In the heart of Kolkata resides a gentle, often ignored Buddhist story - GetBengal story

There is a saying: “Atithi Devo Bhava”—the guest is akin to God. The Taittiriya Upanishad speaks of this philosophy, and we witness its finest expression in this metropolis. One wonders if anywhere else, apart from Kolkata, exists such an organised coexistence. Kolkata—the city of Koli. Kolkata—the city shaped by Time. From a humble cluster of three villages to its present expanse, the journey has been long. Over the ages, many chapters have merged into its flowing history. Whether language, religion, caste, community, or new waves of people—this city has welcomed all with open arms. Like a simple peasant laying out a mat for a guest, Kolkata has offered warmth and hospitality to everyone. Yet, in the conventional narrative, some chapters remain neglected. Today, we explore one such largely overlooked story—the Buddhist culture of Kolkata.

It was the era of the East India Company. Kolkata, the capital, was bustling with newly arrived communities. As the direction of trade in the subcontinent shifted, various peoples began to gather here. Alongside Western arrivals like the British, French, Italians, Portuguese, Greeks, Armenians, and Jews, came the Chinese, Tibetans, Sinhalese, and Japanese. Through this influx from the East, the city once again came into contact with Buddhism. Yet Buddhism was nothing new to Bengal. Connections existed since the time of Gautama Buddha himself. Under Emperor Ashoka and later the Pala dynasty, Buddhism flourished extensively. During the reign of the Palas, Buddhist influence on society, literature, art, and philosophy was profound. Charyapada, the oldest known form of Bengali literature, is rooted in the Sahajiya practice. The earliest illustrated manuscript, Manjushri Mulakalpa, contains rituals from Vajrayana Buddhism. From sites like Somapura, Jagaddala, and Raktamrittika, or from personalities like Atisa Dipankara, the deep imprint of Buddhism in Bengal becomes evident. But that is another discussion—let us return to Kolkata’s story of Buddhist culture.

Old Kolkata was multidimensional. To this melting pot of blended cultures, Buddhist heritage added its own unique layer. Modern Buddhist culture in Kolkata evolved largely through various Asian communities and through the revival of Buddhism in Bengal. In this, Buddhist places of worship played an important role. Even today, several monasteries and temples stand in the city—such as the Mahabodhi Society, Bauddha Dharmankur Sabha, Nipponzan Myohoji, Karma Gon Buddhist Monastery, and others. Amidst the city’s endless rush, these spaces continue to hold their quiet, fading presence.

It seems to take you to another time and place. Walk up the stairs to the second floor, and you are in "Sikkim!" The walls are ablaze with colourful frescoes of the life of the Buddha, Jataka tales, and objects from around the world mingling with what seems like a mystical smell. This is the Mahabodhi Society on Bankim Chatterjee Street next to College Square, founded in 1920 by Anagarika Dharmapala, although the society's first office was started in 1892 at 20/1 Gangadhar Babu Lane in Bowbazar. After moving to Creek Row and moved again to their present location. Dharmapala himself, at a young age of 26, travelled extensively, to places such as Gaya, Sarnath, Kushinagar and even the far west, to propagate Buddhism in India. In 1893 he represented Buddhism at the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago. Many notable figures of the time supported the society. Even today, people come here regularly. Special events are conducted on the day of Buddha Purnima. The monastery is open for all to visit from the hours of 6AM to 8PM, for daily prayer and meditation.

