Bengal’s most beloved graphic storyteller hits 96

For the home of a living legend, Narayan Debnath’s house on a narrow by-lane in Shibpur, Howrah is surprisingly nondescript. As we walk up to the gate and push it open, a bright-eyed stray dog greets us happily. An ordinary dog in an ordinary lane, leading to an ordinary middle class Bengali home with a courtyard at the centre and rooms all around it. There is absolutely nothing to suggest that this is the birthplace of such legendary characters of Bengali literature as Bantul the Great, Handa-Bhonda, Nonte-Fonte and Keltuda.

Purists may scoff at the description of Bengali comics as ‘literature’, as many are wont to do, but it is precisely this attitude that has robbed Debnath of his dues as one of Bengal’s foremost graphic storytellers, a genre that is yet to find its proper place in the Bengali literary canon. But more on this later.

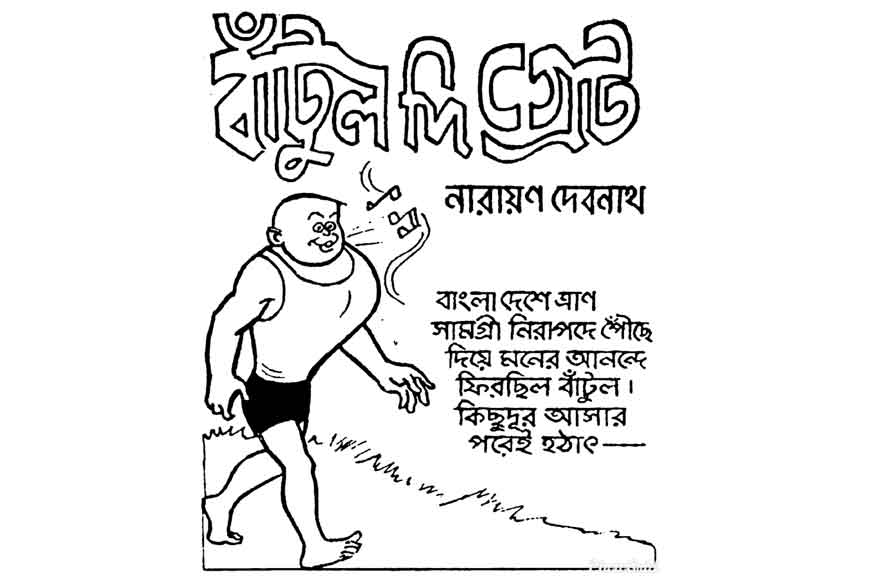

Bantul and the Bangladesh Liberation War

Bantul and the Bangladesh Liberation War

The man behind the immortal creations, who turns 96 today, has laid his brushes to rest after a career spanning over 50 years. He doesn’t talk much these days, and has been ailing for a while, as his daughter-in-law Archana Debnath gently reminds us. The child inside him emerges every once in a while when he meets an admirer or receives a compliment on his work, but age and disease have taken away much of his spirit. He is hard of hearing and takes his time to recognize even known faces. Unable to get up from bed, with no strength to speak, he merely shakes hands and smiles at us.

His kindness and generosity have always been well known, and in the past, fans were welcome to drop in at his home without prior notice. Even in these hard times, when he is unable to get out of bed, we are greeted by his daughter-in-law with utmost kindness and care. As she serves sweets and tea, dedicated Debnath fans like us cannot help but remember those delightful tales of Keltuda stealing sweets from the school boarding kitchen or Bantul gorging on a hundred sweets at a time. And that is appropriate, as Debnath has drawn most of his inspiration from real life. Even his pet dog was the inspiration behind Bantul’s pet dog Bhedo.

Bahadur Beral

Bahadur Beral

While many of Debnath’s characters have become nearly proverbial in Bengali popular culture and media, the man himself has led a humble life away from the limelight. A legend in the true sense of the term, his enormous contribution to literature and art has not received the acknowledgment it ought to have, owing in part to his reticent and kind nature. Even today, family members point out how his publishers have, over the years, paid him far less than what was due, or not paid him on time, forget about according him due respect as the only creator of his kind. In the past few years, he has had to face legal proceedings regarding copyright issues over his works, even as his dues have been withheld. More than one publishing house in Bengal has made a killing from the staggeringly high sales of his works, though he has rarely received his share of the profits.

