AGOMONI – Durga Puja is about ‘Inclusiveness.’ Artisans of every caste has a task

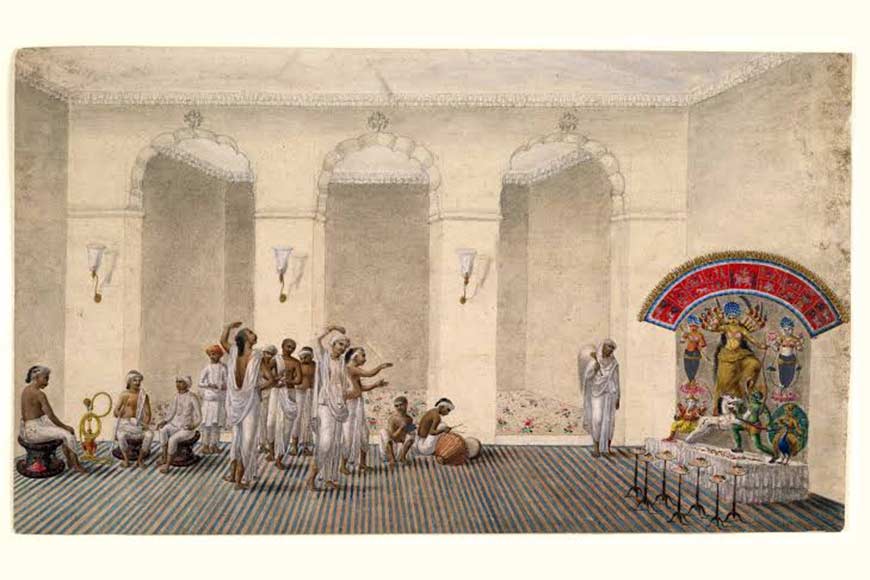

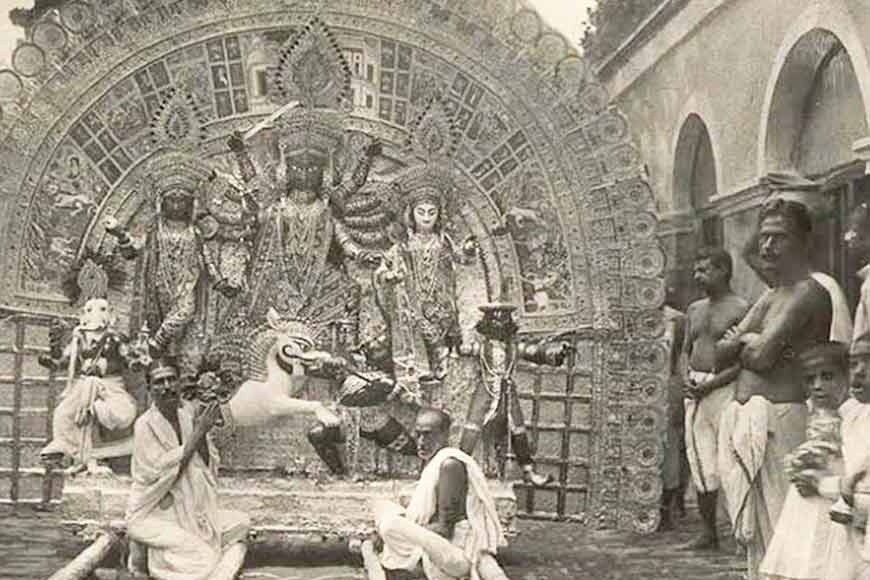

Can you imagine Durga puja without plates and dishes made of clay for offerings, or designs of shola adorning the idols, copper utensils displayed, or even a pandal without a chandoa (shamiana), an idol without a wooden framework? Well, the answer is a big ‘No.’ But have you ever wondered who all are involved in the multiple tasks that go in to supply all these minute details of an elaborate festival? During the times of zamindars, different sections of the society were assigned various artistic work. From the lowest strata to the highest in a caste and class based Indian society, Durga Puja was and still is, one festival that has exhibited values of an inclusive form. Bengal’s indigenous art and craft forms essential for Puja preparations, made it possible to involve every strata of craftsmen and workmen, from Dom to Kumor, from an idol maker to a coppersmith and cobbler. Durga Puja of Bengal is thus not just a festival, but a celebration of an inclusive society.

Bengal’s distinct and unique socio-cultural identity has been shaped by its geographical location and environment, factors instrumental in formulating exclusive customs, beliefs and rituals of indigenous Bengalis. Take for example forms of God, that have been presented as a distinct identity in Bengal, in sharp contrast to the way they are worshipped in other parts of India. Shaivism, or Saivism, is one of the most popular Hindu cults and Lord Shiva is the presiding deity of this sect. He symbolizes ‘the connection between religion and art form.’ He is the lord of dance, music and drama, encompassing creation, destruction and everything in between.

