Ghosts of Bengali literature – GetBengal story

“Bhautik bhitir mul shudhu pratyakkher agochar bastabkayahin sattar astitwa kalpanar hoyni. Praner nissongo ekakittwer moulik asohay bhitir moddhei er bij royechhe. …Nisshahay ekakittwer ahetuk bhiti ei-i bhuter bhoy prabriti anirdeshya atonker bij.”

(Golper Bhut / Sukumar Sen)

Bengali is a born chatterbox. When these three traits meet, they become unparalleled in relishing fear. Whether ghosts exist or not is a meaningless question, what is undeniable is the feeling of fear. And so, on a rainy monsoon evening over fritters, or on a wintry night while playing cards, Bengalis open the Pandora’s box of ghost stories. These tales always begin with solitude: the narrator stranded on a night of torrential rain, or at a deserted, remote railway station; or on the road, a haunted mansion—an old, windowless, doorless two-storied house overgrown with weeds, where the restless spirit makes itself felt through gathering shadows. Such space-time settings themselves are spooky—there may not even be a ghost.

In most Bengali ghost stories, the ghost often is not there at all, and even when it is, it is rarely harmful. Instead, ghosts tend to be emotional, helpful, almost relieved to chat for a while with humans.

Let me tell you one such story—our narrator, weak from fever, is advised by a doctor to seek a change of air. Wondering where to go, he ends up at Hasnuhana Cottage in Madhupur, owned by Sudhanshubabu, a friend of his father. The nameplate of the neglected house has lost its first three letters, so the house is now called Hanakuthi (House of Doom). It was built by Sudhanshu’s father, Sitanshu, who is now dead—a ghost, whose spirit is said still to guard the house. But though a ghost, he is not particularly dangerous. “A ghost, yet a truthful spirit! In some sense, a great soul.” When the narrator, knowing all this, chooses to stay at another house, Sitanshu’s spirit is offended—after all, the narrator is his guest. So in the middle of the night, he drags the narrator back to Hanakuthi. That is the archetypal Bengali ghost. (Modhupurer Hanakuthi /মধুপুরের হানাকুঠি ) by Himanish Goswami).

A second story, however, is not funny at all. The narrator is a medical student. During a trip to North India, the sister and aunt of one of his classmates die in a train accident. By chance, the corpse of that sister ends up at the medical college for dissection. It is the ghost of the aunt who reveals the corpse’s true identity to the narrator, because she wanted her niece to receive a proper funeral. (Mora Katar Bhoye /মড়া কাটার ভয়ে )by Mohonlal Gangopadhyay).

Thus, Bengali ghosts usually appear with very human qualities, their thoughts flow much like those of the living. They too are bound by social rules and rituals: they don’t haunt people on new-moon nights or on Tuesdays, and even have caste distinctions (Konkaler Tonkar/কঙ্কালের টংকার) by Monilal Gangopadhyay). They even have unions, where records are kept of who is good at frightening people and who is not. Some are forgetful (Bhulo Bhut /ভুলো ভূত )by Mahasweta Devi). Some were gossipy neighbours in life, who after death still cannot resist peeking into every household (Bhooter Masi Bhooter Pisi / ভূতের মাসি ভূতের পিসি by Purendu Patri). There are ghosts who, even after dying of malaria, do not forget their duties as a wife. She keeps on saving the husband from other spirits (Jamai / জামাই Manoj Basu). And so many more ghosts, countless in variety.

Bengali literature offers a wide diversity of ghosts: fish-loving ghosts, tree-dwelling ghosts, dancer ghosts, glutton ghosts, “bhembodattyis,” “shakchunnis,” “petnis.” Such figures are rare in foreign literature, because they are shaped by Bengal’s climate, society, and history. They are thoroughly Bengali ghosts.

Writers have used ghosts to do what ordinary humans could not, or to say artfully what was otherwise forbidden, often against the state. Thus, symbolic ghosts abound. Think of Tagore’s Korta’r Bhoot (Master’s Ghost), a concept of imperialist authority itself. Or Trailokyanath’s Lullu, who could question colonial change with boldness. Or Parashuram’s tales. Also consider one by Baidyanath Bandopadhyay—

During Pakistan’s war of independence, many Hindu Bengalis fled. In one such bordering West Bengal village, the spirit of a young girl saves refugees from the attacks of the rajakar militia and leads them safely across into Indian soil. The terror of death itself is no less than the terror of the supernatural. (Jibanta Putul/জীবন্ত পুতুল) by Baidyanath Bandopadhyay).

