When Scrolls Speak, Laltu Patua Sings - GetBengal Story

In the scorching heat of summer, the dying Ajay River flows slowly, its banks covered in layers of white sand. Beneath the bright blue sky, a farmer rests under an unnamed tree standing at the corner of open paddy fields. A Toto hums past, breaking the silence of the afternoon. In this atmosphere, the sound of a rustic melody drifts in from afar, where a wandering minstrel sings: “Aaj boner o boner phool tule go, Radha-Krishner gole bonmala.” The mystic charm in the singer’s voice cools the burning afternoon as if it were touched by the soothing showers of monsoon.

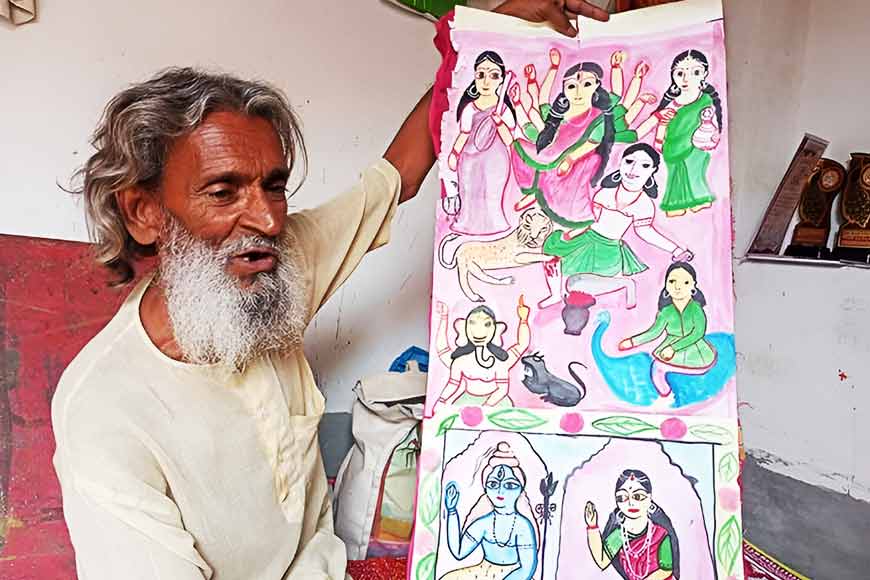

The singer is Laltu Patua, an artist of 64 years of age, who has maintained the centuries-old tradition of patachitra gaan in Birbhum district for the last 47 years. Even now, he earns his living by going from home to home, showing scroll paintings, and singing along with them. With his paintbrush, he tells stories of Lord Krishna and Mahaprabhu Chaitanya. In the paintings and in the songs, the mythological gods become warm humans, human companions of the soul which is not beyond distance.

In this age whenever we talk about patachitra, the first name that springs to mind is the Naya village in Pingla, in undivided Medinipur, which has proudly made its mark on a global scale. However, there have been periods when patachitra flourished through many different areas of Bengal, including the fabulous Kalighat-style of Kolkata, now only a distant memory. Today, there are other traditions that continue aside from the work in Pingla, and remnants elsewhere in rural Medinipur, the Rarh region, and pockets throughout Bengal—but they are scattered, tenuous and diminishing.

All forms of art have a utilitarian function. If they didn't, the meaning and practice of the art would be lost. There are examples of clay dolls made by artisans who made the dolls for children to play with. When children do not play with them anymore, they become empty, lifeless objects; dusty, useless decorations for others' egos and display cases. Likewise, the entirel meaning of patachitra can only be realized when the painter is travelling from house to house carrying the scrolls, singing the stories while displaying the paintings. Modern experiments—having patachitra displayed on mugs, sarees, shirts, or trays—may preserve the craft as a commercial venture, but the spirit of the art is irretrievably lost. Even taking the scrolls and putting them in a gallery fails to capture any of its true meaning.

In this context, we could refer to Laltu Patua of Itagaria village in Birbhum, who has continued to practice the tradition in its integrity. He hand paints his scrolls, carries them to people's homes, and his songs represent the scrolls. Thus, Laltu keeps not only the art alive, but the accompanying folk-educational value. He still walks from village to village singing and showing his scrolls at hight of day. He learnt to paint and sing from his father, Kader Patua, before expanding his style based on his life experiences. "The length of the song depends on the scrolls," he explains. "Sometimes it takes twenty minutes, sometimes an hour".

For decades, this has been his only livelihood; he has never done any other job. He travels through Bengal with his scrolls for every village fair and festival. He has sung at Baharampur during the Charak, at Dubrajpur and Durgapur during the Rath Yatra, and also at Kenduli's Jaydev Mela, the Poush Sankranti fair. At fairs, his granddaughter often travels with him to provide accompaniment by playing a dhol while Laltu sings.

Laltu Patua's brush strokes are straightforward but powerful. His mythological characters do not only radiate divine splendour but shine with human warmth and modesty. His patachitras and scrolls, free from stylistic complications and urban commercialization, have retained a folk sensibility and approach. He uses his own herbal dyes and paints on handmade paper with a cloth backing for durability. Some of his scrolls reach heights of fourteen feet, stranger things have happened, usually Kings Harishchandra or Dasharath, or the goddess Mahishasuramardini in her lion-riding condition. For the spring festival he painted Maa Basanti and for Rath Yatra he would paint episodes related to Chaitanya Mahaprabhu . His two large scrolls of Chaitanya's life are particularly touching - one on Nimai Pandit before his renunciation, and the second scroll is his divine pastimes in Puri after his renunciation. As he sings of Mahaprabhu’s final merging into the deity Jagannath, his voice trembles with devotional emotion.

His art includes the great epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. With poise and richness, he paints the bravery of Dasharath and the birth of Lord Rama, while he equally keeps alive the worship traditions of folk goddesses like Manasa and Shitala through his paintings and songs.

Though he faces challenges, Laltu Patua and his wife Salema Patua do everything to sustain the dwindling art form of patachitra. Salema is a source of strength for him, accompanying him in his struggles and devotion.

The scholar Tarapada Santra wrote that early patachitra was painted on palm leaves, then on cloth (named kanthapat), and later, handmade paper. He noted that patuas used to create three kinds of scrolls: long vertical scrolls depicting mythological and social stories, horizontal scrolls, and square scrolls, called jadupat or chakshudan pat.

Folklore researcher Dr. Samipeshu Das added that Birbhum’s patachitra is one-of-a-kind in Bengal, is untouched by urbanization. There are two traditions that survives in Birbhum; simple scroll paintings performed with singing, and the “Durga Patachitra” which is only painted for Durga Puja, and worshipped as goddess Durga herself. The traditions of Itagaria, Shatpolsa, and Bhramrkol villages continue to follow the path of longue scrolls and pata songs, generation after generation. Themes range from the Ramayana and the slaying of Mahishasura to contemporary issues like women’s rights, education, and environment. Unlike commercialized crafts, Birbhum’s scrolls still use natural colors and maintain their simple folk expression. Even the songs carry distinct melodies unique to each district, making them a cultural treasure of Bengal.

As evening takes its leave and the sun makes its descent in the west, Laltu Patua’s tired yet soulful voice rises one more time: "Joy Jagannath, joy koro baba Balaramer doy." The signs of age are apparent on his face, as white hair hangs to his shoulders, and the white beard outlines his cheeks, when his frail body spoke of labor. However it is the struggle that takes you further than an artisan; Laltu Patua is more than an artisan; he is a sage of his art. A totality of folk creativity, Laltu Patua's voice and artistry will still seat an audience on a tractor ride across rural Bengal, in a song, in a painting, in a story.

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here