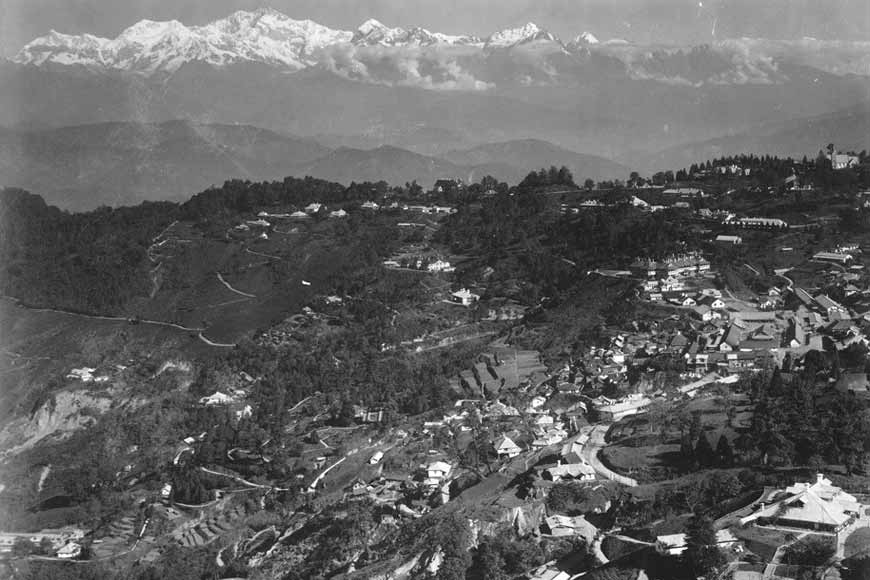

How Lord Bentinck helped in Birth & Growth of Darjeeling

We often visit Darjeeling, but how many of us know the story of a British General who chanced upon the ‘Queen of Hills’ and developed the area into the Darjeeling of today? GB brings you this 2-part series on the Birth of Darjeeling

Bentinck agreed to acquire the hill tract of Darjeeling as a military outpost and sanatorium, acknowledging that it also offered strategic advantages as a military outpost and trading hub. Captain Herbert, the Deputy Surveyor General, was then sent to Darjeeling to examine the area. The court of Directors of the British East India Company approved the project. General Lloyd was given the responsibility to negotiate a lease of the area from the Chogyal of Sikkim. The lease as per the Deed of Grant was granted on 1 February 1835. It said:

“The Governor-General having expressed his desire for the possession of the hills of Darjeeling on account of its cool climate, for the purpose of enabling the servants of his Government, suffering from sickness, to avail themselves of its advantages, I the Sikkimputtee Rajah out of friendship for the said Governor-General, hereby present Darjeeling to the East India, that is, all the land south of the Great Runjeet river, east of the Balasur, Kahail and Little Runjeet rivers, and west of the Rungpo and Mahanadi rivers.”

“The Governor-General having expressed his desire for the possession of the hills of Darjeeling on account of its cool climate, for the purpose of enabling the servants of his Government, suffering from sickness, to avail themselves of its advantages, I the Sikkimputtee Rajah out of friendship for the said Governor-General, hereby present Darjeeling to the East India, that is, all the land south of the Great Runjeet river, east of the Balasur, Kahail and Little Runjeet rivers, and west of the Rungpo and Mahanadi rivers.”

In 1841 the British government granted the Chogyal of Sikkim an allowance of Rs. 100,000 per annum as compensation and raised the grant to Rs. 6,000 per annum in 1846. Dr. Campbell brought Chinese tea seeds in 1841 from the Kumaon region and started growing tea on an experimental basis near his residence at Beechwood, Darjeeling. This experiment was followed by similar efforts by several other British planters. The experiments were successful and soon several tea estates started operating commercially.

The rapid growth of Darjeeling led to jealousy from the Chogyal of Sikkim. There were also differences between the British Government and Sikkim over the status of people of Sikkim. Because of the increased importance of Darjeeling, many citizens of Sikkim, mostly labourers started to settle in Darjeeling as British subjects. The migration disturbed the feudal lords in Sikkim who resorted to forcibly getting the migrants back to Sikkim. Relations deteriorated to such an extent that when Dr. Campbell and explorer Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker were touring in Sikkim in 1849, they were captured and imprisoned. This detention continued for weeks. An expeditionary force was sent by the East India Company to Sikkim. However, there was no necessity for bloodshed and after the company's troops had crossed the Rangeet River into Sikkim, hostilities ceased.

