Even after a century, Ritwik remains the most profound cinematic synonym for Partition – GetBengal story

“I never tell an ordinary, sugary-sweet story—where a boy and a girl fall in love, can’t unite at first and feel sad, then finally unite or one of them dies, a cliched, contrived plot made into a film to foolishly make the audience laugh or cry, emotionally involve them in the story, only for them to forget it in two minutes, go home happily, eat dinner, and fall asleep—I am not in that kind of work.

…If you become aware, and after watching a film come out and engage in challenging social oppression or corruption—if I can establish my protest into you—only then can I consider myself successful as an artist.”

During the Partition, Ritwik Ghatak’s family moved to Kolkata. But emotionally, he always considered East Bengal his roots. This familial displacement left a deep impact on him, and this very experience became the central theme of his cinematic language. He saw Partition as a permanent rupture in the consciousness of a nation.

His most famous and influential works—Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), and Subarnarekha (1962)—form a trilogy that portrays different aspects of post-Partition refugee life.

In Meghe Dhaka Tara, we see Neeta, who bears the entire burden of her displaced family alone. For her, Partition is not merely a geographic divide, but a path of oblivion where identity, sacrifice, and love slowly wither away. Neeta’s desperate cry— "Ami bachte chai!" (I want to live)—echoes the existential crisis of an entire nation.

Komal Gandhar leans into leftist politics and theatre as tools for rebuilding consciousness. Here, Partition is not just a historical event, but a symbol of cultural division. Even amidst the conflicts within a theatre troupe, the pain of displacement reverberates.

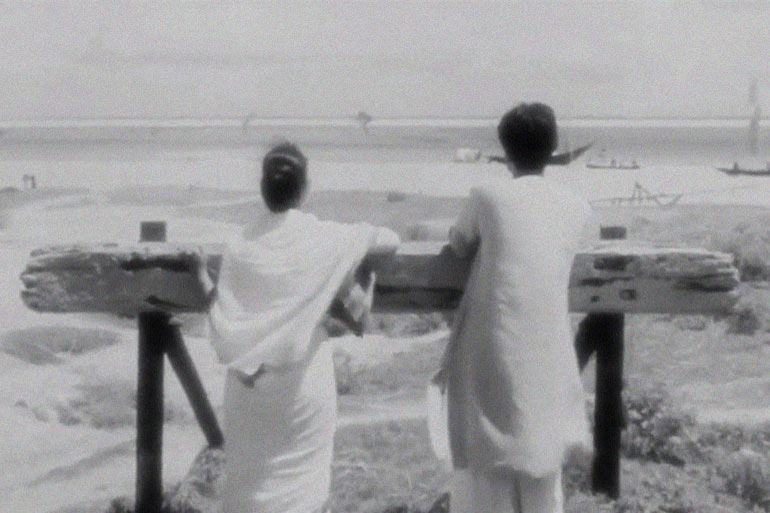

In Subarnarekha, the aftermath of refugee life turns even more tragic. It depicts shelter-seeking, fractured identity, the poverty of the working class, and a dark, ominous future all intertwining into complexity. At the end of the film, the disoriented and devastated protagonist stands by the banks of the Subarnarekha river, which now appears as a border of Partition.

In Ritwik Ghatak’s films, Partition is sometimes the main character, sometimes an undercurrent presence. In one interview, he said:

“Partition is the root of all my works. I lost my country. I lost my roots. And that pain, that irreparable loss, became my cinematic idiom.”

The impact of Partition in his cinema is not just in the narrative, but embedded deeply in his cinematic language. His jump cuts, grainy visuals, distorted sound, theatrical dialogues, and jarring music—all serve as metaphors for mental fragmentation.

When we talk about Ritwik’s cinematic language, his use of the camera deserves special attention. In Indian and even global cinema, he did not treat the camera as a mere recording device. Instead, he transformed it into a medium of inner consciousness, a reflection of the temporal shocks of history, and a vessel for the psychological turbulence of characters.

Ritwik’s camera often doesn’t just observe the external world, it penetrates the internal one. In Meghe Dhaka Tara, the way the camera follows Neeta’s psychological disintegration is unprecedented. Sometimes a tightly framed close-up, sometimes an abrupt extreme wide shot, this contrast gives his camera a unique psychological dimension. The backward camera movement and explosive sound during Neeta’s cry combine realism with the surreal. His shot compositions constantly remind the audience that this is more than just a visual.

Again, in Subarnarekha or Komal Gandhar, his camera trembles, shakes, as if reality itself cannot remain still under its own weight. War, Partition, refugee crises, his shattered realities are reflected in his use of shaky, hand-held shots. These become a philosophical reflection of an “uneven equilibrium.”

Ritwik was deeply influenced by Bengali theatre, especially the group theatre movement. His camera often mimics the stage and tracks the characters like a theatre spotlight. In Komal Gandhar, this theatrical consciousness is especially evident. The pan, track, and zoom of the camera moves rhythmically with dramatic expression. Often, one scene flows into another like segments of a stage play.

Music in a film is as important as the camera. Music is an inseparable part of cinema. In Ritwik’s films, folk songs and Baul music recur again and again. In Titas Ekti Nadir Naam, the folk songs of Brahmanbaria, pala gaan (narrative songs), and river-related tunes preserve the last breath of a vanishing culture. These songs do not emerge from the characters’ mouths—but seem to rise from the soil itself—a kind of cultural lament.

About the songs in his films, Ritwik once said:

“In Subarnarekha, most of the non-Bengali songs I used were ancient classical pieces. These are hardly used anymore today. The song ‘Aaju Ki Aananda’ in Raga Kalavati was taken from Abanindranath’s Rajkahini. I had a personal weakness for these, so I used them. I also used Rabindra Sangeet in this film. I have certain specific inclinations when it comes to music, and those found expression in this film.”

Using Raga Kalavati in Subarnarekha was a matter of personal taste. Take for example Bunuel’s famous ‘Nazarene’—a strikingly realist film. Except for the last one minute, there is no music at all. And in that last minute, only drum beats. The effect is extraordinary.

So why just mention Kalavati in Subarnarekha? In many great films of the world, like Fellini’s ‘La Dolce Vita’, the music “Patricia” was used to convey a very particular mood. Whether it succeeded or not, is for the audience and critics to judge.

The madman just walks around, spinning like a top. He has no home. No car. Neither did Ritwik. In all his films, he scattered a kind of native, homegrown long march, something like La Strada. Once he left home, he never stopped. Even Ramkinkar was made to walk through paddy fields, to show colours to the viewer. He kept dreaming of another home, even while walking. His companion was a child—both within and outside. Essentially, he devoted himself to a continual evolution, along which he met many other passionate seekers of rights, and with the ever-changing current of human civilization. Naturally, he had a dual nature.

Among Indian filmmakers, Ritwik Ghatak remains the only one who has fully delved into the indigenous, root-nurtured, emotionally resonant modes of storytelling, while embracing international, liberatory insights. This unadulterated thoughtfulness is the true touchstone of Ritwik’s greatness.

Writer Nabarun Bhattacharya once said in a speech:

“Once I had a quarrel with Ritwik over Jukti Tokko Goppo. I didn’t realise that day that I was talking to a Buddha. I had seen a Buddha all day and night.”

Note : Translated by Debamita Ghosh Sarkar

To read the original Bengali article , please click here :