Jogesh Dutta and his silent, universal art

On the evening of August 9, 2009, in front of a packed house at Rabindra Sadan auditorium, Jogesh Dutta finished his act titled ‘The Thief’, came out onto the stage, laid down his wig and costume on the floor, and took his last bow. True to his profession, he didn’t say a single word to the audience. And that was the last time India’s pioneering mime artist appeared in a public performance. He was 76, and for over 50 years, had single-handedly established mime as an art form in India.

As a young man in the mid-1950s, Dutta was beginning to make a living as a stand-up comic when, on a visit to the Lake (Rabindra Sarobar), the sight of courting couples gave him his first idea of a mime act, and thus was born his famous routine of a woman putting on makeup, sitting at a dressing table.

Today, sitting in his flat in a south Kolkata highrise, his compact yet frail 86-year-old body still erect despite the walking stick he carries, in a voice that barely rises above a whisper, the legend looks back to that evening without a trace of regret. “Everything has its proper time. Just as a cricketer or footballer has to go when his body no longer allows him to play, so a performer has to know when he can no longer serve his art,” he says, in his typically gentle, reticent voice.

As a young man in the mid-1950s, Dutta was beginning to make a living as a stand-up comic when, on a visit to the Lake (Rabindra Sarobar), the sight of courting couples gave him his first idea of a mime act, and thus was born his famous routine of a woman putting on makeup, sitting at a dressing table. “While observing the couples, I realised that though I couldn’t hear their words, from their body language alone, I could tell which of them were married to each other, or not married, or even adulterous,” he says. “So I thought, why not try and portray emotions and actions without speaking?” Unknowingly, he had stumbled upon the ancient art form of mime.

The preceding years had been hard ones for the young man who, as a mere 12-year-old, had lost both parents within 10 days of each other, having arrived in Kolkata as refugees from post-Partition East Pakistan. Having found shelter in the home of relatives in Salkia, the boy found himself yearning to get out. “I came from a poor family, and the affluent relatives I was living with had a lifestyle completely different from what I was used to. People would eat sitting at table instead of on the floor, the women of the family didn’t cook, it was all done by servants. I was bewildered by all of this, so I ran away,” he says, with a trace of a smile.

Finding his way to Howrah station, the boy spent the night sleeping in a stationary train. When he awoke, it was moving. Someone told him it was the Bhagalpur Express, before the ticket examiner came aboard and evicted him at Rampurhat station. It was here that he spent the next few months, working at a tea stall owned by one Ram Bahadur. A few more hard knocks from life later, he was found by his elder brother and taken back home, having stayed away for three years.

These early experiences may not have found their way into his acts, but they shaped the tone of his art - a serious message delivered through apparent comedy. The performance of mime originates at its earliest in ancient Greece; the word ‘mime’ itself comes from Greek ‘mimos’, meaning ‘imitator, actor’. However, India has its own mime tradition, dating back almost 3,000 years to the seminal text ‘Natya Shastra’, where it is termed ‘mukabhinaya’ (mute acting). That makes Indian mime different in tone and tenor to the European mime tradition. In the modern era, mime has come to mean a person who uses the language of the body as a theatrical medium or performance art, without speech. And that makes it universally identifiable. Unlike the spoken word, non-verbal actions require no subtitles or translations.

Much of what Dutta feels about his art is encapsulated in ‘Mukabhinayam’ (1993), a book which he edited and contributed a piece to, titled ‘Commedia dell’arte’.

When Dutta started out, he knew none of this. Indeed, when legendary French mime Marcel Marceau first visited Kolkata in the early 1960s, the young Jogesh couldn’t afford the money to buy a ticket for the performance at New Empire cinema, but he has no regrets. In fact, he is glad he was deprived that day. “Who knows, I may have become so influenced by him that my own style would never have developed,” he says. Instead, he drew inspiration from the likes of Uday Shankar, Bala Saraswati, Gopinathan Pillai (famed as Guru Gopinath), and even Indian temple art for his routines. “Their art helped me form a distinctly Indian mime tradition,” he says.

