Unveiling kolkata: the forgotten synagogues and stories of timeless harmony - GetBengal Story

We were walking north along Netaji Subhas Road, west of Lal Dighi, passing on the left the GPO, the Reserve Bank, and the Eastern Railway headquarters, and on the right, Writers’ and Lions’ Range behind us. By “we,” I mean myself, my American friend Dr. Steven Emet, and his Japanese wife Yuki. We were exploring a part of our city whose existence I had never even known!

- “When you think of Jews, who comes to mind first? Shylock or Einstein?”

Yuki asked me, a mischievous smile in her eyes.

- “No one, because I don’t know either of them.”

- “Good! So, who do you know?”

- “Steve Emet!”

We all laughed together. About three months earlier, Steve had written to me from San Diego, California, asking whether it would be right to visit Kolkata’s old synagogues while I was there for a lecture.

Steve, I mean Professor Steven D. Emet, is a professor in the dermatology department at the University of California. I was stunned. A synagogue? What is that? Are there any in Kolkata? Where? I remembered Shankha Ghosh’s immortal line: “There is another Kolkata within this Kolkata.” But I didn’t know this Kolkata. How could I take a guest there?

First, I went to Nahum’s shop in New Market to inquire. They told me that one needs permission from the Affairs Secretary of the Jewish community, M.H. Cohen, to enter the synagogues. I had to email for permission. I did, and got a reply from Joe Cohen.

Ahead, at the India Exchange crossing, the soft winter sun fell on the Axis Bank. The street split into two. The right side was Dr. Rajendra Prasad Sarani, leading to Canning Street. The side street was Indrakumar Karni Street, and next to it was Synagogue Street.

Steve is a man of wonder. There is no country in the world where he hasn’t set foot. Generous, anti-war, deeply knowledgeable about Jews, yet without any communal bias. Before going and after reading a bit, I understood this much: Kolkata’s three famous synagogues are in this area — Neveh Shalom (1831), Beth-El (1856), and Magen David (1885). Steve also mentioned that there had been two more: Magen Aboth (1897) and Shaar Rason (1933). The Magen Aboth synagogue on Blackburn Lane no longer exists; it was demolished. Shaar Rason is also closed.

Honestly, aside from the Holocaust in WWII and the later inhuman treatment of Jews in Arab countries, I didn’t know much about Jewish history. Shalom Aaron Obadiah Cohen, a Jewish Baghdadi merchant, came to India in 1791 from Baghdad, Hillah, and Basra. First to Surat in Gujarat, he succeeded in business, then moved through Bombay, Cochin, Madras, and Hugli, finally settling in Kolkata. The first documented permanent Jewish resident of Kolkata was Shalom Aaron Obadiah Cohen.

Steve told me that even a decade before Cohen arrived, a Jewish trader named Lyon Prager had come to Kolkata in 1786. However, Cohen was the founder of a community, and through him, the permanent settlement of Jews in Kolkata began. In 1831, Cohen built Neveh Shalom Synagogue in memory of his father Shalom Ha-Cohen. This was Kolkata’s first Jewish place of worship.

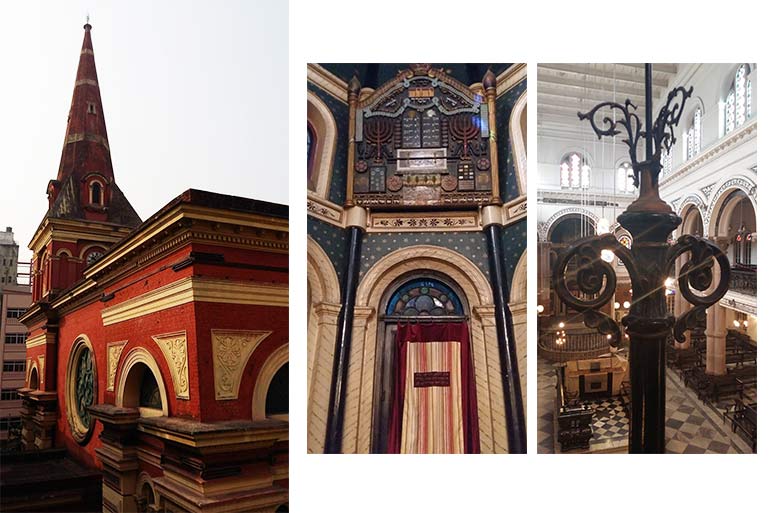

Originally a residential space, it became a prayer hall later. It was located at the junction of Canning Street and Brabourne Road, where today stands Magen David. Many Baghdadi Jews at the time were living in the area. Beth-El Synagogue was built here in 1856. In 1883 with the demolition of the old Neveh Shalom, Magen David Synagogue was built, which was designed by Elias David Ezra in memory of his father David Joseph Ezra. This is a jewel of Kolkata’s Jewish heritage featuring Italian Renaissance style architecture, a tall tower of 142 feet, and a special clock imported from London.

