Author Sumana Roy believes in narratives of stillness

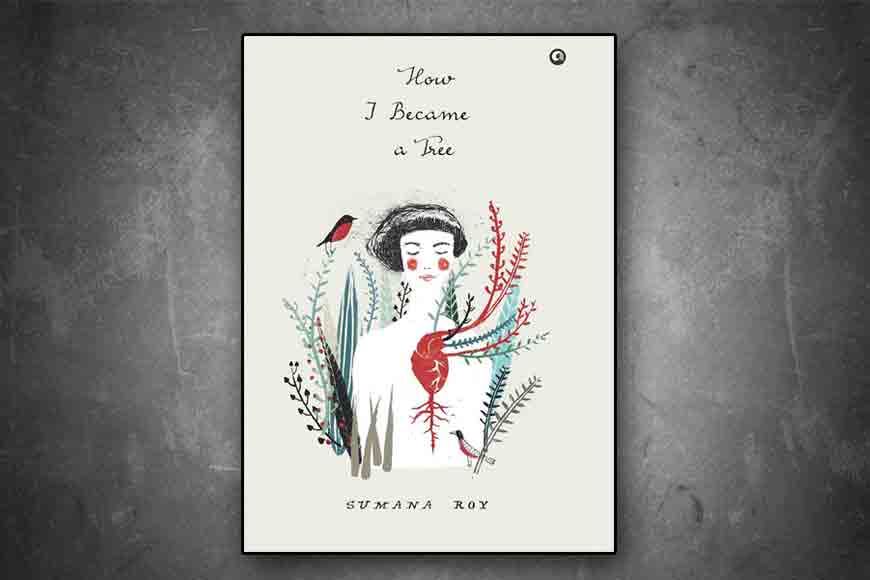

Sumana Roy’s first book, How I Became a Tree, a work of non-fiction, was published in India in February this year. Her poems and essays have appeared in Granta, Guernica, LARB, Drunken Boat, the Prairie Schooner, Berfrois, and other journals. She lives in Siliguri in India.

• How are you feeling now, that your book How I Became a Tree has made it to the Mumbai Lit Fest award category, featuring in the same list as Shashi Tharoor and others?

How I Became a Tree was shortlisted for an award in the non-fiction category for first book. I’ll be completely honest with you – I didn’t feel anything at all. No one writes for awards. That, of course, is a cliché. I’m just grateful that a book like How I Became a Tree was published.

• Many of your stories have nature in it, even your latest book published by Aleph. Why do you bring a human element in nature?

In my mental world, there is almost nothing to demarcate the human from non-human. If a plant or animal or a thing interests me, I think and write about my experience of it. The same process of curiosity and interest applies for the human. I’ve never set out to write exclusively about ‘nature.’ I’m, in fact, uncomfortable with the category.

• Does your upbringing and place of birth have any influence on your writing? If so why and how?

I was born in North Bengal, and it is where I’ve spent most of my life. Siliguri would, quite naturally, have an effect on the person I would become and also perhaps some of the things that would interest me. I don’t understand – or even like – the new Siliguri. The town I grew up in had an intimacy and semi-secretive life that made it possible for me to imagine my life as being related to many I did not know, strangers and the streets of literature, and a kind of quiet contentment that would seep into the person I’d become. What I miss most from my life here in the 80s and 90s is the indulgence, and even cultivation, of uselessness. How I miss the religious dedication of collecting moss for jhulon!

• How did your love for nature grow?

In exactly the same way my love for humans must have grown – from curiosity. How I Became a Tree came from the silly impulse to reject the human world for plant life – it soon grew into a comparative understanding of the human and the tree.

• You are also into poetry. What kind of poetry do you write? Where have you been featured?

I write things that resemble poems. I find it difficult to call them ‘poems.’ I say this because I don’t think any of us really know what a poem looks or sounds like. In that, it is quite akin to love – we experience it but are unable to define it.

It’s very difficult to say what these poem-like things are about. I’ve written about plant life, about emotions, places, art, in other words, my experience of the world.

Some of my work has been published in Granta, Guernica, Prairie Schooner, The White Review, Berfrois, Cha, Himal Southasian, among others.

• What are your future plans as an author? Are you working on any other book?

My first novel, Missing, will be published by Aleph in May 2018.

• You are an extremely lyrical author, using a lot of imageries. How do you think the style of writing has changed in recent times?

Language is always evolving, of course, and with it so do genres. The most difficult task facing the writer today is in how s/he can retain the reader’s interest in a time of shrinking attention spans and a culture of visual consumption that is inclined more towards surface than depth. I need to think about this more carefully, but I have the sense that the speed with which the reader consumes words (I think the reader is rejecting more than she is retaining, a phenomenon that is a side-effect of scrolling for bullet points in news items) online cannot be the speed of narrative. I could be wrong, but I have the sense that the exhaustion caused by the speed of news will make literature a place of rest. And so, we shall go to books that give us a world where we see things differently and experience time more fully and differently. I think we are in a moment of transition where everyone, writer, musician, filmmaker, perhaps even the painter, is trying to replicate speed to fight the speed of technology. It is possible that the answer to fighting that kind of artificial speed is to do quite the opposite, to move towards narratives of stillness.

• Did Bengali authors like Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhay influence you in bringing in this element of nature?

Bibhutibhushan is a writer I return to often. I’ve written about Aranyak in How I Became a Tree.

• What kind of books do you love to read? And what do you do in leisure?

I find that I do not enjoy reading fiction very much anymore. The poem and the essay are my favourite forms, and I read both quite regularly. Poems – songs – by Rabindranath, Jibanananda Das and Shakti Chattopadhyay’s poems, Amit Chaudhuri’s poems and essays (I read his fiction as one does poetry) – I return to them over and over again. I find it difficult to answer this question in a generic way. So, here’s a list of what I’ve been reading recently: Amit Chaudhuri’s A Strange and Sublime Address which I probably know by heart but must return to all the time; James Salter’s Light Years, from which I read a paragraph or two arbitrarily; Richard Ford’s The Sportswriter; Gavin Francis’s Adventures in Human Being.

Quite honestly, I do not understand the difference between work and leisure anymore. Ever since I quit teaching full-time, I find myself fortunate to be in a situation where work is my space of leisure. Having said that, it’s difficult to think of reading and writing as work. I like listening to music, I used to be a gardener until I broke my arm last year (I haven’t returned to it since), I daydream, I nag my closest friend, I watch food programmes on YouTube – I have a great talent for the inconsequential.

• Do you think young writers of Bengal or from Bengal have a good future?

I haven’t thought about this, but that’s only because one doesn’t think of writers as people limited by geographical location. I read writers writing in Bangla but have never thought of them as writers from Bengal.I think anyone who writes about the things s/he loves has a chance of being read – good writing will never go out of fashion.

Also, I hope you won’t mind my saying this, but I think it is not always about ‘young’ talents. I say this not from a sense of political correctness about ageism but from an awareness of people who’ve been able to create opportunities for themselves only later in life, after the expiration of ‘Under 30’ and ‘Under 40’ tags that have, for the last couple of decades, defined our assessment of writing talent. It is not only that it is often women and people from marginalised sections who are able to come to writing or the arts slightly late in life. It is because talent often manifests itself in an accident of circumstances beyond the gated communities of university, writing programmes, publishing track, and other such laboratory factors. The flowering of such talent, surprising because of its supposed untimeliness, is often a thing of wonder.