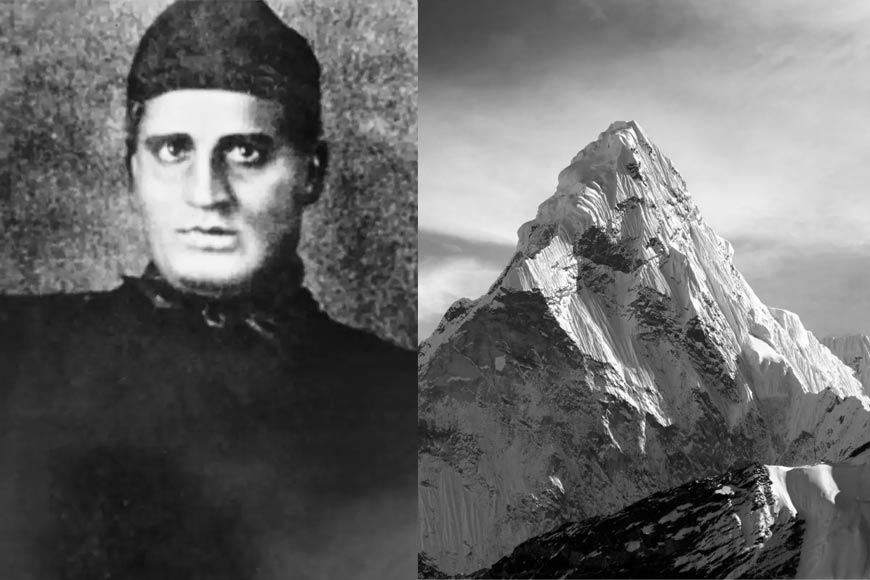

Should Mt. Everest be named Sikdar Parvat after Radhanath Sikdar?

A recent letter stirred the hornet’s nest, not above the world’s highest peak, but down below in the world of mountaineering. Kalyan Chakraborty, Secretary of the Radhanath Sikdar Himalayan Museum, wrote a letter to the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute (HMI) Principal that said: ‘At the order of Colonel Andrew Scott Waugh, then surveyor general of India, Sikdar started measuring the height of mountains. We recall the dichotomy of colonial science. Sikdar had to fit himself into the early colonial scheme of the rulers to self-cultivate his curiosity driven scientific expertise from within that structure. Whenever the latter clashed with the former, Sikdar’s aspirations were thwarted.’ And if people in Nepal can call Mount Everest Sagarmatha and the Chinese have named it Qomolangma, why cannot it be called Sikdar Parvat (mountain) or Sikdar Sikhar (peak) in India?

Well, a tough question indeed, only if India can get past the colonial hangover. But who was Radhanath Sikdar? He will always be remembered as the Indian mathematician who measured the height of Peak XV – later to be named Mount Everest, the highest peak in the world. And he achieved the feat without any modern equipment way back in 1850’s. But just like many Indian geniuses were not recognized by the British and all the credit to discoveries and inventions glorified in the name of the Europeans instead, Sikdar also never got his due credit.

Sikdar calculated the height of the peak he was assigned to at exactly 29,000 feet, but Colonel Andrew Scott Waugh added 2 feet to make it appear a more credible figure. The official height was announced in 1856, as 29,002 feet. In 1865,

“Why should not the Indian mountaineering fraternity call the peak Mount Sikdar seven decades after British rule came to an end? We should observe May 29 as Mount Sikdar Day. Let there be a change,” says Group captain Jai Kishan and HMI principal. The mountaineering fraternity of Darjeeling believe the world's highest peak should have been named after him. Interestingly, many documents related to Radhanath Sikdar is still harboured in a hidden gem of Chandannagar – the Himalayan Museum. This is where Radhanath Sikdar, the almost forgotten genius lived his last years and died in 1870.

In 2013 is the bi-centenary of his birth was celebrated rather inconspicuously. Radhanath Sikdar was born at Jorasanko, near the contemporary North Kolkata’s din and bustle of Barra Bazaar in 1813. During Radhanath’s infancy, Bengal was yet to emerge from the cocoon of blind scruples, dogmatism, myopic social attitude and aversion towards the scientific metamorphosis that was then sweeping all over the Western world.

Also read : The man who made Mount Everest famous

He was a brilliant student of Mathematics at Hindu College and had mastered Newtonian mathematics and physics and invented a new way of drawing a common tangent to two circles when he was in his teens. During graduation, Radhanath delved deeper into the nuances of “Hard Science”, with his penchant for practicing Spherical Trigonometry, following the footsteps of Hellenic mathematicians Thales, Archimedes and Eratosthenes. He was taught about Sir Isaac Newton’s magnum opus on physics and mathematics. Radhanath also showed an interest in astronomical observations. His expertise in Trigonometry earned him a reputation within the “Great Trigonometrical Survey of India” in 1830, when he was appointed at just 18.

In 1831, surveyor-general of India George Everest was looking for a mathematician who had specialized in spherical trigonometry to join the Great Trigonometric Survey. Sikdar, was appointed in that post, as a “computer”. His salary was Rs 30 per month. Sikdar travelled across India to conduct geodetic surveys. Geodetic surveys are done to accurately measure and understand changes in Earth’s geometric shape, orientation and gravity field.

Sikdar calculated the height of the peak he was assigned to at exactly 29,000 feet, but Colonel Andrew Scott Waugh added 2 feet to make it appear a more credible figure. The official height was announced in 1856, as 29,002 feet. In 1865, it was confirmed that this was indeed the world’s tallest peak instead of Kanchenjunga. George Everest retired in 1843 but his successor, Colonel Andrew Scott Waugh, named the peak after him instead of Sikdar who actually measured it and proved it to be the world’s highest.

Radhanath Sikdar was a brilliant student of Mathematics at Hindu College and had mastered Newtonian mathematics and physics and invented a new way of drawing a common tangent to two circles when he was in his teens. During graduation, Radhanath delved deeper into the nuances of “Hard Science”, with his penchant for practicing Spherical Trigonometry, following the footsteps of Hellenic mathematicians Thales, Archimedes and Eratosthenes.

The Society showered Andrew Waugh with praise, but the mathematical exploration’s genuine originator, Sikdar, remained beyond the limelight. Despite being the only person to measure Mount Everest’s actual attitude, Sir Radhanath was often awarded step motherly treatment by his English superiors. Colonial biasness was highly criticized in numerous vernacular newspapers like Prabasi, Sandhya and Bharatbarsho.

As the author of Wild Himalaya, Stephen Alter once mentioned: “But the irony is that we all pronounce Everest wrong. Everest pronounced his name not like ‘cleverest’ but like ‘cleave-rest’ and was apparently quite touchy about it being mispronounced. Perhaps that in its own way is the mountain’s revenge on the men who think they have conquered it.” True no name could ever conquer the feat that Radhanath Sikdar achieved.