From Pen to Frame: The Timeless Role of Letters in Ray’s Cinema - GetBengal Story

Letters have long disappeared from our everyday lives. Once, there were messages. Now, we just “text.” With a single tap, we can send words instantly, and with another tap, erase them forever. In such a time, it feels necessary to pause and think about the lost art of letter writing. Like everything else, our ways of communicating have also “modernized.” We don't have to rely on pen or paper anymore to share our work, our feelings, or sometimes even our innermost thoughts. Images, emoji, and digital expressions have replaced our handwritten emotions. But the comfort, the longing, and the closeness of writing and reading letters felt seem to no longer exist - when people would sometimes wait days, even months, for letters to arrive. The person writing the letter had to choose every word carefully, knowing it was the only way to express their heart. That waiting, that anticipation, that silent emotional storm—letters carried all of it.

And this brings us to the use of letters in Bengali cinema—more specifically, in the films of Satyajit Ray. It’s well known that after Mrinal Sen’s Akash Kusum released, Satyajit Ray expressed his strong objections through a series of letters. Those letters and their replies soon turned into an exchange filled with bitterness. What’s striking is this: today we quarrel and argue so easily, almost thoughtlessly. But in those times, one had to frame every thought carefully, shape every word, and then put it down with clarity. The process itself left little room for forgetfulness, even for the language we used. And yet, we mustn’t forget—Satyajit was, at heart, a modern Bengali artist. His films, frame after frame, testify to that. Which is why looking back at how he used letters in his cinema feels especially meaningful.

Indian cinema, across industries, has often fallen into the trap of imitating a single cinematic device until it becomes formulaic. The portrayal of letters on screen is no exception. The typical scene: the camera peers over the shoulder of the actor, the letter fills the frame under a strong spotlight, and soon we hear the sender’s voice reading it aloud, or perhaps see their face dissolve onto the screen. But Ray, with his modern sensibility, broke this monotony.

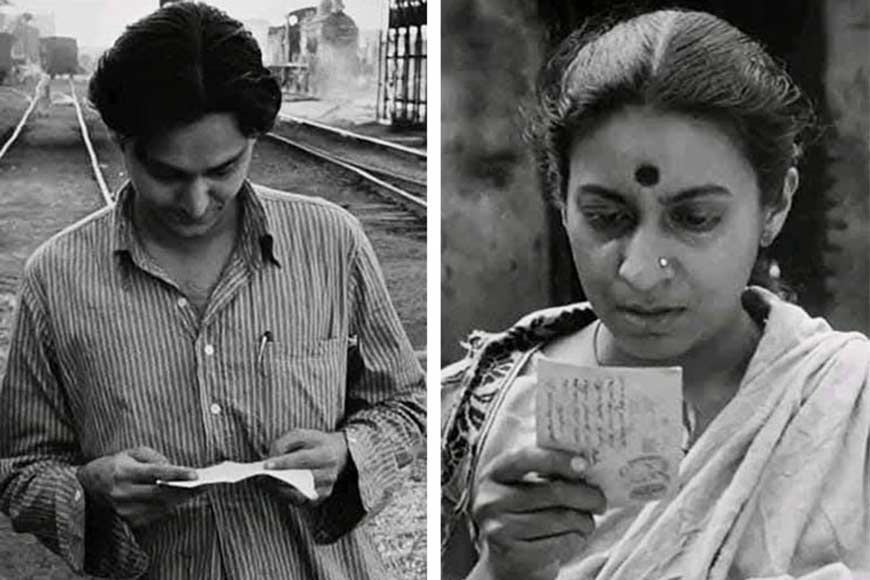

Take Pather Panchali. When Sarbajaya finally receives a letter from Harihar after a long gap, we do hear Harihar’s voice reading it, but Ray’s camera lingers on Sarbajaya’s face. Her expression changes gradually—from concern and exhaustion with struggle, to relief and happiness hearing the good news. In Aparajito, when Apu is writing a letter, it seems as if we are reading it with him. Like the secret joy of reading a novel, Ray intended for the viewers to be involved in this moment.

One particular scene stands out—Apu receives a letter from his mother. His employer at the press, curious at his eagerness to read, asks whether the letter carries bad news. Even this act—the physical presence of a handwritten letter—was something Ray began to give weight to.

