B.A. for Biye: The Quirky Poetry of Old Bengali Weddings - GetBengal Story

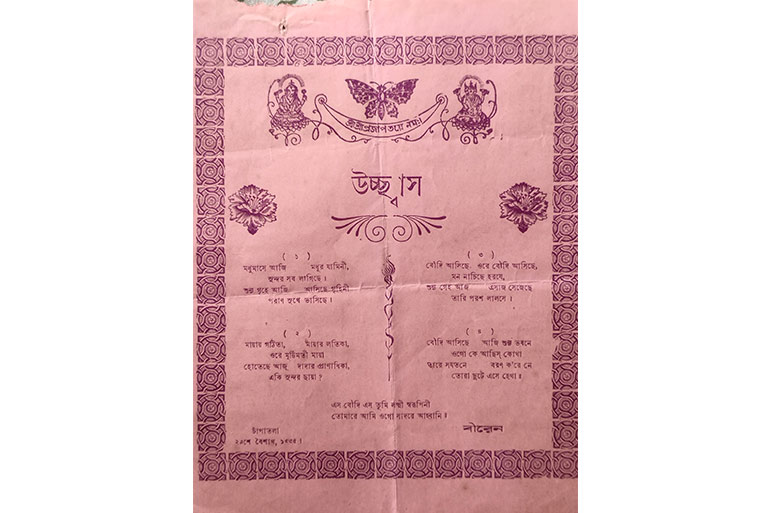

In Bengali families, it was once customary to compose verses for weddings. Surprising as it may sound, this tradition was very much alive even forty years ago. And it wasn’t limited to Kolkata alone—other districts practiced it too. On wedding evenings, when guests gathered, colorful printed copies in yellow, pink, light blue, or green would be distributed, each carrying one or more poems. Later at night, during the groom’s party’s vigil in the bridal chamber, these verses would be recited in a playful tone. Sometimes, instead of a single sheet, a booklet of several pages was published, with titles like Sneho Upahār, Bhakti Upahār, Priti Upahār, Snehashis, Milonotsav, Milonogiti, or Bodhu Abahon.