Manik Bandopadhyay’s ‘Pora chaya’ (পোড়া ছায়া ) is another such tale. In riot-torn Calcutta, the residents of a baro-ghar (a twelve-roomed building) are troubled by ghosts at midnight, an allegory for the mass displacement and uprooting caused by Partition. Here, ghosts are really the embodiment of those who suffered communal violence.

Human imagination about life after death is endless. Man has long sought to make life immortal, to rescue loved ones from death, or even cheat death itself, often through tantra, or appeals to dark forces. Bengali literature abounds with tantrics. Ashadevi’s Bisher Bansi (‘বিষের বাঁশি )is such a tale—in a secluded hilltop monastery lies a sealed chest containing the enchanted flute of a Buddhist tantric, with a deathly, mysterious allure. Bibhutibhushan’s Birja o Tar Radha (‘বিরজা হোম ও তার বাধা’ ) is also sucha a story where, through rituals, one attempts to snatch a fever-stricken girl from Yama, the god of death, but no one escapes him. There, the demon appears as:

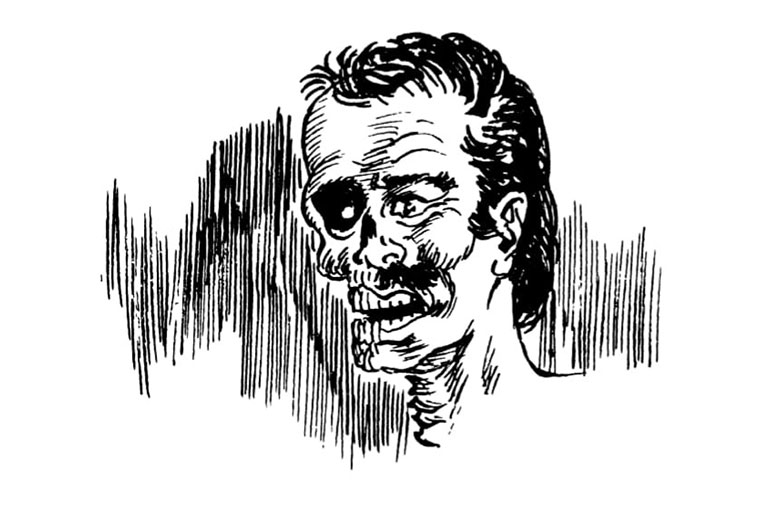

“পিছনের ছাদের কার্নিসের ওপর দাঁড়িয়ে এক বিরাটাকার অসুর কিংবা দৈত্যের তন্ময় মূর্তি। তার ততো বড়ো হাত-পা—সেই মাপে। মাথা একটা ঢাকাই জালার মতো। চোখ দুটো আগুনের ভাটার মত রাঙা, আগুন ঠিকরে পড়ছে। আমার দিকেই তাকিয়ে আছে অসুরটা। যেন আমাকে জ্বালিয়ে ভস্ম করে ফেলবে।”

(“On the roof cornice stood a gigantic demon or ogre, limbs in proportion to its size. Its head like a giant winnowing basket, eyes red as a furnace, blazing fire. Staring right at me—as if to burn me to ashes.”)

Bengali ghosts may have winnowing-basket ears, elephant tusks, legs like palm trees; they can stretch their limbs at will; they even cook rice by burning their own legs—so many things. Such images come directly from folklore, from the tradition of Indian fairy tales. Recently, Tumbbad (2018) stirred Indian horror cinema, where again, the primal-ghostly is shaped in the mould of fairy tales. Folklore ghosts often carry moral lessons, which is the essence of the Indian ghost.

In modern literature, however, foreign influences have reshaped the ghost’s form. Ghosts are now mostly bodiless, emissaries of death with supernatural power—inherently evil. Today’s readers perhaps prefer such tales. Yet, these too reveal many facets of the human mind. Even the eerie “ghostly cry” has changed—now sounding like an ordinary human voice.

The world changes, life changes, thus the framework of ghost stories is changing too. Yet let us not forget that the multifaceted ghost stories of Bengal are, at their core, stories of humanity itself.

Note : Translated by Debamita Ghosh Sarkar

To read the original Bengali article , please click here :

References:

Golper Bhut by Sukumar Sen, Ananda Publishers, 1982

Shatabdir Sera Bhuter Golpo, edited by Nanimadhab Choudhury