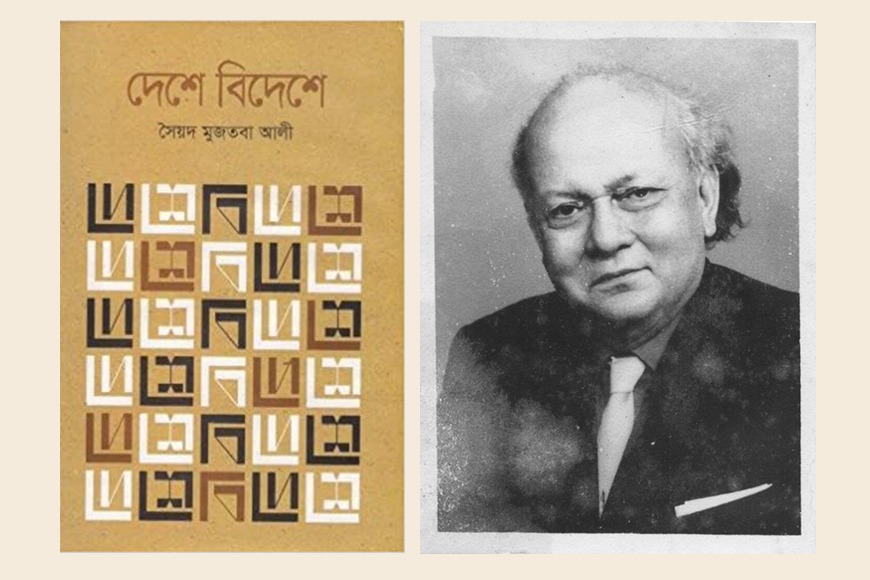

Mujtaba Ali’s ‘Deshe Bideshe’ describes life in Kabul as never seen before

Afghanistan’s troubled history has been stained with bloodbath, but this is again a nation that had caught the attention of legendary Bengali author Syed Mujtaba Ali, who saw this country from a different perspective. An intrepid traveller and a true cosmopolitan, the legendary Bengali author, journalist, academician, scholar and linguist Syed Mujtaba Ali spent a year-and-a-half teaching in Kabul from 1927 to 1929. Drawing on this experience, he later wrote ‘Deshe Bideshe’ which was published in 1948.

Ali went to Kabul to serve as a Professor in the newly-reformed education system under King Amanullah and lived there as a part of a small Western community of professors and diplomats from Russia, India, France, Italy and Germany. Ali’s book, therefore, can be read as a document exploring a ‘contact zone’ revealing a half-forgotten episode of Afghan history and nationalism with the British and the Russians playing political games, scarcely disguising their imperialistic ambitions. The Civil war and siege of Kabul that had forced Ali to return had ended long ago with the killing of Habibullah Kalakani or Bacha-ye Saqao but the country’s scarcely regained political calm was shattered again due to the assassination of King Nadir Shah in 1933.

Mujtaba Ali was concerned at the fragile political condition of the Afghan nation and was pained by the defeat of King Amanullah and the consequent retreat of his modernist reforms.

Mujtaba Ali’s visit to Afghanistan had coincided with the last couple of years of King Amanullah’s reign when most of his reformist policies were already underway. Amanullah’s reformist zeal had ushered in a decade of great social transformation. He had undertaken to change the traditional ways of Afghanistan to suit the modern age. A lot of the conversations and discussions in the text converge on the effect of the King’s reforms and their effects on Afghan society as a whole and their repercussions on his rule. Deshe Bideshe drafts Ali’s admiration for Amanullah because of the latter’s valiant campaign against the British in the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919 and his establishment of full sovereignty including the country’s right to conduct its own foreign affairs. However, Amanullah’s penchant for European norms of educational and social reform did not go down well with the conservative forces. Many Afghans were critical of Amanullah’s policies and held him responsible for the frequent rebellions by various Afghan tribes across the country against him.

Ali was cerebrally aroused to explore the Afghan society of that time and with his impressive language skills, he had access to a cross-section of Kabul’s population, whose ideas and experiences he chronicled with a keen eye and a wicked sense of humour. His account provides a fascinating first-hand insight into events at a critical point in Afghanistan’s history, when the reformist King Amanullah tried to steer his country towards modernity and he was branded a ‘kafir.’ Amanullah was later overthrown by the bandit leader Bacha-e-Saqao.

‘Deshe Bideshe’ is the only published eyewitness account of that tumultuous period by a non-Afghan, brought to life by the contact that Ali enjoyed with a colourful cast of characters at all levels of society—from the garrulous Pathan Dost Muhammed and the gentle Russian giant Bolshov, to his servant, Abdur Rahman and his partner in tennis, the Crown Prince Enayatullah.

Mujtaba Ali glorified the spirit of nationalism in Afghanistan. He wrote enthusiastically about Afghanistan as an independent country and felt a tinge of sorrow for being a representative of a colonised nation --- India under the British rule.

Mujtaba Ali was concerned at the fragile political condition of the Afghan nation and was pained by the defeat of King Amanullah and the consequent retreat of his modernist reforms. His experience of colonialism in his motherland coupled with his faith in a fraternal bond with fellow Orientals gave him a distinct perspective on Afghanistan.

