Mantu Hait: The lawyer who gave Kolkata a forest– GetBengal story

OWhen we’re young, we’re taught that planting trees is important because they give us oxygen. However, no one tells us that trees are essential for many other reasons as well. It's not just about planting — protecting big, grown trees is just as important.

Children are rarely told how much damage has already been done to the environment — and that simply planting new trees won’t fix everything. According to Mantu Hait, a lawyer by profession, “Environmental education and awareness about biodiversity should begin in childhood.”

He adds, “As I grew older, I realised that planting trees isn’t enough — they also need proper care and protection. I believe this responsibility lies not just with students or researchers, but with all of us in society.”

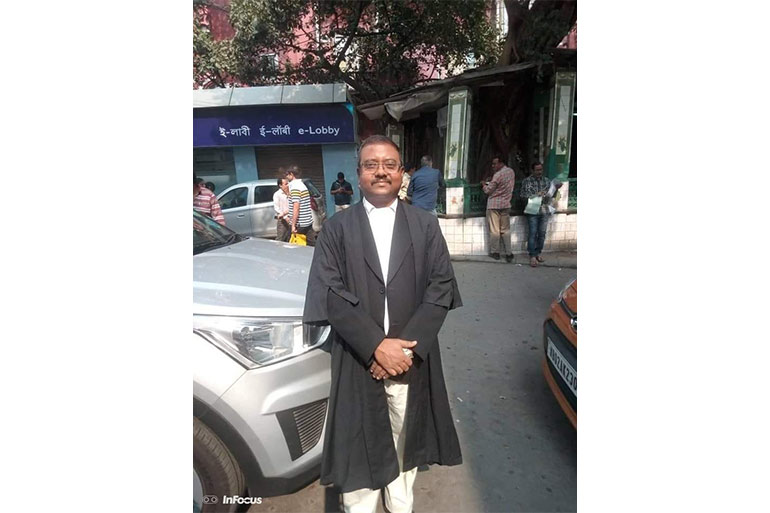

Though a lawyer by profession, Mantu Hait — a resident of Chetla, Kolkata — is a passionate nature lover and environmentalist. Over the past few years, he has become known as the “Forest Man of the City,” “Kolkata’s Green Man,” or simply, the “Tree Man.”

One day, Mantu Babu decided to plant trees on a vacant stretch of land between Majherhat and New Alipore railway stations — an abandoned space that had turned into a garbage dump over the years. Legally, the land belonged to the Kolkata Port Trust, and planting anything there without permission would technically be illegal.

But that didn’t stop him. He made up his mind to go ahead and plant trees, using guerrilla style. Without waiting for approvals. Because for him, saving nature couldn't wait.

He collected seeds from various places — jamun and boxwood from the Alipore Court premises, along with ashoka, jackfruit, mango, tamarind, guava, and many more. He scattered them across the dry, neglected land and also planted a few saplings himself.

Over time, the once-barren stretch — nearly a kilometre long — began to turn lush with around 20,000 trees. The area slowly transformed into a green oasis in the heart of Kolkata. Some began calling it “Montu’s Garden,” while others lovingly named it the “Chetla Forest.”

Birds, insects, and small animals of different species started making it their home. Even after many trees were damaged during Cyclone Amphan, Mantu Hait didn’t give up. He continues to care for and revive the green space.

This is Mantu Hait’s way of practicing guerrilla gardening. For him, protecting greenery isn’t just a nice thought; it’s a personal mission. Since his school days, Mantu had quietly made a promise to himself: he would do something meaningful for the environment. And that promise led him to choose this path.

But guerrilla gardening didn’t just give him one way forward — it opened up many new possibilities, each rooted in care, courage, and a deep love for nature.

This is how Mantu Hait embraces guerrilla gardening. For him, protecting green spaces isn’t just a good idea — it’s a lifelong commitment.

Back in his school days, he made a quiet vow to do something meaningful for the environment. That silent promise shaped his journey and led him down this path.

But guerrilla gardening became more than just an act of planting — it opened doors to many new possibilities, all grounded in care, courage, and an unwavering love for nature.

Most major educational or research institutions in the country work only with their own students or researchers. But what about those outside these circles — the curious learners, the environment enthusiasts, the common people who want to know more about nature?