The Nataraja iconography incorporates contrasting elements, a fearless celebration of the joy of dancing, while being surrounded by fire, untouched by forces of ignorance and evil, signifying a spirituality, that transcends all duality. However, in Bengal, Shiva gets a makeover. He does not represent any of the above-mentioned divine qualities. Instead, his portrayal is based on Mangal-Kavya and he turns a rustic simpleton, bereft of cosmic and philosophical qualities. Shiva as depicted in Bengal’s folk-songs, is a drifter, who would beg rather than work and possess no sense of social responsibility. He is the son-in-law, married to Giriraj’s daughter, Uma. Uma pays her annual visit to her parents’ abode with her children and after a short stay, returns to her husband’s home.

Durga Puja in Bengal thus turns into a magnified celebration of a daughter’s visit to her parents’ home. Hence, we find intricate rituals that concentrate on pampering and pleasing the precious daughter who is no more a member of the family, but a temporary guest at her maternal household. Thus, every attempt is made to make her stay as comfortable and joyful as possible. She is gifted new attire and jewelry, served a variety of food items that she loves. She is offered dozens of sarees and betel leaf, so that she can pick and munch on them. Elaborate arrangements are made to entertain her and she is not alone to enjoy this hospitality. It is extended to her entourage of four children, who again have individual tastes and myriad demands.

Extensive planning for Uma’s mega-visit starts well in advance. The nitty-gritties of preparations are quite elaborate and time-consuming and the presentation is aesthetically beautiful and functionally perfect. In the village-centric culture of Bengal, it was pertinent to start acquiring articles and items needed for her worship, months before the actual festival began. Topping the list, was a combination of herbs and rare fruits, scouted from the vicinity. Items collected got a makeover from artisans specialized in vocational streams, to make the offerings aesthetically pleasing. Somewhere down the line, craftsmen and their vocation thus became an integral part of Durga Puja rituals.

In areas where firewood was not easily available and villagers had to go to nearby jungles to procure wood to keep their hearth burning, shoots and trunks of Babla tree (thorny acacia) were gathered, for performing Yajna. This year-long search culminated during Durga Puja. The monotony of these long and arduous journeys would be interspersed with a leisurely puff of the hookah. This tradition continues even today. Tobacco leaves and accompanying ingredients are mixed with jaggery and pounded in a husk lever (dhenki), long before Puja preparations begin. The compound is then put in an urn full of jaggery. A pungent smell emanates from the urn after roughly three weeks, a sign that the tobacco is now ready for the hookah connoisseur. A lighted earthen plate (malsha) is usually left in a corner of the pandal. When artisans take a break, they pick up the hookah for a puff or two. The demand for these malshas go so high before the Pujas, that potters increase the number of clay plates they make. The potter wheels run non-stop, churning out endless number of kolke as well. A Puja-centric industry thus springs up in the potter ghetto months before the actual puja starts.

The sweeper community (dom para), representing the lowest rung of the social frame also contributes in myriad ways and becomes an intrinsic part of Durga Puja. Dom para of Calcutta execute to perfection the cane structures for making the canopy or pandal. In the far-away hamlets, womenfolk of Dom community weave kulo (cane plates) used during Durga Puja to make offerings to the Goddess. They also weave sturdy palm-leaf mattresses, which are immensely functional.

The artists drawing Chalchitra, Saaj, those making the idol of Durga, or the ones painting Lakshmi’s pata portrait are also directly involved with this creative spirit. Those making clay diyas, brass and copper utensils, hand fans, jal-chowki (a wooden low seater), decorative cut-out pieces of shola contribute to the stunning aesthetic impulse, surrounding this grand festival. This list would also include pata chitra painters, Durga Patas (traditional cloth-based scroll paintings), chalchittir (illustrations of folklore depicting vignettes of Durga’s origin and her divine achievements). For generations, the Sutradhar clan has been making the idol, especially the face.

The style followed by Sutradhar artisans to create the idol’s face is known as ‘Khash Bangla’ and the ones created by clay potters are referred to as ‘Dobhashi’ and ‘Chhobiyana.’ ‘Dobhashi’ is the creation of the mid-phase when the process of combining two styles was still on. Dobhashi deities have both conical features of the Sutradhar genre and a fleshy, heavyset face of clay potters. ‘Chhobiyana’ on the other hand, refer to real-life faces, resembling a film star, or a replica of a familiar face of a pretty woman. Perhaps a change in vocation, prompted a greater variety in the creation of Ma Durga’s face. But in whatever one creates, Durga Puja is all about inclusiveness.