Ironically, many years later, Dutta himself was instrumental in bringing Marceau back to Kolkata, organising performances at Rabindra Sadan, Rabindra Bharati University, and Jogesh Mime Academy. Marceau even held workshops with Dutta’s students at the academy. “He told me, it is no surprise that India has a mime tradition. You already have Kathakali and Bharatanatyam anyway,” smiles Dutta reminiscently.

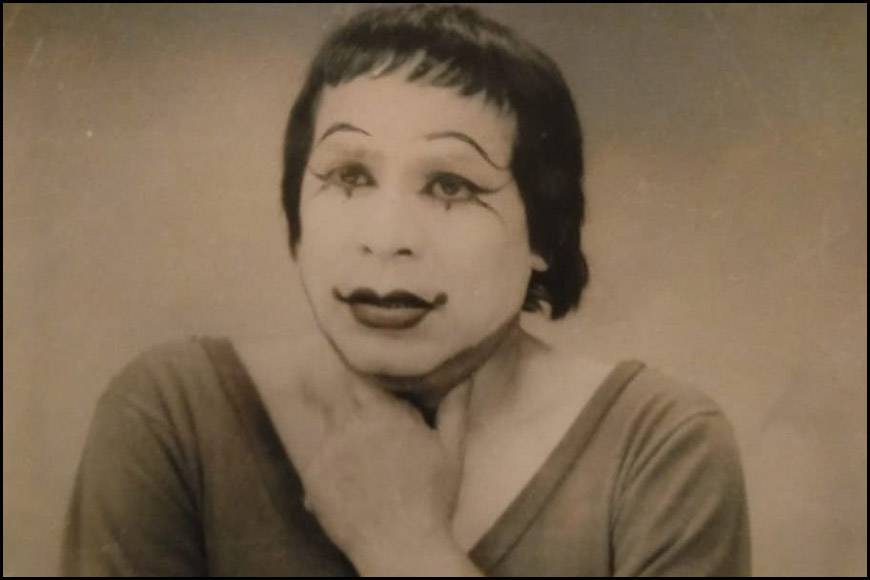

Much of what Dutta feels about his art is encapsulated in ‘Mukabhinayam’ (1993), a book which he edited and contributed a piece to, titled ‘Commedia dell’arte’. The book also contains essays by several icons of Bengali cinema and stage, among them Khaled Choudhury, Tapas Sen and Ananta Das, all three of whom also played crucial roles in Dutta’s career. The distinctive makeup he wears was in part inspired by the Kathakali tradition, where the eyes are highlighted so that their every little movement can be seen from the first to the last row of an auditorium, says Dutta. “Ananta Das (Satyajit Ray’s legendary makeup artist) helped me get it right,” he adds, momentarily crinkling up his eyes to demonstrate his point. For a split second, the artist emerges from within the quiet, self-contained octogenarian.

