How a transport strike changed Calcutta’s traffic for good

It was French journalist and novelist Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr who in 1849 first coined the saying, “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” (the more things change, the more they remain the same). He could easily have been talking about what is said to be India’s first ‘transport strike’, which was called, where else but in Calcutta? What’s more, the man who allegedly led the strike even held a public meeting at Dharmatala!

The year was 1827, nearly two centuries ago in other words. Of course, the Calcutta of those days was nothing remotely like the Kolkata of today, but the pace of urbanisation had picked up after more than a century of East India Company rule, and the traffic system had become complicated enough for the administration to issue a new set of rules and guidelines for it.

Therein lay the problem. The new rules were meant primarily for the city’s many palanquin or palki bearers, who were furious at this attempt to regulate their operations, and promptly went on strike. Some sources mention one Panchu Sur, who reportedly led the strike and staged a rally at Dharmatala, though the name probably finds no mention in any known official document. Nonetheless, whether it was Panchu Sur or someone else, it is well documented that towards the end of May 1827, hundreds of palki bearers went off the streets of Calcutta for almost a month.

What were they protesting against? Prompted by a flood of complaints about the apparently extortionate rates charged by the bearers, the administration declared that palkis could not charge in excess of three annas (one anna was roughly equivalent to 6.25 paisa, impossible to compute in terms of the current rupee) per mile. Also, every palki bearer would have to carry a numbered metal token, their palkis would bear numbers too, and each bearer would have to get himself registered with the police. Incensed by these directives, the palki bearers declared that they were shutting shop.

Also read : Tracing the 'Bangali gaddis' of Burra Bazar

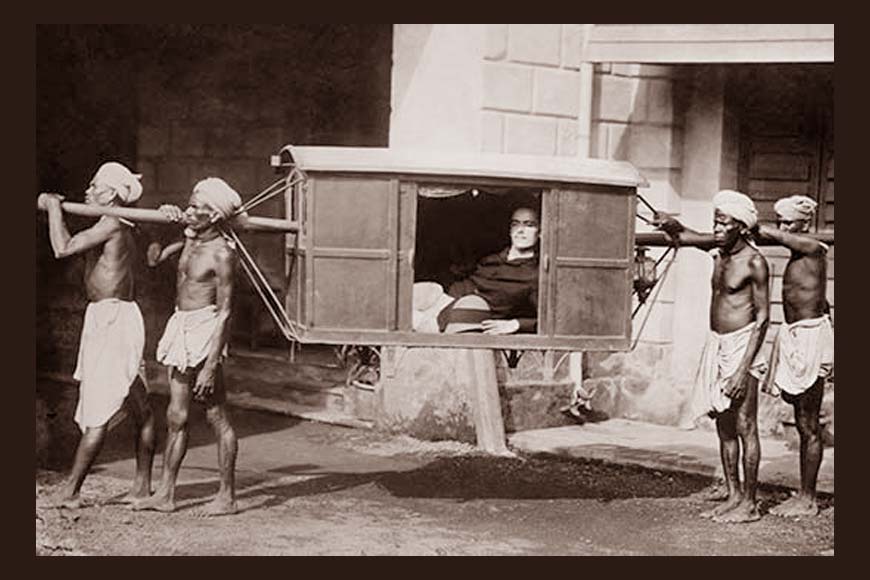

In today’s terms, the closest example would probably be a bus strike, and we all know how very hard that is on the average commuter. Calcutta in 1827 underwent a similar turmoil as the public transport system all but broke down in the absence of palkis. Cutting across class barriers, the palki was the most convenient mode of transport for citizens, with the British ruling class and even many upper-class Indians flaunting their deluxe human-borne sedans. In his 1895 booklet ‘Old Calcutta, Its Places and People a Hundred Years Ago’, the Rev. W.H. Hart wrote, “In 1780 we are informed that a Captain in garrison required about thirty servants. These included a pipe bearer (the Hukabadar), eight bearers for the palankeen, and a linkboy.”

At the end of their rally at Dharmatala, thousands of agitating ‘palankeen’ bearers reportedly walked to Lalbazar in procession, intending to stage a demonstration in front of the city’s administrative headquarters. With the city almost at a standstill, and no acceptable solution in sight, a certain Mr Brownlow entered the picture. Unfortunately, history tells us nothing much about this admirable gentleman, other than his remarkable inventive abilities which helped at least partially resolve the ‘palki problem’.

Brownlow removed the rods from a palanquin and attached wheels to it, thus creating a box-carriage to be drawn by horses, giving birth to what Bengalis called the ‘chhyakra gari’, and also laying the foundation of Kolkata’s traffic policing system. In his honour, the British named his invention the Brownberry.

Thus it was that a transport strike forever changed the face of Kolkata traffic. Of course, the palki did not go out of fashion overnight. In fact, it remained in use for more than another century, but it was no longer the city’s major mode of transport. Both the average citizen and the sahib now had other options.