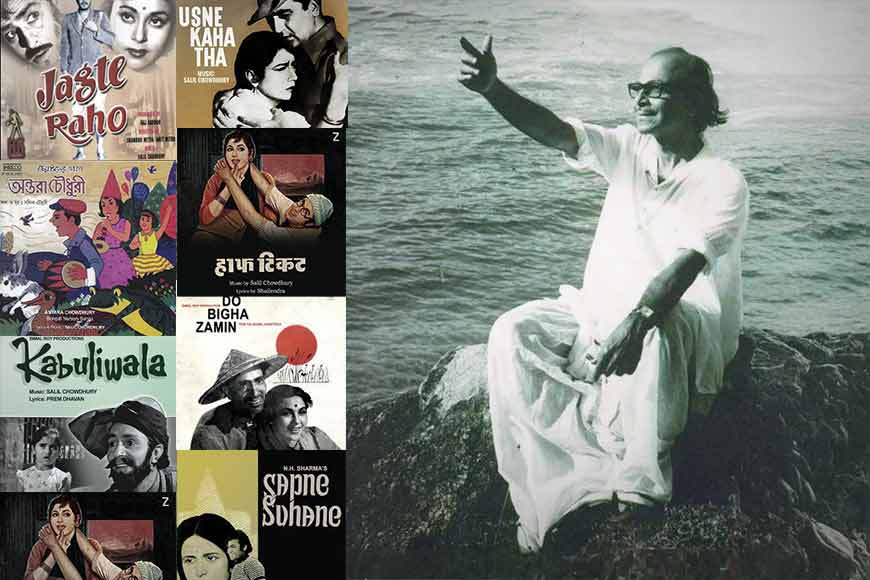

Salil Chowdhury marks his centenary : The timeless composer who bridged Bengal, Kerala and the World through his music - GetBengal Story

In 2025, Salil Chowdhury turns 100. Yet, even today, he remains “Salil da” to Kerala’s younger generation. In an age when forgetfulness has become a habit, how does he remain so alive in people’s hearts? The answer comes from V.S. Shyam, a thirty-something IT professional from Kochi and a well-known space enthusiast. For him, Salil Chowdhury isn’t just a composer—he’s a lifelong companion.

Kerala’s Cultural Icon

Even today, Salil Chowdhury is a cultural icon in Kerala. Generation after generation, the man from 24 Parganas continues to embody the emotions of this southern state. His songs are timeless—and deeply universal. Several fan clubs still exist in his name. Through melodies that spoke of golden harvests, village brides, and the rhythm of rural joy, Salil united Bengal and Kerala in music.

During Onam, playlists often feature “Poovali Poovali Ponnamari,” Salil’s festive song that heralds the season—just as Durga Puja in Bengal feels incomplete without his “Ay re chute ay, pujor gondho eshechhe…” The imagery of “Poovali Poovali” recalls the revolutionary Salil, the voice of the peasant movement.

The Revolutionary Salil

In the 1940s, while still a university student, Salil was irresistibly drawn into progressive social movements. In 1945, he joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). A native of the 24 Parganas district, his cultural activism began through the peasant movement. Working across the Kolkata and 24 Parganas branches, he immersed himself in the lives of the poor and suffering. His personal struggles, pain, and uncertainty blended with their stories.

He first played the flute, and in 1946, inspired by the Tebhaga movement, wrote “Hey Samalo.” For flood victims in Sonarpur, he composed “Desh bheshechhe baner jole.” That same year, on July 29, celebrating the success of a nationwide strike, he penned “Dheu uthchhe, kara tutchhe.”

Also read : Anatara Chowdhury speaks on Salil Chowdhury

Songs, Poetry, and Stories

His first recorded song was “Nandito Nandito Desh Amar,” based on Raga Nabarun, which became immensely popular. His compositions of the 1940s became the highlights of IPTA gatherings, making him a household name among Communist workers across Assam and Bengal. Alongside his music, he wrote poems and short stories—among them “Rickshawala” and “Ei Gaayer Bodhu.”

The story of a landless farmer who becomes a rickshaw puller later transformed into the film “Do Bigha Zameen.” In Salil’s own words, it was “the first Indian film about agrarian life and the struggles of day labourers.” The film achieved international acclaim.

In 1949, in newly independent India, Hemanta Mukhopadhyay sang “Kono Ek Gaayer Bodhu,” composed by the young Salil Chowdhury. The song broke every record in Bengali modern music. Both the Gramophone Company and the barely twenty-year-old Salil became overnight successes.

He reimagined Tagore’s “Krishnakali” in the context of the Bengal famine, creating “Sei Meye.” Songs like “Bicharpoti,” “Runner,” and countless others followed—each a masterpiece.

The Father Behind the Legend

Behind all this stood his father, Dr. Gyanendra Chowdhury, a bold doctor in the tea gardens of Lata Bari, Assam—and an ardent lover of Western classical music. During Durga Puja, he organized plays with the tea garden workers. His vast collection of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven records created the musical atmosphere that shaped Salil’s ear.

Salil’s first experience conducting music came while assisting his father. Evenings in Assam were filled with music at their home, led by Dr. Chowdhury’s senior compounder, Sukumar Babu. Together they recreated the songs of Bengali cinema—Mrinallkanti Ghosh, Krishnachandra Dey, Kamala Jharia—on the harmonium. Without realizing it, Salil’s father had sown in him the seeds of both a cultural revolutionary and a composer.

The University of Music

Salil encountered a wealth of cultural expressions across India - musical tunes and forms and styles of singing - and it became his real university. His music encapsulated Bengal, the Dravidian South, and Maharashtra. However, overall, it was about humanity.

He experienced the pains of partition, the violence of riots, wars and famines and it shaped his artistry. Music, poetry and writing were not ever something Salil purely enjoyed or entertained himself with. They were means of expression, and freedom. He wrote in 14 Indian languages.

His iconic collection of protest songs, “Ghum Bhanga’r Gaan”, was released in the 1980s. On the record cover, he wrote:

“Though composed in different social, economic, and political contexts, the inspiration behind these songs is mankind’s eternal struggle for freedom—from all forms of bondage, oppression, and exploitation. That very struggle has, through ages, given humanity the courage to face bullets and the noose.”

The Eternal Salil

Salil Chowdhury is, and will always remain, Salil Chowdhury. His songs are his identity—no adjective before his name can truly capture his greatness. He once wrote, “Ei sarata desh jure amar ghar bari…” . Indeed, his home still lives on—in every listener’s heart. Time may change, but hearts never replace the space he occupies.

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here.