‘Nehru was noncommittal when I asked for Indian citizenship’

This year, March 13 marked the 25th year of the death of Emilie Schenkel, the Austrian wife of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, and mother to their only child, Dr Anita Bose Pfaff. Dr Bose-Pfaff’s reminiscences about her late father, who died when she was about three, form the basis of a series of monthly conversations aired on YouTube titled ‘The Anita Dialogues’ conducted by Sampriti, an organisation of Bengalis in Germany, in honour of the 125th year of Netaji’s birth. The current president and founder of Sampriti, Shaibal Giri, has moderated this historical conversation series, in which several untold stories, anecdotes have already come up and will also be shared in the upcoming episodes for the millions of Netaji followers spread all over the world.

The first episode of the series featured Netaji and his aide Abid Hasan’s daring escape on a German U-180 submarine or U-Boat bound for the Far East in February 1943. In the second episode, premiered on March 14, the topic is the landmark event from March - the Tripuri session of the Congress in 1939, when Netaji was elected Congress President over the objections of Mahatma Gandhi. The episode also features two internationally renowned historians, Prof Leonard Gordon and Dr Rudranshu Mukherjee, as guests.

Much of Bengal and its people’s “ambivalence” towards Gandhi, as Gordon puts it, can probably be traced back to the Tripuri Congress, for which Netaji put forward his candidature in the certain knowledge that he would be opposed. This, despite the fact that in 1938, Gandhi had reluctantly agreed to Netaji’s nomination for a second term, since Jawaharlal Nehru had already served two terms.

Gandhi’s reluctance to accept Subhas as a candidate post the Haripura Congress in 1938, because Gandhi had made it very clear that Subhas was “not dependable”. Caught between Gandhi and Bose was Nehru, though Mukherjee’s theory is that the push to sideline Subhas was probably coming from the likes of C. Rajagopalachari and Vallabhbhai Patel, with whom Netaji had had a major fallout over the last will and testament of Vallabhbhai’s elder brother Vithalbhai, who had left a large sum of money to Netaji, to be used to further the freedom movement.

As Gordon quotes from one of his books, the astute and vastly experienced Gandhi perhaps understood Subhas better than he himself did, and in every communication starting from the election to the end of April, Gandhi was making it clear that if Subhas did not have a concrete plan of action, or enough support within the Congress, he should “get out of the way” and let “Patel & Co” get on with Gandhiji’s programme.

