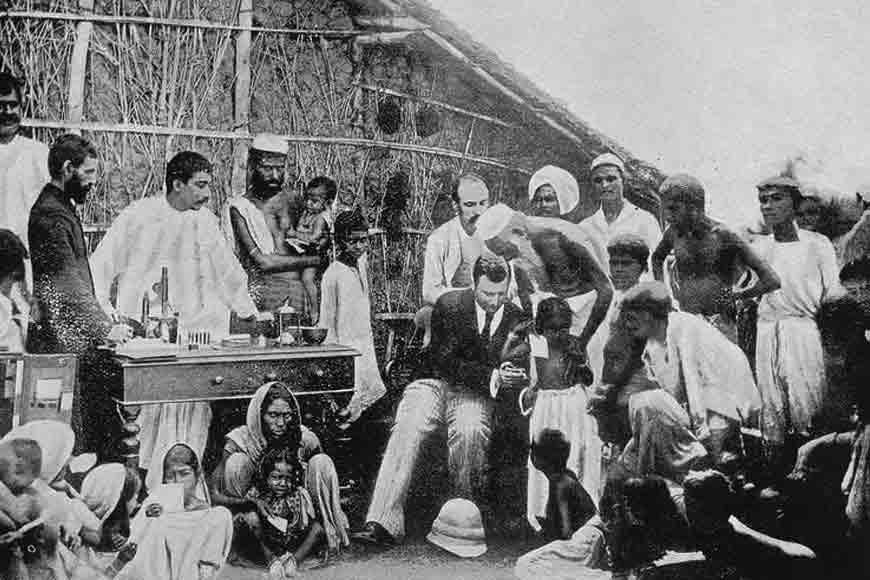

Vaccination during colonial time

The reports indicate that British India was carved into separate regions such Bengal, Madras, Burma, Punjab etc as per their importance with a sanitation team led by a Sanitary Commissioner and supported by a staff of superintendents, inspectors and vaccinators to carry out this vaccination programme. In Bengal, the British created ‘Protective Circles,’ a system of protective barriers around the periphery of Calcutta. Dr T Edmonton Charles aimed to vaccinate all within that set circle. Originally, there were around seven such circles in Calcutta, protecting the city as it was surrounded by vaccinated areas.

In 1867, a man travelling to Calcutta contracted smallpox and died on the periphery of the city. Because the area had been mostly vaccinated, the spread of the disease was successfully contained. This is indeed interesting as to how the British ensured the safety within the vaccinated circles. Superintendents and their direct insubordinates tended to be either British or in the employ and trust of the British Colonial Service as displayed in the reports. Titles such as Surgeon Major, Captain, Lieutenant Colonel and Dr often precede a list of credentials, including the Indian Medical Service (IMS). However, the vaccinators and often their direct supervisors tended to be locals to the area. The reports unveil that vaccinators who travelled out or worked in the dispensaries would be both a hindrance and saviour for the vaccination program. The British doctors planned introduction of vaccine institutes in Bengal, Madras and Punjab separately. Within these establishments, tests were completed on the best way to synthesize and maintain the cowpox to allow it to be dispatched to the vaccination teams. Interestingly, the vaccinators who were mainly locals, were paid very low wages and this was noted by the Sanitary Commissioner in 1913-1914 as potential reasons for poor service.

Low wages also caused problems, not simply in the perceived ineptitude of the vaccinators but in the retaining of staff: they either vacated their position or were dismissed. In the Darjeeling Circle in Bengal in 1878 an instance of strike by vaccinators against the low pay saw the loss of nearly the whole vaccination team through dismissal or absconding. To overcome this problem and the increasing concern of a non-vaccinated poorer population, pockets of free vaccination arose. An example of this was in Bengal, which saw an immediate increase in vaccination in areas where it was free.

In 1867, a man travelling to Calcutta contracted smallpox and died on the periphery of the city. Because the area had been mostly vaccinated, the spread of the disease was successfully contained. This is indeed interesting as to how the British ensured the safety within the vaccinated circles. Superintendents and their direct insubordinates tended to be either British or in the employ and trust of the British Colonial Service as displayed in the reports.

The Vaccination Act of 1880 of Bengal outlawed inoculation and made it increasingly compulsory for children to be vaccinated. The reports reveal that the Act was continually updated and that similar legislation spread to other Indian regions. Dr Edmonston Charles in 1867 highlighted the lack of legislation at the time as a lack of recognition for the severity of the prevalence of smallpox in the Bengal region. Suspicions about British vaccination led to rumours in Bengal fearing that the British were deliberately infecting locals with plague! Religion and inoculation would join forces, as shown by a woman apparently possessed by the Goddess Sitala in 1864 in Bengal: '… she … amid incoherent ravings denounced the vaccinators and prophesised that everyone they operated on would die; only three vaccinations were done that year.' ('Report on the vaccinator proceedings throughout the government of Bengal'|)

The Vaccination Act of 1880 of Bengal outlawed inoculation and made it increasingly compulsory for children to be vaccinated. The reports reveal that the Act was continually updated and that similar legislation spread to other Indian regions. Dr Edmonston Charles in 1867 highlighted the lack of legislation at the time as a lack of recognition for the severity of the prevalence of smallpox in the Bengal region.

Yet the vaccinators were not against using this religious slant to their advantage. The following year the same woman claimed that the Goddess had sent her permission for the vaccinators to practice their trade. A similar incident in the same year outlines another possession which drove a women to declare publicly '… that the vaccinators were commissioned by the Goddess to cure smallpox and … and that the people should accept their services.' ('Report on the vaccinator proceedings throughout the government of Bengal')

The British considered their programme to reduce the devastation of smallpox to be so successful that British attention in Bengal, for example, by 1929 had shifted from smallpox to other diseases such as malaria, cholera and fever. We all hope like the British centuries ago, India will go through an effortless COVID-19 vaccination programme.