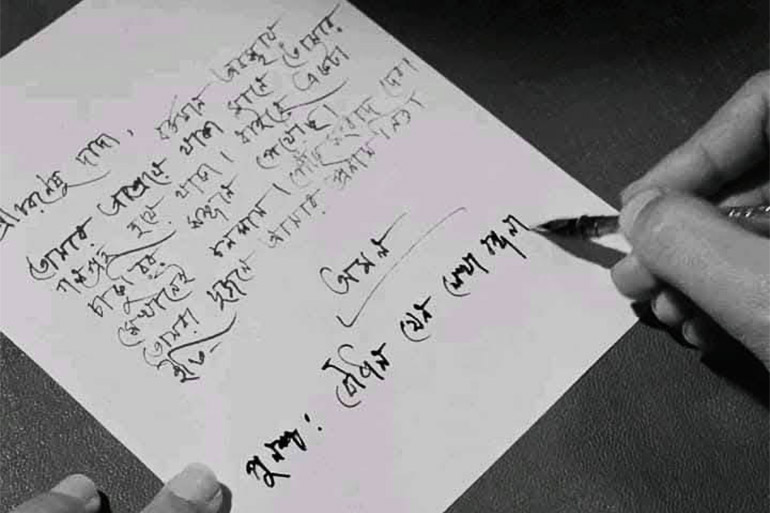

And then there’s Charulata. Soumitra Chatterjee, as Amal, spends scene after scene with pen and paper, writing poems and stories. Soumitra himself once said that Ray had made him practice handwriting so meticulously that it even shaped his natural writing style later. Those scenes—hand on paper, words flowing line by line—were Ray’s way of pulling the audience into the act of creation, making them silent participants.

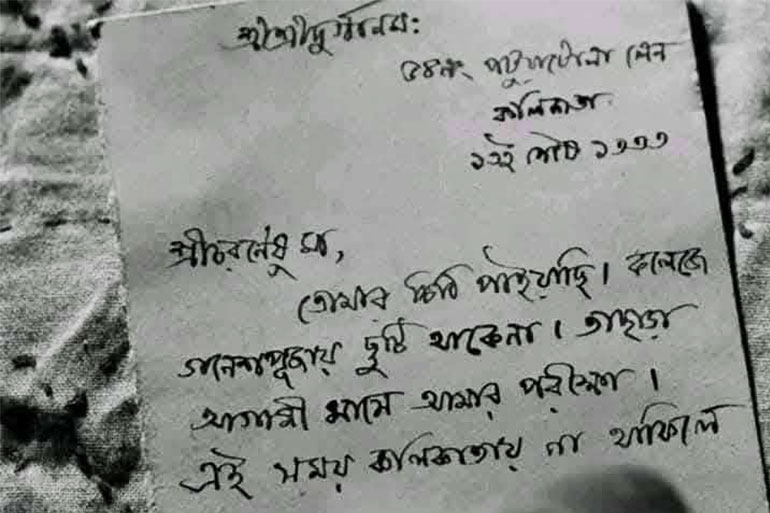

Letters appear again in Aparajito and even more prominently in Apur Sansar. The film itself opens with a letter—not read aloud, not dramatized, but shown in English handwriting, barely legible, hinting at opportunities in Apu’s career after college. Those who study Ray closely know—that handwriting was Ray’s own. Later, in a famous sequence, Apu reads Aparna’s letter while walking along the railway tracks near Sealdah. Aparna's voice is heard in the background, but Ray keeps the focus on Apu's face, his emotions. The moment of tenderness quickly collapses when Aparna's brother comes with the shocking news—the death of Aparna in childbirth.

