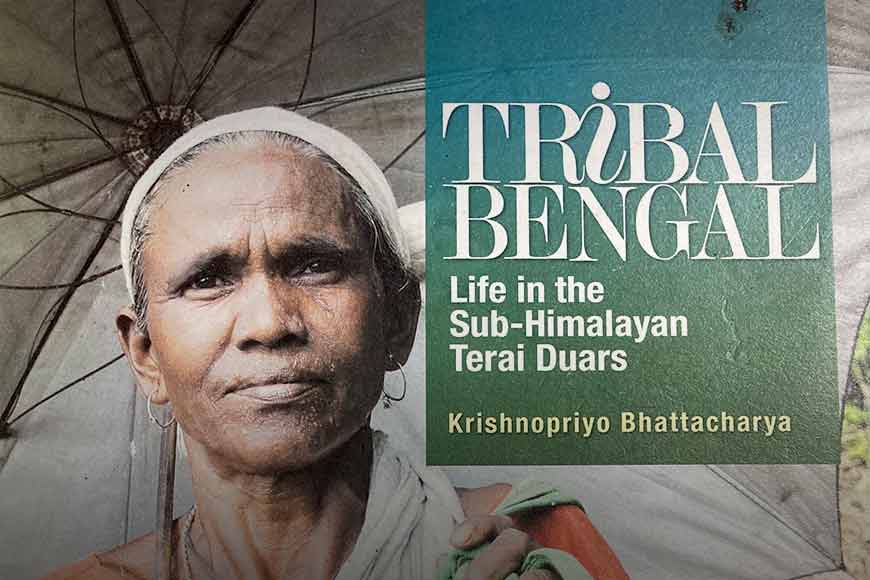

Tribal Bengal, a book like no other

“As among the Kachharis, Bathou is the chief deity of the Meches. They worship the sijou (euphorbia) tree, which they plant in the northeast corner of the courtyard of their house. Another important deity is Mainao, whom the Meches regard as the guardian of the paddy fields.”

How much of the above paragraph is intelligible to you? How many of the proper nouns ring a bell? The answer is likely to be zero or close to it for most of us. Which is why we need anthropologist, poet, and writer Krishnopriyo Bhattacharya and his book ‘Tribal Bengal: Life in the Sub-Himalayan Terai Duars’ (Niyogi Books, Rs 1,495). First published in 2019, the book has just gone into a reprint.

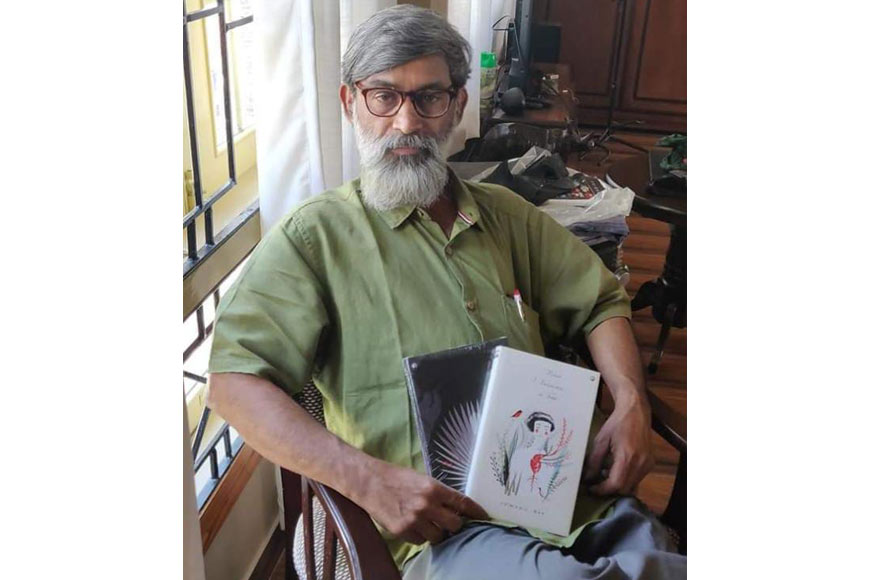

Author Krishnopriyo Bhattacharya

Author Krishnopriyo Bhattacharya

#Siliguri: There cannot be a better book than “Tribal Bengal” on the Tribes of North Bengal. A hardcore field person, Krishnopriyo Bhattacharya Ji, who has spent a few decades with the communities he has written about ...

— Raj Basu (@actraj) April 25, 2019

Do not let the semi-academic sounding title fool you. This is an excellently designed book filled with brilliant photographs taken by the author himself, easy to read chapters, and easy to understand data, all presented in an informal, free-flowing, anecdotal style. And yet, it offers a perfect starting ground for the more serious researcher too. Divided into two parts (Indo-Mongoloids, and The Proto-Australoids and Others), the book provides a panoramic view of the state’s incredibly rich tribal heritage, a large chunk of which has already vanished, and more is likely to follow unless the mainstream takes note.

The Limbus

The Limbus

As a 22-year-old graduate brimming with enthusiasm for his first job, the author joined the state government’s Backward Classes Welfare Department in 1981, and thus began a journey that has only gathered speed over the years. Now retired, Bhattacharya gives every indication of producing more such works since he has more time on his hands, which is excellent news.