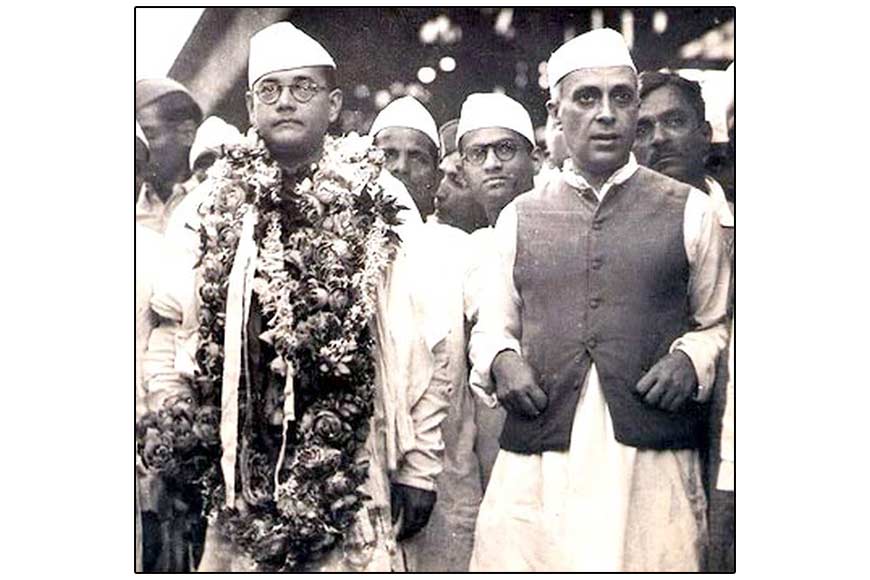

Nehru and Netaji

Nehru and Netaji

Dr Mukherjee further highlights Gandhi’s reluctance to accept Subhas as a candidate post the Haripura Congress in 1938, because Gandhi had made it very clear that Subhas was “not dependable”. Caught between Gandhi and Bose was Nehru, though Mukherjee’s theory is that the push to sideline Subhas was probably coming from the likes of C. Rajagopalachari and Vallabhbhai Patel, with whom Netaji had had a major fallout over the last will and testament of Vallabhbhai’s elder brother Vithalbhai, who had left a large sum of money to Netaji, to be used to further the freedom movement. Vallabhbhai refused to accept this will, and an unseemly legal dispute ensued.

Not only did Vallabhbhai eventually win the case, but he secured assurances from “every possible legatee” of that will that they would not accept a single rupee from the estate of Vithalbhai, says Mukherjee. This was a source of huge disappointment for Subhas, added to the fact that Vallabhbhai never politically supported him anyway. Meanwhile, Nehru was as fond of Subhas as he was loyal to Gandhi, but he was constantly advising Gandhi to settle the dispute with Subhas because “we cannot afford to have him leave the Congress at this time”. Simultaneously, he was also corresponding with Subhas, and their discourse was occasionally acrimonious, with Subhas writing a typed 27-page letter to Nehru at one point. Eventually, when Subhas asks him for a one-to-one meeting, Nehru makes a most important remark, according to Mukherjee: “I cannot say no to Subhas.”

The episode is full of many more such insights, with Mukherjee pointing out how the Tripuri episode paints Gandhi “at his worst”, and how his refusal to help Netaji in the matter of forming a working committee pushes the latter into a corner, because a resolution had been passed that any working committee must have Gandhi’s endorsement. Significantly, when Netaji resigned as president in 1939 just prior to the Calcutta Congress, the sole dissenting voice was that of Nehru, who was vocal in his opinion that the resignation must not be accepted, Mukherjee says.

Nehru was as fond of Subhas as he was loyal to Gandhi, but he was constantly advising Gandhi to settle the dispute with Subhas because “we cannot afford to have him leave the Congress at this time”. Simultaneously, he was also corresponding with Subhas, and their discourse was occasionally acrimonious, with Subhas writing a typed 27-page letter to Nehru at one point. Eventually, when Subhas asks him for a one-to-one meeting, Nehru makes a most important remark, according to Mukherjee: “I cannot say no to Subhas.”

Why was Gandhi so opposed to Netaji? Gordon feels one reason was Gandhi’s awareness that Subhas retained his ties to the militant revolutionary groups of Bengal, and could never be “100 percent Gandhian”. The issue was very much one of control, adds Mukherjee, with the Pant Resolution describing Subhas’ programme as “a leaky boat”. And yet, as Mukherjee also points out, on Azad Hind Radio, which began broadcasting from Nazi Germany in 1942 under the leadership of Subhas, it was Subhas, and not any apparent Gandhian loyalist, who described Gandhi as “father of the nation” for the first time.

Despite the eventual separation between Nehru and Subhas, it has been well documented that when Nehru heard of Subhas’ possible death in the Taihoku air crash, it was one of the rare occasions when he allowed himself to weep in public, as he would for a younger brother, which is how he viewed Subhas.

Anita adds her own interesting take to this relationship, saying how warmly Nehru received her when she first visited India in 1961, though he was noncommittal in his response when she asked him if she could get Indian citizenship. She says it was the “Nehru-Gandhi clan” which followed Nehru who sought to perhaps downplay her father’s contribution to the freedom struggle.