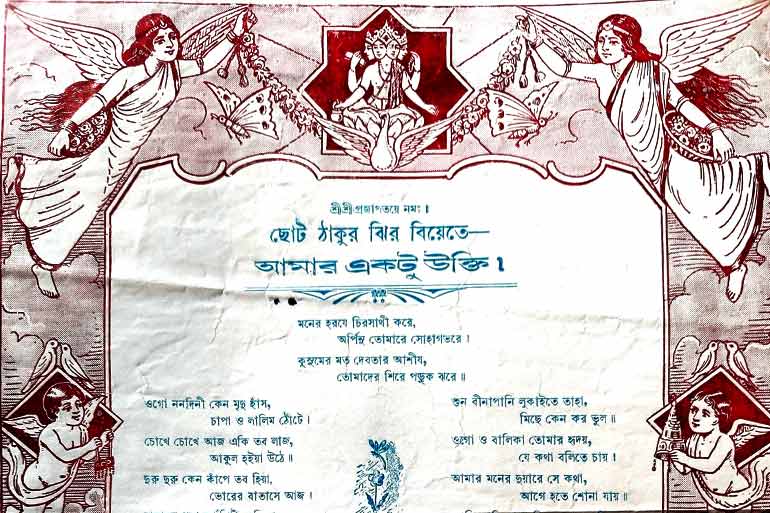

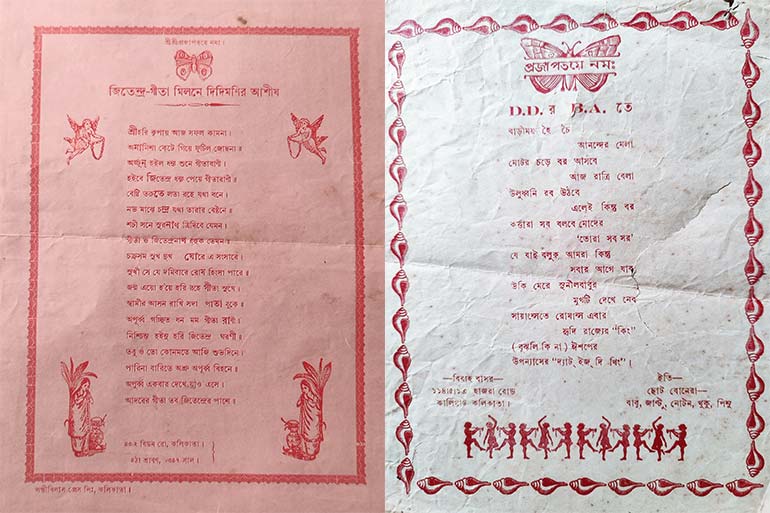

It wasn’t only family members—neighbours, too, who would contribute impromptu verses. Many of them weren’t even formally literate, yet their imagination infused these rhymes and poems with life. The decoration of these wedding leaflets was no less striking. During the British era, some poems featured illustrations of two fairy-like women holding garlands, while others showed two ordinary women in saris blowing conch shells for auspiciousness. The banana plant, an essential element of the wedding canopy, along with shehnai music, also appeared as recurring motifs. Sometimes, these verses were even printed on patterned napkins. Naturally, families on both the bride’s and groom’s sides carried on this tradition.

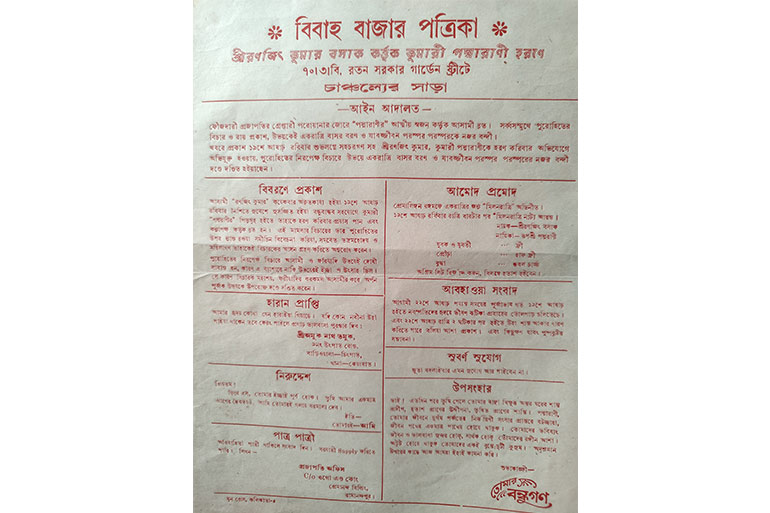

The poems followed the general way of Bengali print literature. They blessed the bride on behalf of elders, carried affectionate greetings from younger siblings to their elder brother or sister, or teased the groom with lighthearted humor about his new wife. At times, tender melancholy entered the verses too—like siblings lamenting the loss of their playmate as the bride left for her new home. The mother-in-law’s advice also found a place: the new bride was now responsible for the household’s storehouse, and must keep everyone in the joint family happy—becoming the goddess of the home. Another delightful feature was the use of Roman letters. The word biye was sometimes written as “B.A.” since both sounded alike in Bengali. Likewise, “DD” stood for didi, or “80” was used in place of ashi.

The verses were full of humour and wit. Take, for instance, the theme of “mon churi”. Inspired by the Sanskrit mantra “Yadidam hridayam mama tadasthu hridayam tava”, it translated into playful lines of “stealing the heart.” Folk theatre (jatra) had long been a favourite of Bengalis, and so there were even short plays written in verse. One such example, titled The Bhishma of Kali Yuga, was composed in the 8/6 beats. In the Mahabharata, Bhishma was an unmarried man who had vowed celibacy. Here, however, fate compelled the modern Bhishma to marry, and thus the short dramatic poem was born. These works, though lighthearted, always remained rooted in contemporary thought. References to sweets like khaja, monda, and mithai often popped up in the verses, along with divine comparisons—many brides were likened to Hara and Gauri themselves.

Similarly, as time passed, the style of these poems had changed too. Instead of a nursery-rhyme-like rhythm such as “Brishti pore tapur tupur,” the poems of the 1970s and 1980s used language that was more like something out of Rabindranath, more poetic and refined. Taste, culture, and the spirit of the times shaped these compositions, yet they never lost their individuality. Children’s mischief, elders’ solemn blessings, and the romantic exchanges of the couple—all were expressed in rhythmic lines that ran parallel to mainstream literature.

Today, much of this tradition has faded away. Among the lost gems is the Gauravachan recited by barbers. Still, thanks to family care, cultural awareness, and the urge to preserve heritage, a handful of these wedding verses remain safeguarded. They stand as charming testaments to Bengali creativity and literary devotion.

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here.