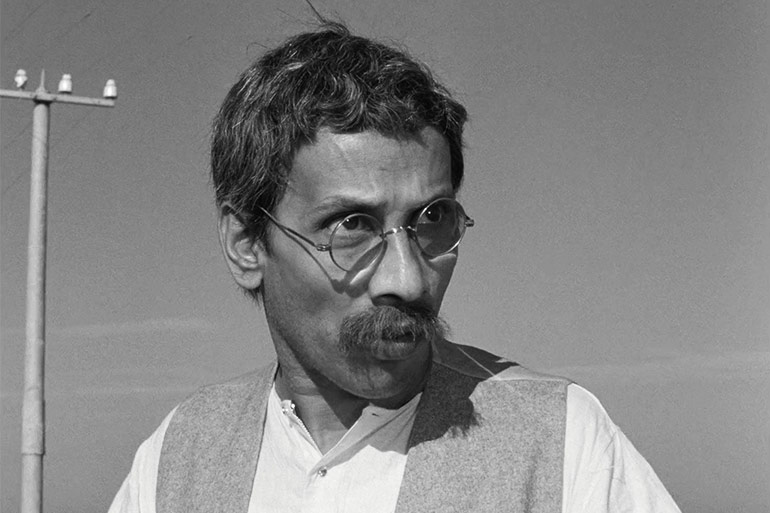

Bijon Bhattacharya and his struggle for theatrical identity – GetBengal story

OThere is a strange kind of sieve of acceptance and rejection within the world of theatre. According to me, "Bengali theatre," means the people associated with theatre in Bengal. Bijon Bhattacharya has been respectfully set aside, kept outside our familiar and practiced circles. The one erudite and scholarly individual who has consistently used his pen to prove Bijon Bhattacharya's uniqueness and excellence is Shamik Bandopadhyay.

Let me say the hard truth — Bijonbabu's work did not quite influence or inspire us in that way.

His thematic ideas do not align with his ideas of execution. New and unconventional plays presented within a decaying and old-fashioned stage setup. Even in the direction of Nabanna, we see a crude imitation of Western theatre’s naturalism.

The Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) staged Agun in 1943, Jabanbandi and Nabanna in 1944. Nabanna was performed for seven days at Srirangam, and later at various venues and conferences — staged at least forty times. His play Jiyonkanya, written in 1945, was staged only once at Rangmahal in 1950. He himself admitted, “The production wasn’t good, otherwise I would’ve pursued that form further.”

His one-act play Morachand, written twenty years earlier, was given full form in 1946. It continued to be performed until 1952. There’s no record of a staging of Abarodh, written in 1947. The first production by Calcutta Theatre was Kalank (1951). There’s no record of the staging of Jananeta (1951) or Jatugriha (1962) either.

Rudraprasad Sengupta refers to him as a “rugged tree of talent left untended.” First IPTA, then his own groups — Calcutta Theatre and Kabach-Kundal. In the first, too many leaders spoiled the broth; as for the latter two, it can be said that he lacked the organizational skill or drive needed to form and sustain a theatre group actively. From that arose a certain disorderliness. When an organisation is disorganised, that reflects in creative work as well.

Thus, however unfortunate and harmful it may be, Bijonbabu’s productions could not leave much of an impression on the minds or thinking of theatre workers of that time — unlike his individual acting brilliance in films like Meghe Dhaka Tara, Subarnalata, or Padatik, or in Utpal Dutt’s stage production of Titas Ekti Nadir Naam.

His thematic concerns did not match his executional thinking. Bold, unconventional ideas in a dilapidated, outdated stage system! Even in Nabanna’s direction, one can feel the crude mimicry of Western naturalism:

"Nepothye ekta boro gachh bhenge porar shobdo, mor mor moraat. Kancha pata pallob, daal shob chhire eshe pore uthone. Dochhalakhana nordte thake ghanoghan, je kono muhurte bhege porte pare ar ki. ...Dekhte dekhte dochhalakhana bhege pore prodhaner."

("A loud cracking sound of a tree falling offstage…Raw leaves, branches, all fall into the courtyard. The thatched house begins to shake again and again, as if it might collapse any moment... Slowly, the house collapses over the protagonist.")

All this is a third-rate imitation of the professional proscenium theatre!

Perhaps Rudraprasad was right when he said, Bijon Bhattacharya was “god-like in talent, and perhaps childlike in disorder.”

Note : Translated by Debamita Ghosh Sarkar

To read the original Bengali article, please click here :