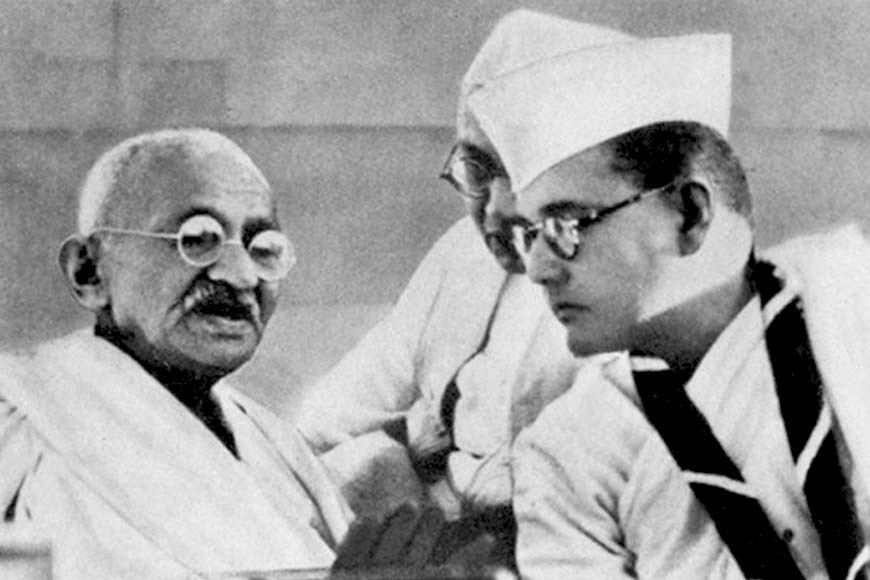

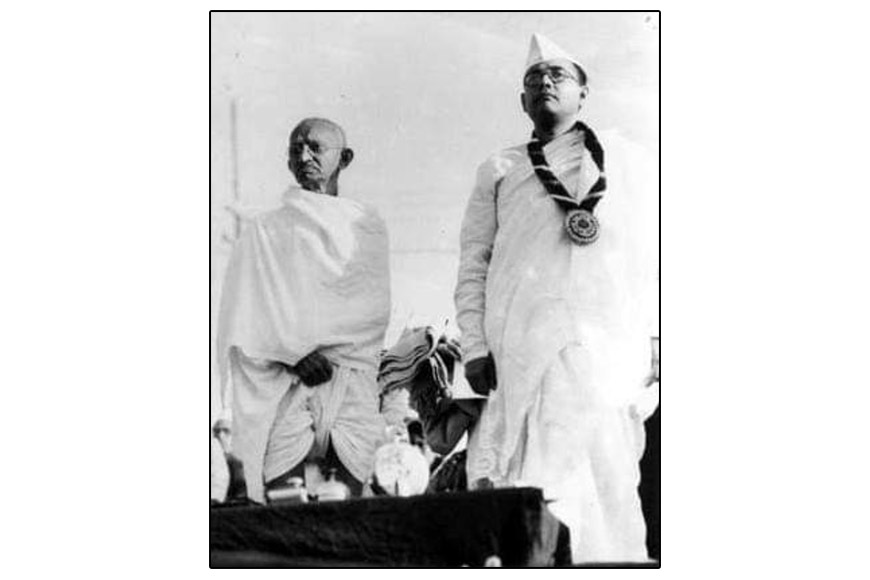

Subhas Bose with Gandhiji

Subhas Bose with Gandhiji

Why was Gandhi so opposed to Netaji? Gordon feels one reason was Gandhi’s awareness that Subhas retained his ties to the militant revolutionary groups of Bengal, and could never be “100 percent Gandhian”. The issue was very much one of control, adds Mukherjee, with the Pant Resolution describing Subhas’ programme as “a leaky boat”.

Also making its way into the discussion is the way Gandhi, and later the British, blocked the Fazlul Hoque-Sarat Bose alliance to form Bengal’s provincial government, with Mukherjee referring to Gordon’s book to point out how both Subhas and Sarat had their “health broken” in British prisons.

Next month’s episode is scheduled to feature Asha Sahay, a former lieutenant colonel of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, and the daughter of late Anand Mohan Sahay, a prominent member of the Azad Hind Fauj, who will talk about Subhas Bose’s re-entry into India post his submarine adventure.