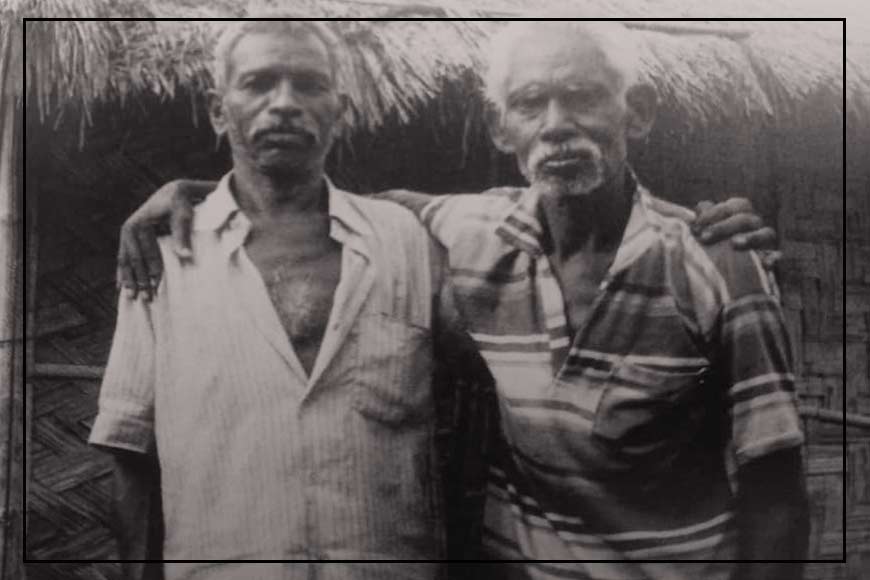

The Raj Gonds

The Raj Gonds

The documentation, fieldwork and painstaking research that lies behind the seemingly effortless brilliance of a book like ‘Tribal Bengal’ may not be everyone’s forte, but there is nothing to stop you from enjoying the fruits of the labour. For Bhattacharya, the people and places he has written about and photographed are real, tangible entities, not just names in a government department file. He knows a great many of these people personally, and presents their individual stories, rather than simply compiling information.

It is through such stories that you will know the people behind the names. People such as Krishna Parhaiya, a member of the Parhaiya tribe, who migrated from Bihar’s Palamau region to Bengal in search of tea plantation jobs. Or Sukra Asur, with his “illustrious proto-Australoid tribal face and physique”, who knows nothing of his Asur heritage, or his mother tongue, Asuri. Or Basanti Soy-aa, the Ho woman who gave Bhattacharya a list of patrilineal Ho killis (clan names). Or Seth Ekka, one of the author’s Oraon friends during his boyhood in Kamakhyaguri.

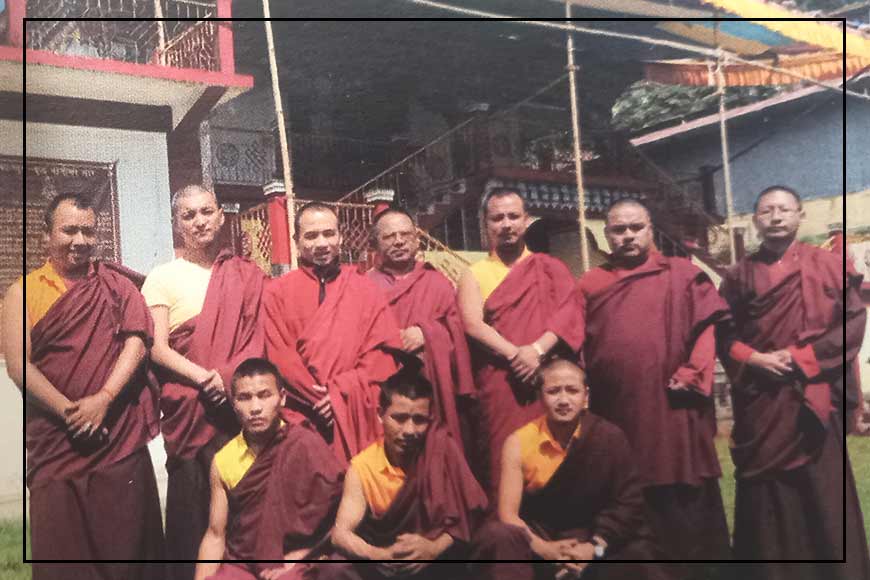

The Sherpas

The Sherpas

In one chapter of his book, Bhattacharya writes, “As I had grown up in the Duars, my upbringing was different from the Kolkata-dominated Bengali mindset.” The 60-something writer, researcher, and photo-ethnographer speaks Nepali, Kurukh (a Dravidian language spoken by nearly two million people in Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal, Assam, Bihar and Tripura), Bodo, and Sadri (an Indo-Aryan language spoken in Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Bihar), apart from Bengali and English.

The more you go through this book, the more you realise what a critically important document it is, and exactly how rich a tribal legacy we have inherited. At the end, the author provides a few appendices listing the current status of the tribes listed in the book. And you realise that many of them are close to extinction in the state. Already, without being physically extinct, many tribal communities face extinction in terms of their language, way of life, and culture, which is no less alarming.

Prior to this groundbreaking book, Bhattacharya authored two dictionaries in Bengali and IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) of several of Bengal’s scriptless tribal languages in the 1990s, a book titled ‘Silent Departure: A Study of Contemporary Tribal Predicament In Bengal-Duars’ (2007), as well as several volumes of Bengali poetry. And he still found time to double as the Duars correspondent of two prominent Kolkata dailies for over a decade.

Totopara

Totopara

Archivists and chroniclers such as Krishnopriyo Bhattacharya are rare specimens of humanity. They are people who combine the passion of an amateur hobbyist with the rigorous discipline of a professional academician, and the result is a book like ‘Tribal Bengal’.