Inside, the visitor is greeted by colourful stained-glass windows, black and white checkered marble floors, ornate columns from Paris, sparkling chandeliers, and more than a few old photographs and documents. This synagogue is a living tribute to the cultural and commercial inputs of Kolkata’s Baghdadi Jewish community. In 1911, a second and larger Neveh Shalom Synagogue was built at 9 Jackson Lane beside Magen David, and completed the following year. We were spending the morning in parts of the city that I had never known existed!

Steve had given me a hint earlier, but seeing it firsthand left me astonished: all the staff of these three synagogues are actually Muslim! Generation after generation, they have preserved this heritage. Not only is this astonishing, it is truly heartwarming. Alwar Khan, Rabul, Ibrahim — and the eldest, Mohammad Khalil, who has worked here for six decades. Also Siraj Khan, Asim — each one an integral part of these historic establishments. Religious divisions are completely irrelevant here. Through generations, Anwar Khan, Masud Hossain, Mohammad Khalil, Siraj Khan, Asim, and Alwar Khan have maintained Kolkata’s oldest Jewish synagogues.

They do not follow the Arab-Israel war news either. I learned that none of these three synagogues hold regular Saturday services anymore, as the required quorum of ten members cannot be met. Siraj took us to the nearby Armenian Church, and I realized how meaningless and artificial religious divides can be. These synagogues are not merely religious spaces; they are unique symbols of Kolkata’s pluralistic cultural past.

Here, the true diversity of Kolkata is felt. The destructive power of today’s senseless conflicts seems lost in this city. Multiple languages, cultures, and religions have merged into its streets. How could this not be amazing? The Armenian community is more than three centuries old. Some of the tombs were there long before the founding of Kolkata, dating back to the early part of the 17th century.

Before visiting the shuls, I had spoken to Mrs. Cohen on the phone several times and learned about the family's history of Mordecai Haim Cohen. He had the kind of story that felt like a fairy tale - his family came from Isfahan, Iran, to Dhaka with stops in what was then Rajshahi in the mid-nineteenth century. While his family was from Iran, his mother was a kolohta', a Jew from Kolkata, and he was born in Bowbazar. He attended school and college in Rajshahi, identifying himself as a Barendra Jew. He was the first television announcer and newsreader in Dhaka during the Pakistan TV era. After independence, he continued in Bangladesh. Mrs. Cohen said that when he came on leave, he would feel very happy in Kolkata, loving Bengali language and music.

I later read in a leading newspaper by Riju Basu: “I could not explain to you with my eyes even today, perhaps this is not the last time we will meet!” Manna Dey sang aloud, narrating the life of Mordecai Haim Cohen, one of Kolkata’s last Jews. At 74, his body weakened by terminal prostate cancer, he still lived surrounded by music and books by Sarat Chandra. Even during radiation treatments, he would captivate doctors with his singing. Surrounded by Manna, Hemanta, Manbendra, Shyamal, Kishore, Dhananjay… he would recall Rajshahi: “Do you know it’s called Barendra? That’s where my school and youth were!” At that time, Bangladesh was politically turbulent, yet his connection to Bengali culture remained strong.

Finally, we met Mrs. Cohen that miraculous morning at her home at the Jewish Girls’ School on Park Street. Another surprise: the school had a vast green field, but none of the students were Jewish — mostly Muslim and Anglo-Indian. Calm, graceful Mrs. Cohen exuded dignity. Many conversations about Mordecai followed. We heard that he had improved slightly and might be given leave. His life, steeped in Bengali music and culture, radiated joy despite illness. We were laughing together when a call came. Joe Cohen spoke quietly and then told his assistant to serve us tea and coffee. Then, in his normal voice, he looked at us fully and said:

- “I am sorry, I’ll have to leave. Mordecai Cohen is no more. His leave has ended.”

The day was December 16, 2015. In 1798, Shalom Aaron Obadiah Cohen, the first Jewish businessman, arrived in the city from Baghdad. 217 years later, the luminous, wonderful Mordecai Haim Cohen — a symbol of Kolkata’s pluralistic religious harmony and cultural heritage — passed away.

A Barendra Jew. Whom I had never met.

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here.