Handa Bhonda

Handa Bhonda

Having begun afresh with a new publisher in recent times, it is a joy to realise that his works have lost none of their edge. Which is odd if you think about it, because his plots and characters are apparently relatable and mundane. The Handa-Bhonda series, first published in 1962, tells the story of two mischievous, adolescent Bengali boys. The success of this series caused Debnath to create Bantul the Great, first published in 1965, the homely superhero with inhuman strength and a humble Bengali heart. Not surprisingly, this humility is a characteristic of Debnath himself.

Debnath’s other celebrated series, Nonte-Fonte, was first published in 1969. While it began with a theme similar to Handa-Bhonda, the introduction of Keltuda and Superintendent Sir and the boarding school setting gave the series its unique charm.

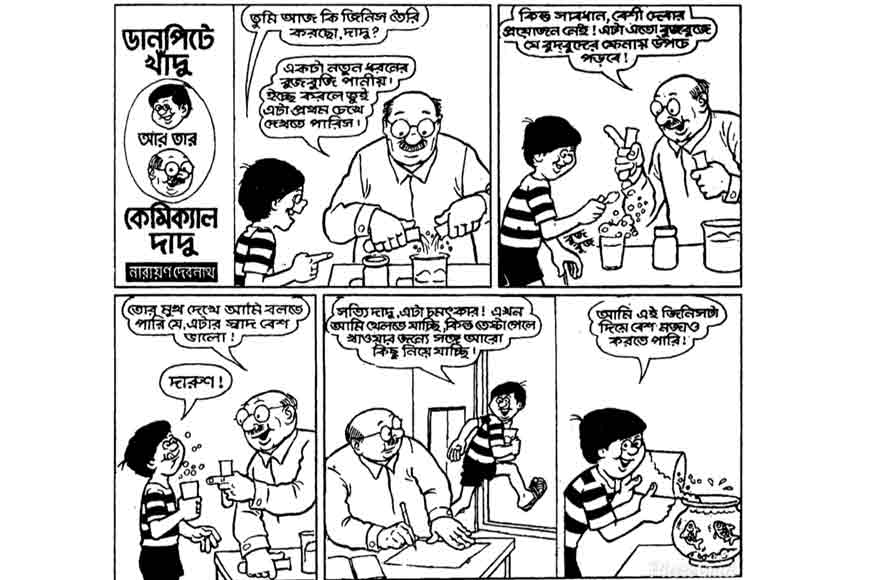

Danpite Khandu Aar Tar Chemical Dadu

Danpite Khandu Aar Tar Chemical Dadu

Though these are arguably his most popular works, Debnath’s range is truly immense. A personal favourite is Danpite Khandu Aar Tar Chemical Dadu (1983), which describes the adventures of a scientist grandfather and his mischievous grandson, much like the popular American sitcom Rick and Morty (2013). His works for children also include characters such as Bahadur Beral (1982), loosely inspired by Korky the Cat, Potolchand the Magician (1969), Shutki Aar Mutki (1964) and Petuk Master Botuklaal (1984). What’s more, Debnath has not confined his brush to children’s illustrations and comics, but stretched himself to create characters such as Goenda Kaushik Roy (1976), the protagonist of serious graphic detective novels.

To many so-called connoisseurs of literature, Debnath’s oeuvre may appear juvenile and ‘not serious enough’. However, careful examination paints a very different picture. Handa-Bhonda and Nonte-Fonte do not simply rely on slapstick, but focus on the witty use of terms and very relatable everyday situations, not unfamiliar to children who have grown up in Kolkata. Though some of his tales do share similar storylines, there are enough exceptions for us to acknowledge Debnath as a brilliant, socially relevant comic genius. For instance, a story in the Handa-Bhonda series has Bhonda dressing up as a ghost to scare off a real ghost, and the story ends with one of Debnath’s signature one-liners: “Bhootero tahole bhooter bhoy achhe, ki bolish Handa?” (So ghosts are afraid of ghosts too, what do you say, Handa?)