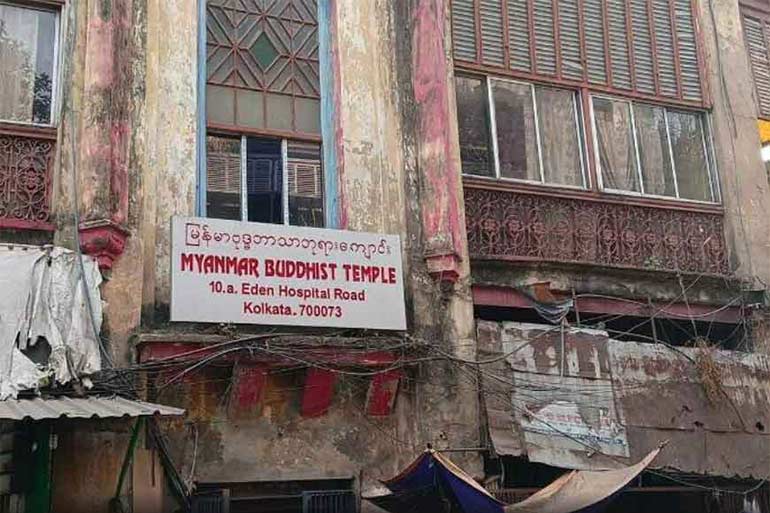

Not far from here are two more temples. Walk down Surya Sen Street towards Central Avenue. Turn left upon reaching the main road. The tight clusters of buildings on Eden Hospital Road reveal little from outside—truly, “Don’t judge a book by its cover!” You must look for a mailbox labelled “Myanmar Buddhist Temple, 10A Eden Hospital Road”. Now, of course, there is a signboard. The lone Burmese temple of Kolkata was founded in 1928 by U Sein Min. Back then, it was a famed resthouse. The first and second floors served as guest rooms, while the temple sits on the third. The small, neat prayer hall is filled with flowers. A golden Buddha sits serenely, eyes half-closed. Many Burmese immigrants once came to India—some as refugees, others for livelihood. They settled in Delhi, Mizoram, Assam, and in West Bengal at Kamarhati and Barasat. In Kolkata, they lived around Poddar Court and Tiretta Bazaar.

From the Burmese temple, walk towards Bow Barracks. Beside this Christmas-lit lane stands the Bauddha Dharmankur Sabha, founded in 1892 by Kripasaran Mahasthavir, known as “The Maker of Modern Buddhist Bengal.” The institution hosts conferences, rituals, award ceremonies, and even runs a clinic for all. It is also an important centre for Pali studies and Buddhist scholarship.

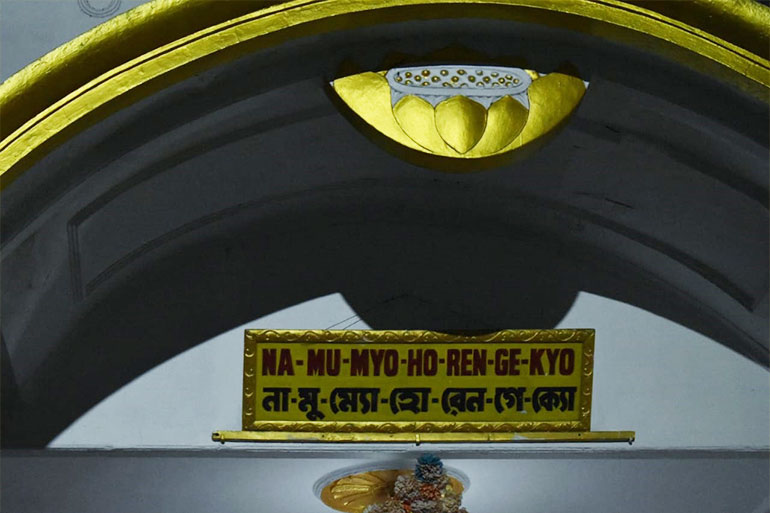

Let us head to the south now. Nipponzan Myohoji, the only Japanese temple in the city, is located on Lake Road, and was established in 1935 by Nichidatsu Fujii, who had been a disciple of the 13th-century monk Nichiren. Nichiren had once dreamed that his teachings would be spread throughout India. Nearly 650 years later, in 1931, Fujii arrived in Kolkata to complete his master’s dream. He faced financial difficulties but was helped by a number of supporters, including a strong supporter, industrialist Jugal Kishore Birla who offered land in Dhakuria for the temple. The building design has a very Japanese feel. The white shrine, resembling the Sanchi Stupa, bears plaques carrying messages of peace. Inside rests a serene white Buddha idol. Every evening, rituals are performed to the beat of the taiko drum, and seven sacred sounds are chanted—“Na-Mu-Myo-Ho-Ren-Ge-Kyo”: I devote myself to the Lotus Sutra. As dusk falls, people seeking solace arrive—men, women, elders, youth. A young man in his thirties tells us:

— How long have you been coming here?