The Western intervention into Afghanistan started with the British in 1838, but when Ali visited Afghanistan, it was still a country that hoped for a stable future. Perhaps one of the reasons for the contemporary relevance of Mujtaba Ali’s book today is its portrayal of a different Afghanistan. Ali does not have the European traveller’s superior air when writing about Afghans. In fact, he is empathetic when he portrays Afghans, their habits, character and customs and his description is mixed with witty comparisons and associations between languages, customs and religions.

The ordinary Afghan, according to the author’s Afghan friends is no doubt violent, but not violent by nature: it is rather the lack of fertile lands, lack of other opportunities and their indisposition for business that compels them to opt for the army or recourse to robbery. The Afghan is intensely vengeful, especially in matters of honour, and he values his gun above anything else. On the other hand, he absolutely loves companionship and freewheeling conversation full of stories and anecdotes. The independent spirit of the Afghans impressed the author immensely. The Afghan is proud, brave and belligerent, but is also very much humane in his kindness, generosity and simplicity. In Ali’s account, the descriptions of the Afghan character are offered by Afghans themselves on various occasions, revealing their open, unreserved natures.

Also read : 'Nilkantha Pakhir Khonje' and the circle of life

Mujtaba Ali’s experience of colonialism in India combined with his profound sense of history makes him uniquely capable of providing a glimpse of Afghanistan during a period of social and cultural transformation. The period of Ali’s visit coincided with the historical epoch known as the ‘great game’, when the British and the Russians vied for control of Afghan territory and politics. The British wanted to use Afghanistan as a buffer state to protect British interests in the Indian subcontinent from a presumed Russian invasion. Ali’s account ended abruptly as he had to leave Afghanistan following the rebellion of tribals led by Bacha-e Saqao in 1928, the ensuing Afghan civil war and the end of Amanullah’s reign.

Ali vividly wrote about the days of suffering he witnessed in Kabul, especially his own experience of near starvation during the time. He also regretted his inability to meet the Afghans living in the villages, the tribal population, and losing an opportunity to understand their practices and economy. He scathingly criticized the utter poverty and lack of economic resources of the villages, the stiff taxation policies and the resultant vicious cycle of economic backwardness that fuels tribal rebellions in different parts of the country.

Ali went to Kabul to serve as a Professor in the newly-reformed education system under King Amanullah and lived there as a part of a small Western community of professors and diplomats from Russia, India, France, Italy and Germany.

Mujtaba Ali glorified the spirit of nationalism in Afghanistan. He wrote enthusiastically about Afghanistan as an independent country and felt a tinge of sorrow for being a representative of a colonised nation --- India under the British rule. For Ali, Afghanistan was a mirror, where he could see a reflection of his own thoughts and feelings for India. Afghanistan and its resistance to colonialism became a comparative framework for India.

Ali’s hostility towards the British was evident in his reflections on Afghanistan’s recent history, especially in his comments about the third Afghan war. Kipling’s phrase, “the white man’s burden” got a wholly new interpretation from his fellow traveller, a man from Kabul whom he befriended during his travel through the Khyber Pass. According to this man, the phrase refers to the unselfish efforts of the white imperial race to eternally prolong the institution of starvation deaths in the poor Orient. And since the poor people of Afghanistan prefer to carry their own burden, passports are denied to the ‘deeply religious’ Christian missionaries who are over eager to carry the ‘burden’.

Ali, in his characteristic humour, compared his newly-received wisdom to the gospel of Mark and Mathew! He compares the plundering British to some everlasting Timur or Nader Shah, who ravaged the subsequent history of India and Afghanistan. Quite significantly, he invokes the half-forgotten history of King Mahendra Paratap who had unsuccessfully campaigned for an Afghan invasion by King Habibullah against British India during the turmoil of the First World War.

Ali was cerebrally aroused to explore the Afghan society of that time and with his impressive language skills, he had access to a cross-section of Kabul’s population, whose ideas and experiences he chronicled with a keen eye and a wicked sense of humour.

If there is an unmistakable sense of pride in Afghanistan’s cultural indebtedness to India, Ali also took pains to illustrate India’s indebtedness to the country of the Ghaznavid Al-Biruni. In his brief recourse to the history of Afghanistan, he attempted to highlight the indelible connection between the histories of India and Afghanistan since the time of Alexander. Ali depicted Afghanistan as the link between Greece and India on the one hand, and between Iran or the ancient Persia and India on the other, for it is through this land that Greek and Persian art and architecture travelled to India.

The history of cultural interdependency of India and Afghanistan impressed Mujtaba Ali so much that he prophesized a greater degree of cultural exchange between Afghanistan and India in the future. But unfortunately, his prophecy appears to us rather naive in the light of the tragic history of Afghanistan especially since the 1970s and the ravages suffered by the country due to the interference of imperialistic forces.

Mujtaba Ali’s exploration of Afghan nationalism and the tradition/modernity debate is very significant. In ‘Deshe Bideshe’ Ali’s optimism resonates with Rabindranath Tagore’s ideal of a pan-Asian nationalism as he had envisioned during his trip to Iran and Iraq in 1932, merely four years after his pupil, Mujtaba Ali, and written in his travelogue, ‘Parosye.’ Had Mujtaba Ali been alive, he would have raised his voice for sure and would have been pained at the present day Afghan horror.