Pragyasundari Devi turned Jorasanko Thakurbari kitchen to a centre of liberal feminism

The date was May 7, 1911. Rabindranath Tagore’s 50th birthday. The large Thakur family at Jorasanko decided to celebrate the occasion on a grand scale. A long list of invitees were drawn that included members of the extended family, friends and well-wishers. Elaborate arrangements were made and the most delectable dishes were served on the occasion. Rabindranath’s young niece, Pragyasundari Devi, had rustled up a special sweet dish that was served to guests. She had named it ‘Kavi Smabardhana Barfi.’ Guests were floored by the taste of the ‘barfi’ stuffed with cashews, pistachios, almonds, raisins and covered with gold and silver slivers. The inventor of the dish, Pragyasundari Devi was naturally impelled by cooking enthusiasts to share the recipe and when she spilled the beans --- her audience was dumb-founded. She had prepared the dish with cauliflower!

Pragyasundari Devi (1884 – died 1950) hailed from the illustrious Thakur-Bari. Of the 14 children of Maharshi Debendranath Tagore, Hemendranath was his third son and Rabindranath’s elder brother. Hemendranath was a scientist and he was married to Maharshi’s close friend, Haradev Chattopadhyay’s daughter, Nripomayee, a self-taught artist. The couple had 11 children and Pragyasundari Devi was their fifth child and second daughter. Her father was very enthusiastic about cooking and wanted to write a cookbook which he could not but his daughter, Pragyasundari Devi did.

She emerged from the glorious Tagore household in Jorasanko who, in addition to reading widely, writing verse and editing magazines, ventured into a virgin territory. She transformed the humble kitchen into a centre of aesthetics and innovation, exploring and documenting the traditional knowledge of the culinary arts and folk medicine within the liberal feminist framework of the Bengal Renaissance.

She emerged from the glorious Tagore household in Jorasanko who, in addition to reading widely, writing verse and editing magazines, ventured into a virgin territory. She transformed the humble kitchen into a centre of aesthetics and innovation, exploring and documenting the traditional knowledge of the culinary arts and folk medicine within the liberal feminist framework of the Bengal Renaissance.

Following the example of her father who loved cooking, she collected and perfected recipes throughout her life, with the precision of a chemist (her father was one) and the flair of an artist (her mother was a painter), writing detailed notes and instructions about each recipe in her diaries. Beginning in 1897, Pragyasundari Devi edited an in-house women’s magazine, ‘Punya’, which not only included recipes collected by her but also the market price of vegetables and fish for instance, she wrote, one ser rohu fish would cost three or four annas, an egg cost one paisa, 20 tomatoes sold for two annas and so on and so forth!

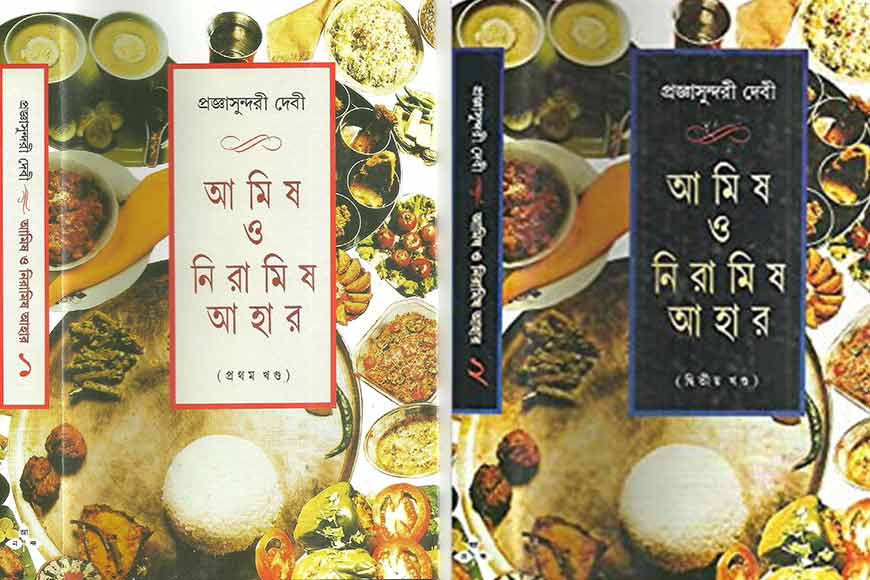

Cookbooks by Pragyasundari Devi

Cookbooks by Pragyasundari Devi

On March 11, 1891, Pragyasundari was married to young author, Lakshminath Bezbaroa, who is considered the father of modern Assamese literature. Bezbaroa’s family was not very happy about the alliance because she hailed from a Pirali Brahmin family and was western educated. Bezbaroa was an emancipated man who always encouraged his wife to pursue her hobby. She accompanied her husband to different parts of Bengal including Howrah, Sambalpur, Jharsuguda (both in Odisha) and during her stay in those places, she meticulously collected local recipes.

Bezbaroa was also an expansive gourmand. It was his idea that Pragyasundari Devi should publish her recipes — a truly novel idea at the time — and after a great deal of hesitation, she mined her notebooks to publish a volume of vegetarian delicacies. Her first cookbook, ‘Amish O Niramish Ahar’ was a ‘significant’ early cookbook in Bengali language, published in 1902. Cookbooks were rare in those days but surprising all expectations, her debut edition sold out quickly. In her foreword, she warned readers that ‘spending a lot of money is no guarantee for good food,’ as she encouraged the efficient use of inexpensive seasonal vegetables.

Also read : What did Leela Majumdar share in her Rannar Boi?

Her cookbook documented recipes for traditional Bengali dishes that were previously not recorded in a language that was distinctly different from the semiotics of renaissance Bengal, applying a vocabulary that was exclusively employed by women within the bounds of the domestic space. ‘Her recipes were mostly gleaned from rural Bengali life. The synonyms used in the Bengali kitchen were also typical of Bengali women's own language,’ writes Chitra Deb, showing how terms like ‘daagdeoa,’ which usually signifies marking becomes an expression denoting the act of cooking spices in ghee.

She published a second vegetarian cookbook, ‘Aaro Niramish,’ and later two volumes of non-vegetarian recipes. She also wrote a cookbook in Assamese language, ‘Rondha Borha’ and one final book, ‘Jarok,’ that collected all types of pickles and preserves. She dedicated this book in the memory of her young deceased daughter, Surabhi.

The innovative spirit of Pragyasundari Devi also flowered in her preparations of traditional Bengali food, as she created new dishes out of old recipes by altering their ingredients: most of these new recipes were named after her near and dear ones, such as ‘Dwarkanath Phirnipillau’ or ‘Surabhi Kheer,’ named after her deceased daughter. Adding her own creative touch to traditional European recipes, she would often come up with number of hybrid recipes born out of a fusion of European and Indian culinary operations. The hybridization of Indian food is quite evident through the frequent use of the term ‘curry’ in her books. To the traditional European recipes like custard sauce, she would often add oriental spices such as nutmeg and clove and would often top it off with a generous serving of ghee, thereby altering the European recipe to appease the Indian palate.

Pragyasundari had immense knowledge about different combination of spices to make unique ‘Pan’ (betel leaf) recipes. She has penned about a dozen ways to created new flavours in ‘Pan’ (betel leaf). Her culinary expertise was deeply appreciated by Rabindranath Tagore, who had preserved a copy of ‘Aamish O Niramish Aahar’ in his library. Pragyasundari’s talent and arduous labour elevated the humdrum and uneventful act of cooking to the stature of an art form, thereby becoming one of the foremothers of liberal feminism in India that sought for women's liberation within the patriarchal system.