Indigenous rice of Bengal: Procedure of cultivation and preservation – GetBengal story

In the fertile, silt-rich Sundarbans, during the Kharif season, farmers used to harvest good yields of various indigenous rice varieties without using any chemical fertilizers or pesticides. Different local types of rice that could withstand floods and salt were grown and maintained for generations on high, medium, and low-lying lands. But where would corporations make money if farmers continued to be so independent?

So, in the 1980s, the "company’s" chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and seeds entered the market. It came as a package, if you bought those hybrid seeds, you also had to buy large amounts of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and seeds; you needed plenty of groundwater, which meant pumps, pipes, and other equipment would also sell in huge numbers. In this way, the farmlands of the Sundarbans gradually became degraded, and within just a few decades, most of the indigenous rice varieties nearly disappeared.

Although natural causes of pollution exist, the excessive use of fertilizers and pesticides has led to the degradation of soil health, causing a decline in rice yields. At the same time, farming costs have risen so much that farmers, burdened with debt, are pushed to the brink of survival, while the price of rice remains lower than its fair value. In such a situation, many are giving up farming altogether. The present generation in many families has become disinterested in agriculture.

In fact, this is precisely what the state has wanted. Once farmers willingly abandon their land, they can be made to enter into various kinds of contract farming. Because of the collapse of agriculture in the Sundarbans, large numbers of people are migrating elsewhere in search of work. This phenomenon can be called “ecosystem refugees” — that is, people being forced to migrate because the ecosystem has been deliberately destroyed.

But after the Yaas cyclone and the floods, day and night I kept hearing people talk about different indigenous varieties of rice. In reminiscing, they would describe the height of the paddy plants, the colour of the grains, the shade of the rice, and the taste of the cooked rice, puffed rice, or popped rice. They also said that in such post-flood conditions, only those traditional rice varieties could truly protect the farmer. Their yields might be lower, but “they will never betray the farmer.”

The context of this discussion is Kamdevnagar village in the Durbachati Gram Panchayat, on the banks of the Saptamukhi at Selemari, in the southern Sundarbans. The soil here is clay rich, and a large part of the village is low-lying. Because both saline and freshwater from floods often remain trapped in these fields, agriculture suffers in many ways.

Environmental pollution, both natural and man-made, has greatly increased. Sea temperatures have risen, and as a result, the Sundarbans have seen a rise in the intensity of cyclones and floods. On top of that, the rise in sea level in the Sundarbans has been higher than in many other parts of the world. After Aila, there was a gap of a few years, but then devastating disasters struck one after another like Fani, Bulbul, Amphan, Yaas etc.

Villages such as Kamdevnagar and Harekrishnapur are among countless others that are quite low-lying, with relatively little high ground. Because there has been no proper planning for village settlements, many places lack adequate drainage systems. As a result, after saline water entered, it remained stagnant in these villages , for fifteen days in some places, a month in others, and even up to two months in certain areas.

In these rapidly changing climatic conditions, the high-yielding varieties of rice that farmers had been cultivating are no longer able to survive. Somehow they manage during the Aman season, but the Boro season no longer gives good results. Yields are declining. Soil health is deteriorating steadily. Farmers’ incomes are falling.

Why?

Let me explain: high-yielding varieties are also high-responsive varieties. That means, in order to grow these seeds, excessive amounts of water, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides are required. As a result, beneficial organisms in the soil, such as microbes and earth worms , are destroyed. A huge amount of groundwater is consumed for irrigation. Predatory insects, which used to eat herbivorous pests, die off, and so the infestations of rice-eating pests keep increasing. Earlier, farmers generally knew of three types of pests; now that number has risen to around twenty-five or twenty-six! Why? Because we have destroyed the natural ecosystem of the fields. We have broken the food chain.

In the Ganges delta of South Bengal, the staple food of people is rice. Rice gives them the energy to work from dawn to dusk. In the morning, panta (fermented rice), at noon rice, and again rice at night. But if things go on like this, even rice itself will become scarce. [As for ration rice? That has many problems, which must be discussed elsewhere.] Farmers may also rightly ask: “Why should I eat that polished ration rice when I still have my land?”

Anyway, to cope with the unstable situation caused by the floods of saline and freshwater, the variety Nonashree rice was introduced. But in Kamdevnagar, after cyclone Yaas, many farmers did not accept it. Those who did found that Nonashree performed so poorly in their fields that they were forced to lodge complaints with the agriculture department (though they knew it would be of no use). Many farmers refused to take that rice at all.

From memories of a few decades past, farmers now began to realize that in this tragic situation, what was truly needed were the indigenous rice varieties of the Sundarbans.

