Switching sides, the flavour of West Bengal 2021

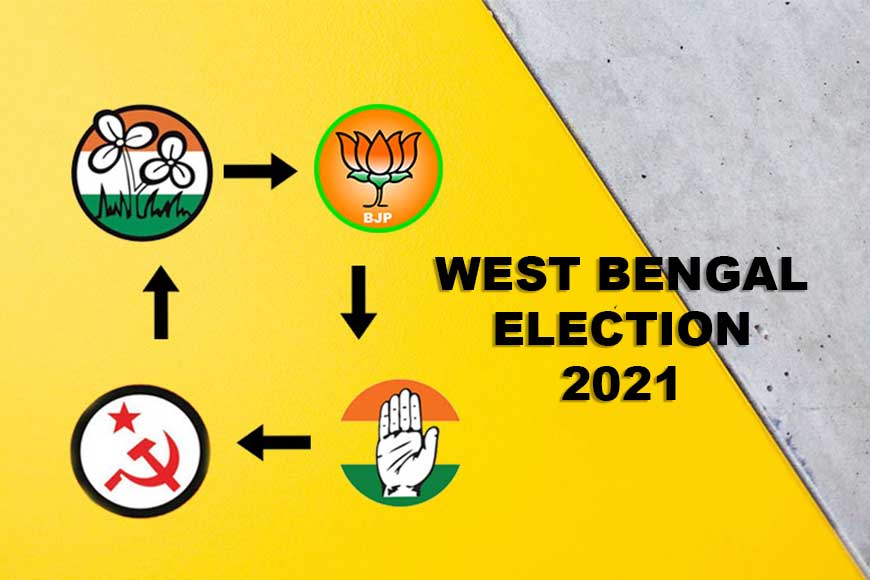

The winds of change, well changing sides actually, have been blowing strongly through West Bengal ever since the Vidhan Sabha polls were announced. As the deadline for filing nominations loomed, we did see a slight lull in the storm. So far, the winds seem to have primarily swept members of the TMC in the direction of the BJP.

The fact of the matter is that after its sudden success in 18 of the state’s 42 seats in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP seems to have acquired a patina of political reliability. Which has resulted in negotiations for the acquisition of power. Rather than build up a local leadership base of their own, they seem to have adopted the policy of ‘borrowing’ leaders from other parties. The second instance of stabbing themselves in the back is their decision to invite candidates willing to contest elections. However, the partners they have picked up in the process aren’t exactly newcomers in the scandals department.

Take Mukul Roy, for instance. In his capacity as the second-in-command of the TMC, he was only the second leader after Atulya Ghosh for whom the media had begun to use the honorific ‘Bangeshwar’. However, as soon as the CBI began a probe into his role in the Saradha scam at the behest of the Supreme Court, he hastily switched sides.

Successive such switches have followed in his footsteps. Suvendu Adhikari’s family currently boasts one minister, one MLA, and two MPs. Surely a record in Bengal. And yet, he is unhappy with TMC. Even if we were to overlook that, what he could have done was to float a new party, as Mamata Banerjee herself once did, or emulated a leader from his own district of Medinipur, Ajoy Mukherjee, who set up a new party in the 1960s. But he has chosen to climb onto the BJP bandwagon.

As things stand, the leaders who quit TMC in a huff because they weren’t allowed to contest the elections are also quitting the BJP for roughly the same reasons, or perhaps because they haven’t been assigned the constituency of their choice. That list now features the names of Sovan Chatterjee and Baisakhi Banerjee as well. Many have actually paid a visit to BJP party offices to shower them with brickbats. Indeed, the BJP seems to have more candidates than there are voters in the state. Could that be the reason why its followers are now unable to gather even for Narendra Modi or Amit Shah’s public rallies? Whatever else they do, these examples do not indicate any loyalty for the party ideology.

It is important to mention here that our country has a strong anti-defection law, incorporated into the tenth schedule of the Constitution in 1985. However, that applies only to elected MLAs and MPs, who stand to lose their elected posts if they go against the party line in their respective Houses.

It has now been over three decades that the law was passed, yet the tradition of switching sides remains as strong in Indian politics as ever. In recent times, the BJP successfully persuaded a handful of ministers in Puducherry to resign and thereby topple the Congress government. In the incumbent Andhra Pradesh Vidhan Sabha, opposition MLAs were actually rewarded with ministerial berths after switching sides, because the Speaker chose not to penalise them. The loophole in the law is that the final decision to punish the deserters rests with the Speaker, who is, of course, nominated by the ruling party.

In recent times, MLAs who switched sides have returned to power in Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh. Since they came to power at the Centre in 2014, the BJP has taken over in one Northeastern state after another by engineering defections and causing elected governments to fall.

Consequently, the law has proved powerless to stop defections. Voters do have the power to mete out the ultimate punishment, but that isn’t easy to do when the defectors join a large, powerful party. And if they manage to win the elections, then all sins are forgiven.

However, exceptions do exist, not least in Bengal. As one of the stars of chief minister Bidhan Roy’s cabinet, Siddhartha Shankar Roy chose to resign over an ideological dispute. He subsequently resigned from his post as an MLA too, and ultimately quit the Congress. Contesting as an Independent candidate from his earlier constituency, he scored a convincing victory as well, thus demonstrating the difference between unprincipled defections and principled protest.

In the end, when the Constitution and public mandate fail, the only way of preventing defections is perhaps a social boycott. Once again, West Bengal provides an example. In 1967, the first United Front government assumed power in the state. Nine months later, 17 MLAs led by Prafulla Ghosh left the coalition to form a new government with support from the Congress. The then Vidhan Sabha Speaker Bijoy Banerjee challenged Governor Dharamvir’s decision to allow the formation of the new government. Simultaneously, a public and social outcry arose over the actions of these 17 MLAs, causing the Prafulla Ghosh government to resign just over a month after its formation.