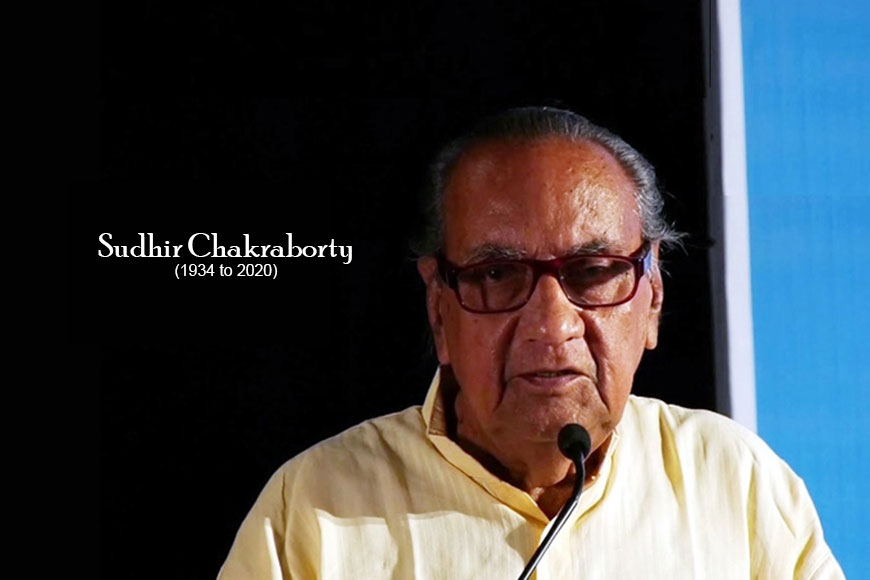

A final farewell to the doyen of Bengal's folk culture

Rahul Sen is the editor of Bibhab Magazine. A reading enthusiast. Collector of old songs, recordings and literary works.

On December 15, a man named Sudhir Chakraborty left all material con-cerns far behind and stepped out into the wide unknown. The man who walked ‘Along Deep and Lonely Alleys’ to gather treasure for us.

Born on September 19, 1934 in Shibpur, the young Sudhir was a first-hand witness to what Bengalis know as ‘antarjali jatra’, the agonising wait for death on the banks of the holy Ganges, in the belief that death in such a holy place transports the soul straight to heaven, a practise that has mercifully gone out of fashion. His childhood experiences of death imbued Chakraborty’s writings with both a deep sense of compassion, as well as detachment.

With World War II looming large, Shibpur became a target for enemy bombing. Accompanying his father and riding on his elder brother’s shoulders, Sudhir set off for their ancestral village of Dignagar in Nadia district. Ravaged by an epidemic, however, Dignagar was all but deserted. The exquisite terracotta work on the panels of the Raghabeswar temple within the village sowed the first seeds of interest in folk culture in the mind of the young boy, an interest that would shape the course of his writings. However, only a year later, the family was bound for Krishnagar, leaving the unhealthy environs of Dignagar behind. The year was 1942, and Sudhir was still only eight.

Meanwhile, his life as a writer was taking shape. As a first-year stu-dent in Krishnagar, he had contributed a piece to the college maga-zine, entitled ‘Pothe Jete Jete’. Then came memoirs to Jibanananda Das in local magazine ‘Homshikha’. In Kolkata, his first published work was an essay in a publication titled ‘Notun Sahitya’, at the in-sistence of its editor, the late Anil Kumar Sinha.

From Dignagar Upper Primary to Debnath School in Krishnagar, which he left in 1951 as part of its last batch of matriculates. On to Krishnagar College, where among his fellow students was a young man nicknamed Pulu, who the world was to know as Soumitra Chattopadhyay. In Chakraborty’s mind, his college played a critical role in laying the foundation of his life, which is why he unhesitatingly chose to go back there at the beginning of his teaching career, even when a chance to teach at Presidency College had presented itself. All owing to his belief that his formative years had been shaped by the teachers and environs of his alma mater.

Before that, he travelled to Kolkata for a master’s degree, where his batchmates included such future luminaries as Sisir Kumar Das and Amiya Bagchi, among others. The Kolkata experience also marked his entry into a world of immense cultural richness, adorned with the plays of Sambhu Mitra, the cinema of Satyajit Ray. His teachers included such legends as Pramathanath Bisi, Narayan Gangopadhyay, and Shashi Bhushan Dasgupta. The Wellington College hostel where he stayed was the regular haunt of young artist and writer friends, who would go on to rule Kolkata.