Why should they be left behind when it comes to understanding the natural world deeply?

Driven by these questions, Mantu Hait took matters into his own hands. He began purchasing land, first near his ancestral home in Amta, Howrah, and later, around 8 bighas on Bali Island in the Sundarbans.

There, he established the Sundarban Delta Eco Tourism Cottage & Nature Study Centre, a space built for learning, exploring, and reconnecting with nature.

Mantu Babu has already set up Nature Study Centres in five different locations. West Bengal is home to five distinct climatic zones, and he has carefully planned each centre around these unique ecosystems.

His vision is to create study hubs based on the natural diversity of these regions — from the mangrove-rich saline areas and coastal sand dunes, to floodplains, the Himalayan foothills, and the rugged terrain of Rarh Bengal.

Each centre is designed not just as a learning space, but as a living classroom where people can truly connect with the land, climate, and biodiversity around them.

Mantu Babu says, “Back in school, I used to bring saplings from the Alipore Forest Department, four or five at a time, and plant them around my neighbourhood. Today, many of those trees have grown into massive giants. But later, I learned that some of those species weren’t native to India. In fact, they weren’t even environment-friendly; they absorbed excessive water from the soil.”

“I didn’t know that back then — and I know many others still don’t. There’s a serious lack of awareness and understanding when it comes to nature. That’s when I realised we need to change this. Towards the late ’90s, while I was finishing my graduation, I began mentally preparing to work in this direction. In 2005–06, after entering the legal profession, I bought my first plot of land in Amta, Howrah, for the Nature Study Centre. Due to some legal complications, I couldn’t buy the entire plot, so I purchased the rest later in Raspur. That was followed by the land in the Sundarbans. From 2010, I slowly started shaping the space the way I had envisioned. By 2012–13, the work was complete.”

With a hint of sadness in his voice, he says, there are many bright students in Bengal, and across India, who want to study nature seriously. But they often give up or fail simply because they lack access to technical knowledge. Sadly, very few people want to step in and support them. Meanwhile, people from outside the country come here and do just that, and they succeed.

According to Montubabu, no chemicals are allowed anywhere near his Nature Study Centre. His Sundarban Delta Cottage and Nature Study Centre are completely unique—both geographically and botanically. The place brings together climate, environment, geography, history, and science in a way that creates a rich learning experience. Alongside nature studies, he has also introduced eco-tourism here.

Apart from the guests staying at the Delta Cottage, students and researchers from various schools and colleges also visit the centre on educational excursions and benefit greatly. He said, “Many families come here to spend time together. I believe children should grow up with a natural awareness and sensitivity towards the environment, and that journey should start early. To support this goal, he has set up small laboratories focused on dragonflies (different species), butterflies, birds, and fish at the Sundarban Nature Study Centre. There are two centres with labs—one in Amtala and the other in the Sundarbans, both chosen for their proximity to Kolkata, making travel easier. The Geological Survey of India’s (GSI) Kolkata Director, Kasturi Chakraborty, also visited the Delta Cottage to study the unique geology of the Sundarban delta. Her visit marked the official inauguration of the Geological Laboratory at the Nature Study Centre. Nature Study Centres have also been established in Bakkhali and Buxa, though they do not have labs. A location is still being scouted in Purulia for a future centre.

He shared, “The Nature Study Centre in Amta, Howrah, is located in the middle of a natural basin-like area, surrounded by nearly 10,000 acres of land. We’ve taken around 8 bighas of land here, with a canal running through it. Thanks to the natural water retention system, the area stays filled with water throughout the year. Fish breed across this vast stretch of land, and from the end of the monsoon onwards, local farmers collect fish almost year-round. The local panchayat now leases these water bodies to traditional fishermen. This has not only benefited the local fishing community but also ensured that a variety of indigenous fish reach nearby markets, including Kolkata. It helps meet nutritional needs while preserving native fish species.”

He further added, “PhD researchers frequently visit the site. Schools and colleges organise camps here to study nature in an open, clean-water environment. Tent accommodations are available for those who wish to stay overnight. My ancestral home is just two kilometres from here. If needed, I arrange stays there as well. I want nature to stay as it is. I’ll never allow construction on this land in Amta. Many people have money—they could buy land and start building on it. But this land must remain untouched, just the way nature intended.”