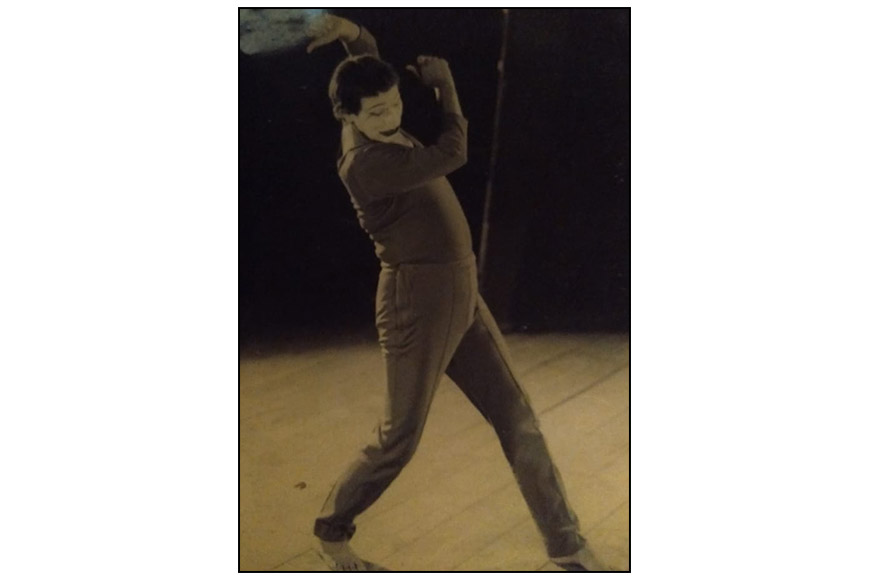

The costume he wore was designed by renowned art director Khaled Choudhury, its tightness enhancing every line of his body, since his art is all about body language. The lights for his initial performances were designed by the iconic Tapas Sen, who recognised the need for a completely different stage illumination for a mime act. And the music was done by none other than V. Balsara.

Also read : Decorated war hero of the Indo-China War 1962

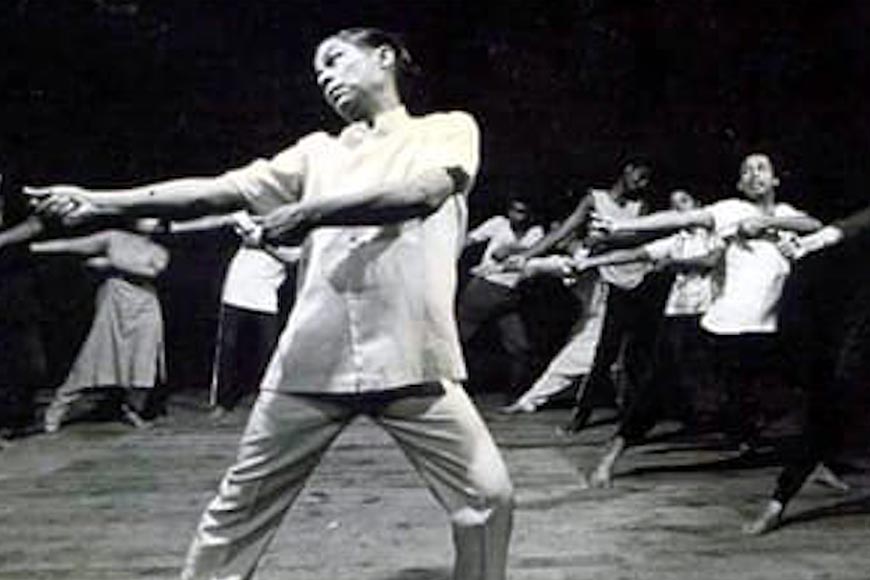

Having spent a lifetime traveling around the world, performing and teaching mime, Dutta today looks back with some satisfaction to the time when Rabindra Bharati approached him to join their faculty, and the University Grants Commission approved of mime as an academic discipline. His students are now scattered all over the country and the world, propagating his art to students of their own.

With childlike delight, he recalls the first time he was on a plane in 1960, travelling to Falakata airfield in North Bengal for a performance, scooping up candy from the tray held out by a stewardess once he realised it was free. “I have been on countless flights since then, but the excitement of that first flight, the public performance at Falakata where people took my autograph for the first time, these are things I have never forgotten,” he says. “Whatever happened after that was a bonus.”

Having spent a lifetime traveling around the world, performing and teaching mime, Dutta today looks back with some satisfaction to the time when Rabindra Bharati approached him to join their faculty, and the University Grants Commission approved of mime as an academic discipline. His students are now scattered all over the country and the world, propagating his art to students of their own.

This sense of serene satisfaction was perhaps what helped him retire at the height of his fame and popularity. And it has helped him stay away, despite repeated requests for a comeback. All his life, he has steadfastly refused help from the government, except the initial grant of a little over 4,000 sq ft of land in 1970 for his academy near Hazra crossing. Even the academy was built using money raised through crowd-funding. “I was granted the land without asking for it, but have never sought any help other than that,” he says firmly.

As our conversation winds up, he volunteers, “When I started the academy, I realised that my art needed to be protected, because it had no grammar, no mathematics. It needed to be established and taught. Today, I know my art will never be lost.”