Also read : Sukumar Ray and the magical world of Pagla Dashu

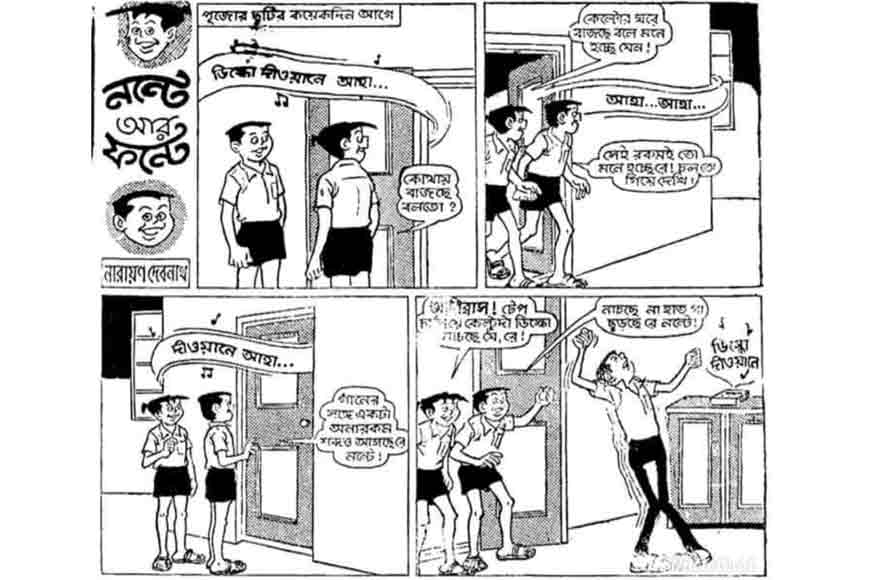

Having worked for over five decades with the same characters, Debnath has, over the years, made major and minor changes to keep up with the times, which has kept his popularity intact through generations. Though the characters have not aged, their ecosystems have become contemporary. For instance, while a Nonte-Fonte strip from the 1980s features Keltu dancing to the song ‘Disco Deewane’, a strip from the late 1990s features the same character grooving to ‘Chhaiya Chhaiya’. Again, Handa-Bhonda strips published after 2010 mention cameras and cellphones.

Disco Deewane

Disco Deewane

The use of certain terms and language has also changed based on the times. The earliest Nonte-Fonte or Handa-Bhonda comics were written in less colloquial Bengali, featuring words such as ‘kornakorshon’ (twisting of ears), while later strips feature a mix of English, Bengali and Hindi, as is common among modern Bengali speakers.

Debnath’s depiction of social classes through his use of language is also intriguing. Characters such as the thakur (cook at the boarding school), ojhas (local exorcists), fake godmen, thieves and goons, policemen and common people from rural Bengal make recurring appearances in all his works, and Debnath’s use of regional dialects to depict social backgrounds is significant, without any obvious discrimination or differenciation.

Keltuda and Saraswati Puja

Keltuda and Saraswati Puja

With the advent of gadgets such as the television and vacuum cleaner, Debnath skilfully made them part of Handa-Bhonda’s mischievous deeds, an upgrade from the days of bicycles and ‘danguli’ (gilli-danda). A late 1980s strip features problems involving a TV antenna, marking the omnipresence of TV sets in Bengali middle-class households. Debnath also incorporated objects such as roller skates, yoyos, toy guns, stamp albums and delicacies such as cheese, raspberries, strawberries, chocolate and bubblegum as and when they gained popularity among Bengali children as exotic items imported from the West.