Montubabu and his team have set up a Nature Study Centre in a coastal area, where a trained marine guide is available to help visitors understand the local marine ecosystem. In Buxa, their camps are held near the Buxa Tiger Reserve, which, apart from tigers, is rich in wildlife, birds, and diverse plant species. During these camps, they make a conscious effort to showcase the biodiversity in detail. Groups of people regularly join these guided camps.

They are slowly starting similar activities in Purulia as well. Since both Sundarbans and Buxa offer a wide range of nature-learning opportunities, camps and excursions are organised more frequently in these two regions.

Montu Hait mentioned that several institutions have already participated in these educational trips—including Bangabasi College, Derozio College from Salt Lake, Siddheshwari College from Bagnan, Howrah, and RBC College from Naihati.

Montubabu is no longer alone in his mission. Many people who have seen his work up close have been deeply inspired—some have even taken up individual initiatives like guerrilla gardening or other environmental efforts. He now collaborates with several NGOs and voluntary organisations to carry out various programs and projects.

He chooses not to take any government aid, as he wants to work independently, without having to compromise on his values or methods. However, he is firm about one thing: if anyone harms nature in any way during this journey, he will not hesitate to seek administrative or legal support when necessary.

Montubabu shared a few more important thoughts. According to him, large-scale afforestation may not be practical in urban areas, but that doesn’t mean cities can’t contribute. “If there’s an empty or unused plot nearby, a small garden at home, or even a rooftop—use it to create an urban forest,” he said. He believes this idea needs to be spread as widely as possible.

Just like we have microfinance, he proposes the concept of micro urban forestation, which is crucial for preserving biodiversity. Even a small patch of green can release oxygen over a surprisingly wide area. If more people take this up, it can naturally develop into a sustainable system.

But not just any trees—Montubabu emphasises the importance of planting native species. Protecting birds, small animals, and insects are equally essential to maintaining ecological balance. “Birds won’t go hungry; they’ll eat the fruits and disperse seeds. Insects play a key role in pollination—without them, how will new life grow? Not all bugs are harmful. We need to get rid of irrational fears and stop harming them.”

At the root of it all, Montubabu’s Nature Study Centre is not just about learning facts—it’s about changing mindsets and reconnecting with nature from the ground up.

In the Sundarbans, Montubabu has created a beautiful Butterfly Garden spread across nearly two bighas of land, which is best enjoyed between the monsoon and early autumn. While butterfly gardens are common across India, including West Bengal, what makes this initiative truly unique is the creation of the country’s first-ever man-made Dragonfly Pond.

This pioneering effort was made possible with the help of his close friend, Professor Prosenjit Dan—an Assistant Professor of Zoology at Shyampur Siddheshwari College, and his students. Prof. Dan is also a dragonfly specialist and has been actively involved in this and several other collaborative environmental projects with Montubabu. Together, they are setting a new benchmark in biodiversity education and conservation.

Montubabu has dedicated his Butterfly Garden and Dragonfly Pond to fellow nature lover Shubhankar Patra of Sunday Watch, as a tribute to his passion for the environment.

Dragonfly ponds are more commonly found in countries like Japan and China, where people even buy dragonfly larvae to release into their own ponds or small water bodies. This helps sustain the natural lifecycle of dragonflies. Interestingly, dragonflies also play an important role in controlling mosquito populations, making them natural allies in maintaining ecological health.

Montubabu raises a pressing concern: Why are dragonflies disappearing from our cities? The answer lies in the vanishing water bodies. Dragonflies are born in water—they lay eggs, grow as larvae, and emerge from ponds and wetlands. As urban water sources shrink, so does their habitat.

Through his initiative, Montubabu not only restores this lost balance but also spreads awareness about the quiet, powerful role creatures like dragonflies play in our ecosystem.

Montubabu says, "One thing I’ve truly understood over the years is that nature should be left to be itself. That alone does half the work. You don’t always need to make a grand effort. To be a nature lover or a social worker, you don’t have to always fight loud battles. But at the same time, sitting in air-conditioned rooms and only discussing won’t help either. Real change happens when you step out and work on the ground.

Translated by Sabana Yasmin

To read the original Bengali article, please click here: