also provides the cause. That may seem like bias toward her mother. But it is also the novelist’s habit of probing deeper into character.

The book’s title comes from the Beatles: “When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me, speaking words of wisdom: Let it be.” Arundhati, too, has learned to say “let it be.” But her own Mother Mary was no saintly figure. And yet, her mother’s stubborn defiance—against society, patriarchy, collectors, courts—coursed into her. It made her fearless before governments and judges. The barbs left by her mother did not just wound her; they hardened her, sharpened her, and made her a writer.

Two moments in the book are deeply moving. One: after reading The God of Small Things, Mary Roy asked, “You were so little—did you really remember all that?” Arundhati said, “It’s fiction. I made it up.” Mary replied, “No, you didn’t.” And turned away, her face bathed in the dying light against a yellow curtain.

The other: late in life, the proud Mary Roy—who had never hugged her children—could no longer type. Through an assistant, she texted her daughter a simple message: she loved her very much. Written in cold, utilitarian words, because she didn’t know the language of tenderness. But the ice cracked, and something began to flow.

That feminist organizers, teachers, and writers can fail so bitterly in personal motherhood is not a new revelation. Feminism never asked women to put children before themselves. It only spoke of the toll childrearing takes on women. But when feminist mothers and non-feminist mothers alike are equally ruthless toward their children, equally passing down the burden of their own trauma—then one must admit feminism hasn’t solved this riddle. Why? Perhaps because some people simply do not know how to love, having never been loved themselves.

By writing Mother Mary Comes to Me, Arundhati runs her fingers through her mother’s unquiet, rough hair. If only all Mary Roys, feminist or not, could have someone to stroke their heads endlessly—perhaps one day, every buried spring would begin to flow.

Note: Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, please click here