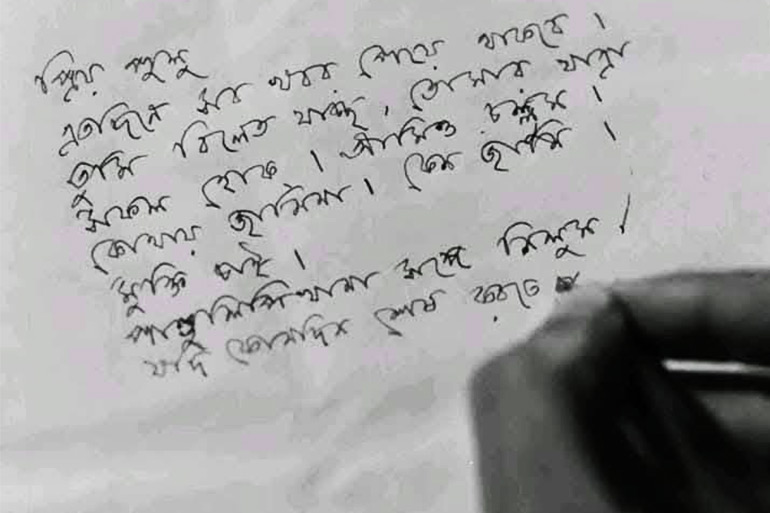

And then the final letter—Apu writing to his friend Pulu about his disappearance. “I am taking the manuscript with me. Once it’s finished, I’ll send it to you.” The phrasing itself—so intimate, so poetic: “May your journey abroad be successful. I too set out on mine.” Here lies the subtle shift Ray brought. Once, formal, ornate language dominated letter writing. But as his films progressed, Ray showed us a modernizing world where even letters reflected more personal, conversational tones.

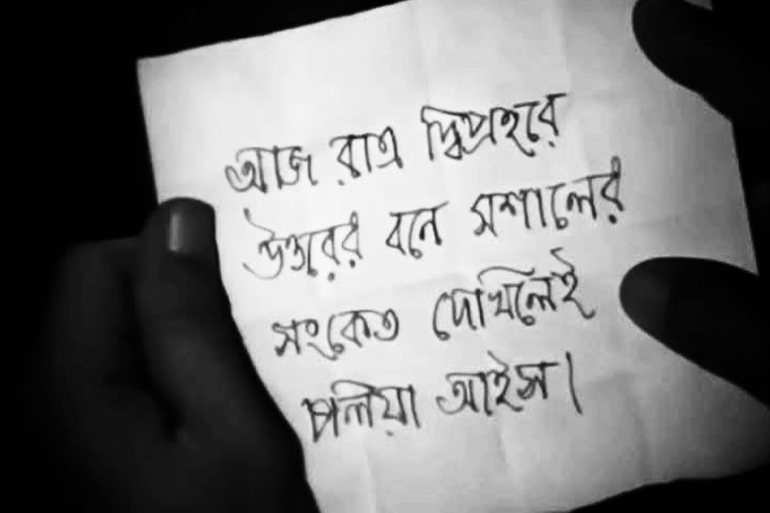

Another unforgettable letter comes in Chiriakhana. Midnight in Golap Colony. Panu Gopal sits down to write to Byomkesh Bakshi, starting with “Shreecharaneshu.” His handwriting is shaky, faltering, sentences uncertain. Just as he writes, the killer approaches. In one chilling cut, the pen breaks, Panu collapses forward, and the scene plunges into darkness. Ray’s attention to detail is striking—Panu’s broken sentences and hesitant words reveal his struggles to express himself, and in that very vulnerability, Ray plants the seed of tragedy.

And then there is Agantuk. The film begins with a letter—anonymous. We are not given any details about the author, including their identity, origin, or their intent. The letter is composed in formal Bengali, which certainly conjures for us the image of an educated older gentleman. By establishing this frame, Ray allows the viewer to share the couple’s doubt and uncertainty so that when the truth arrives, it rings true to the viewer’s own awakening.

Even in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, letters play a role. The news of war arrives in a written decree—its words symbolic, almost pictorial, so that even a child could understand it: elephants, horses, swords, shields. Later, we see the Prime Minister of Shundi hand the king a letter: “There is still time. Shall we send an envoy?” Even the shape of the letters—slightly smudged ink, blunt strokes of ‘ka’—is captured in detail.

This was Ray’s gift. Where others used letters as props, he transformed them into living expressions—vehicles of emotion, anticipation, and meaning. His attention to handwriting, phrasing, and the reactions of those reading made these moments unique, setting his films apart from the formulaic patterns of his contemporaries.

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here.