— For a few years.

— Do you come regularly?

— Not every day, but often.

— Why do you come?

— I find peace.

Many Kolkatans fondly call Nipponzan the Peace Pagoda.

If time permits, visit Ballygunge next. Around Padmapukur and Chakraberia stands the Karma Gon Buddhist Monastery, established in the 1930s by monk Akka Dorji from Darjeeling. The monastery follows the Tibetan Karma Kagyu tradition.

Let us wander now into the newer Chinatown—Tangra. The Chinese began arriving in Kolkata in the 18th century. Initially they settled near Tiretta Bazaar, and by the 1920s created a new settlement in Tangra. Famous primarily for food, this area also houses a unique monastery—the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist Monastery, founded in 1998 by the Taiwan-based Buddha Light International on 8 New Tangra Road. Lion statues guard the entrance. Beyond an open courtyard lies the main hall where everyone is welcome. Alongside daily worship, it houses a library and calligraphy classes. The monastery also runs a vegetarian eatery from 11 AM to 6 PM with no fixed menu. Many visit for its unique teas. There are other monasteries across Newtown and the Bypass too—Garia Buddha Mandir, Dharmachakra Vihar, and Bedarshan Learning Centre. Buddhist culture in Kolkata extends far beyond temples—it blends into food, fashion, and lifestyle. Tibetan and Chinese localities charm visitors with the aroma of momos and thukpa wafting through the lanes. In fact, Buddhists have revolutionised the city’s food culture.

Today, momos are found everywhere—every few steps a stall appears. They now compete head-on with Kolkata’s fuchka, biryani, and chops. Some serve four pieces, some five, some seven or eight. Many mistakenly think momos are Chinese; in truth, they originated in Tibet. In the 17th century, Newari traders invented this meat-filled delicacy. As they travelled, the dish spread—first to Nepal, then Darjeeling, Gangtok, Kalimpong, and eventually the hills. Momos arrived in Kolkata only in the 1980s. A Tibetan couple opened a small shop near Elgin Road crossing—“Tibetan Delight”. Beyond a narrow alley lies a magical, Arabian-Nights-like world. “We were the first to bring momos to Kolkata,” says the current owner. “My father-in-law started the business. He was a kind man. Momos cost only 25 paise then, and he gave discounts to students.” Within a year, several other shops emerged—Orchid, Hamro Momo, Blue Poppy, Sikkim House. Each excelled in something—noodles, thukpa, chopsuey. From North Kolkata’s Gunjhan to South Kolkata’s Denzong, the city remains lively with momo culture.

Buddhists have influenced Kolkata’s clothing too. Winter is coming. Each November, Wellington street lines up with stalls run by Bhutanese and Tibetan vendors, selling soft woollen sweaters, blankets, ear-caps, mufflers, and jackets. People still flock here to buy winter wear. And for lovers of the mountains, there is always Chamba Lama for jewellery and souvenirs.

There are countless such stories in this city. Through its evolving years, people of all faiths and backgrounds have contributed. The spirit of pluralism runs through Kolkata’s veins. We easily embrace all that is good—whether it be Eid’s crescent moon, Parasnath Jain rituals, Santa Claus, or the Laughing Buddha. These have strengthened and enriched Bengal for generations. “We shape the world through our thoughts,” said the Buddha. May this message hold true. May Bengalis continue to live in harmony. May this beloved city continue to thrive.

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here.