Consequent to this trouble, and further misconduct on the part of the Sikkim authorities a few years later, the mountain tracts now forming the district of Darjeeling became part of the British Indian Empire, and the remainder of kingdom of Sikkim became a protected state. The area of Kalimpong along with the Dooars became British property following the defeat of Bhutan in the Anglo-Bhutan war (Treaty of Sinchula – 11 November 1865). Kalimpong was first put under the Deputy Commissioner of Western Dooars, but in 1866 it was transferred to the District of Darjeeling giving the district its final shape.

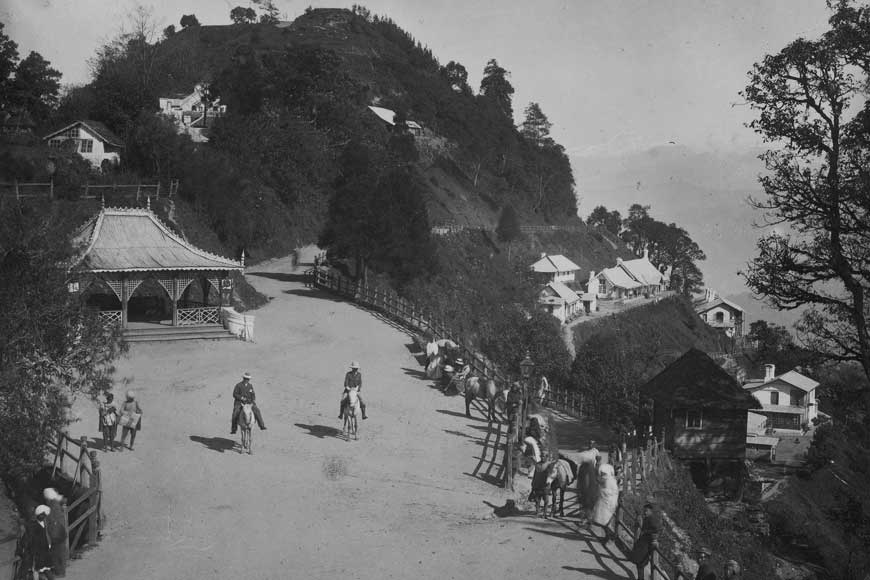

The Darjeeling Municipality was established in 1850. Tea estates continued to grow. By the 1860s, peace was restored along the borders. During this time, immigrants, mainly from Nepal, were recruited to work in the construction sites, tea gardens, and other agriculture-related projects. Scottish missionaries undertook the construction of schools and welfare centres for the British residents: Loreto Convent in 1847, St. Paul’s School in 1864, Planters’ Club in 1868, Lloyd’s Botanical Garden in 1878, St. Joseph’s School in 1888, Railway Station in 1891, and Town Hall (present Municipality Building) in 1921. With the opening of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway in 1881, smooth communication between the town and the plains below further increased the development of the region.

Darjeeling Municipality took responsibility for maintaining the civic administration of the town as early as 1850. From 1850 to 1916, the municipality was placed in the first schedule (along with Halna, Hazaribagh, Muzzaferpur and others), where commissioners were appointed by local governments and second schedule (along with Burdwan, Hooghly, Nadia, Hazaribagh and others), where the local government appointed a chairman.

Prior to 1861 and from 1870–1874, Darjeeling District was a "Non-Regulated Area" (where acts and regulations of the British Raj did not automatically apply in the district in line with rest of the country, unless specifically extended). From 1862 to 1870, it was considered a "Regulated Area". The term "Non-Regulated Area" was changed to "Scheduled District" in 1874 and again to "Back Ward Tracts" in 1919. The status was known as "Partially Excluded Area" from 1935 until the independence of India.

Source:

Urban Management in Darjeeling Himalaya: A Case Study of Darjeeling Municipality.

Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj by Kennedy, Dane Keith

Bengal District Gazetteers: Darjeeling, Government of Bengal (archive.org)