Bantul and the Bangladesh Liberation War-2

Bantul and the Bangladesh Liberation War-2

And though the main aim of his works has been to entertain, Debnath has also painted a brilliant picture of contemporary socio-political events over the decades. In several Bantul stories from the late 1960s and early ’70s, he has placed Bantul in the backdrop of the Bangladesh Liberation War, where he serves as a saviour for beleaguered Muktijoddhas. Again, recurring characters Bhoja-Goja have been seen with revolvers and bombs, to be eventually overpowered by Bantul. Though all in good humour, the impact of the turbulent Naxalite era of the 1970s seems inescapable, though Debnath himself has never confirmed this.

In first world economies such as the USA, many parts of Europe, and even Japan with its booming manga industry, the existence of dedicated comic book stores selling expensive comic books, and highly feted comic artists are commonplace. In Bengal, none of these privileges have been offered to Debnath. For years he has remained, and still remains, the only significant artist in Bengal to have made a living solely from comics. While the production of comics in many other countries relied on a group of artists supervised by the main creator, Debnath has always been a one-man army, doing everything from the art to the dialogues singlehanded.

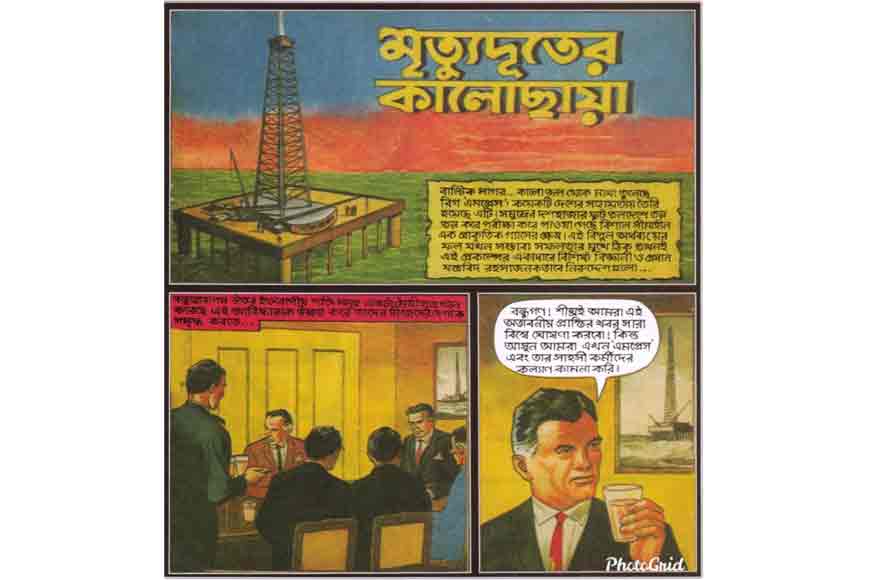

Goenda Koushik Roy

Goenda Koushik Roy

Today, he holds the record for the longest-running comic strip by an individual artist for Handa-Bhonda. This year, he has been awarded the Padma Shri. For every reader who has grown up reading Bantul and Nonte-Fonte, it is not the man alone who received the award - our childhoods did too. Yet, his first response to the news was, “They have finally chosen me?” Those simple words camouflage decades of hurt and sadness, of a legend who has probably not received the appreciation of his peers. Not until the 2013 Sahitya Akademi Award anyway.

As we enter his study, where his desk still stands with his inks and brushes intact, it feels empty. Much like the chair in front of the desk. The room is filled with gifts from fans and awards he has received over the years. But as someone who has grown up with his works and loved his characters since I was a child, this is not enough. It is necessary that Bengal introspects its treatment of some of its icons, and ponders over how its notoriously unprofessional and corrupt publishing industry has led to the creative death of more than one genius.

Potolchand the Magician

Potolchand the Magician

It is devastating that much of Debnath’s original artwork has been lost simply owing to criminal negligence on the part of publishers and editors. The coloured version of his comics now available in the market cannot compare to the black and white strips beloved of so many Bengali children. Bantul will remain the most loved Bengali superhero, without any of the ‘saviour complex’ common to DC or Marvel heroes, but the man behind Bantul is the true hero and will forever remain so.