At Mitra and Ghosh publishers on College Street, he would meet such literary giants as Bibhuti Bhushan Bandyopadhyay, Manoj Basu, Satinath Bhaduri, Kalidas Roy, and Kumud Ranjan Mullick. The indulgent company of Buddhadeb Basu at Kabita Bhaban drew him further into the world of literary achievements. In 1958, he joined Vivekananda College in Barisha, Kolkata, and went back to Krishnagar in 1960 as a government appointed teacher.

Meanwhile, his life as a writer was taking shape. As a first-year student in Krishnagar, he had contributed a piece to the college magazine, entitled ‘Pothe Jete Jete’. Then came memoirs to Jibanananda Das in local magazine ‘Homshikha’. In Kolkata, his first published work was an essay in a publication titled ‘Notun Sahitya’, at the insistence of its editor, the late Anil Kumar Sinha. In later years, Chakraborty would go on to write more than 50 articles for the celebrated ‘Desh’ magazine. Describing his writing career, he once said, “Two things interest me beyond all else: songs and villages.”

At the age of 50, he published his first books - two of them at one go – ‘Gaaner Leelar Shei Kinare’ and ‘Sahebdhoni Sampraday o Taader Gaan’. As a young writer, he had published poems in virtually every contemporary publication of repute, but his career as a poet remained short-lived. As a student in Kolkata, he worked as a proofreader for several magazines from the districts, simply so he could buy books of poems by the likes of Nirendranath Chakraborty, Naresh Guha, Buddhadeb Basu, and Jibanananda. The Rs 25 or that he earned was almost entirely spent on such purchases.

His career as a researcher of the folk music of Nadia began almost by accident. In 1970, when he was still teaching in Krishnagar College, a circular arrived from the University Grants Commission, inviting applications for scholarships. A colleague advised him to apply, which he did, and the grant duly arrived.

His career as a researcher of the folk music of Nadia began almost by accident. In 1970, when he was still teaching in Krishnagar College, a circular arrived from the University Grants Commission, inviting applications for scholarships. A colleague advised him to apply, which he did, and the grant duly arrived. Without much thought, he decided on the spot that his research subject would be ‘the folk music of Nadia’.

That was how it began, but the consequences went deep. As the years passed, so his interest in folk culture, folk languages, the music of Lalon, the lyric poetry of Bengal, Rabindranath, even anthropology, grew expo-nentially. Over more than three decades, he scoured various parts of Nadia, Murshidabad, Bardhaman, Birbhum, and Bangladesh on foot, extending the scope of the field surveys begun by Akshay Kumar Dutta. Chakraborty’s fieldwork became a mirror in which was reflected the folk culture of our nation. The outcomes of his research were books such as ‘Baul Fakir Katha’, ‘Sahebdhoni Sampraday o Taader Gaan’, ‘Bratyo Lokayoto Lalon’, ‘Bolahari Sampraday aar Taader Gaan’, ‘Manini Rupmatir Kubir Gnosai’, ‘Bangla Dehototwer Gaan’, ‘Banglay Baul Fakir’, and many more seminal works that became veritable encyclopedias.

In 2002, ‘Baul Fakir Katha’ fetched him the Ananda Puraskar, while Sahitya Akademi conferred their award in 2004. Among other awards were the Sukumar Sen Gold Medal from the Asiatic Society, the Sarojini Basu Gold Medal from Calcutta University, and the Dinesh Chandra Sen award from Rabindra Bharati University. That apart came recognition as an ‘Eminent Teacher’ from Calcutta University, as well as the Shiromani Puraskar and Narsinghdas Puraskar.

Writing relentlessly, he took on the additional responsibility of publishing the annual compilation titled ‘Dhrubapad’ from 1996-2008, after his retirement from Krishnagar College. Unparalleled in terms of content, these compilations remain a treasure trove. Moreover, he edited between 10 and 12 books, while the number of his own published works is 90-odd.

Leaving all those behind, survived by his wife and two daughters, he has now embarked down a deep, lonely alley. His legacy to us is a collection of written works and speeches of immeasurable richness, which are sure to inspire young writers and researchers to explore ever newer depths.