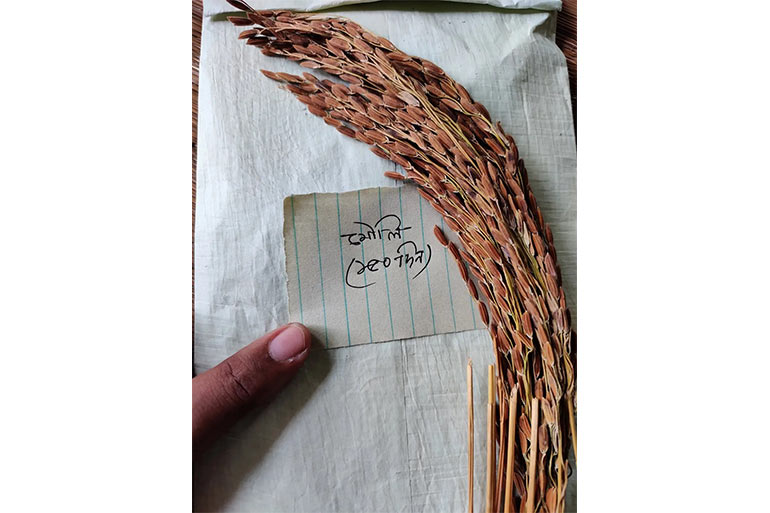

Bhurishal, Nangolmura, Talmugur!

But many of those varieties are no longer around. Among indigenous rice, what farmers mostly have left in their hands is Doodher Sor and Morichshal (excellent for making puffed rice and popped rice). A few others still exist, such as ChamarMoni, Sitashal, Rupshal, and Kaminibhog, but their numbers are limited. Many farmers no longer have access to them at all.

Doodher Sor still survives because it gives good yields, produces fine slender grains, and is very tasty to eat. Taken altogether, these qualities have helped it endure. Another special characteristic of Doodher Sor is its “elongation ratio” — that is, the way the rice grains expand when cooked. In this respect, Doodher Sor remains one of the most important varieties in the country.

But many of those varieties are no longer in existence. Among indigenous rice, what farmers mainly have left are Doodher Sor and Morichshal (the latter makes excellent puffed and popped rice). A few others, like Chamarmoni, Sitashal, Rupshal, and Kaminibhog, still exist, but only in limited numbers. Many farmers no longer have them at all.

But with so little rice diversity left, and only the high-yielding varieties to rely on, the Boro season can no longer be managed. Someone may well ask: Why grow rice in the Boro season at all? It depletes the groundwater.

And here lies the real value of indigenous rice! If a wide range of traditional varieties were still in hand, farmers could choose from rice strains that mature in anywhere between 60 to 200 days. One could calculate in advance exactly how much water would be needed per bigha or per kilogram of rice. Even today, there are farmers who cultivate indigenous rice during the Boro season using only pond water.

It must be remembered that under these changing circumstances, in many cases farmers may have no choice but to grow rice simply to meet their household food needs.

So, what are the problems?

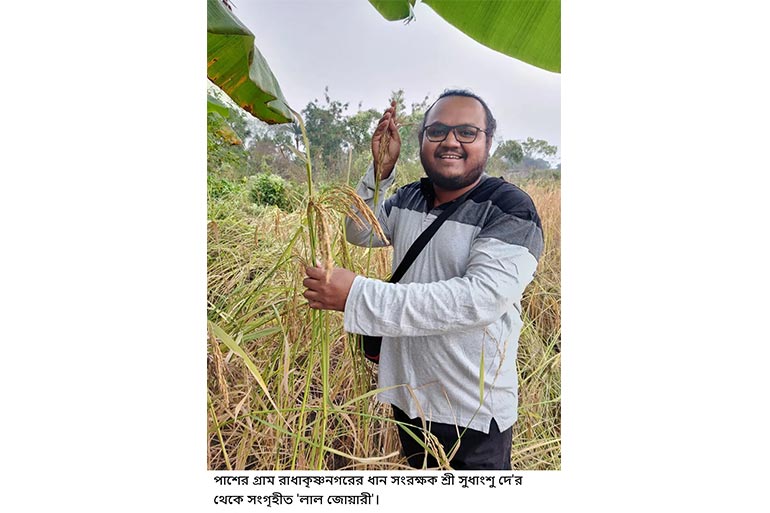

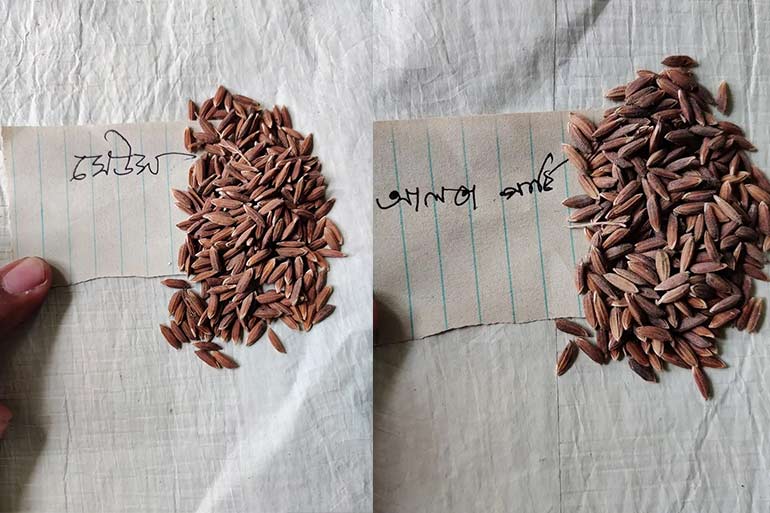

In such a situation, we felt that we should collect the indigenous rice varieties of the Sundarbans and build an archive. In that archive, each rice variety would be characterized and all related information recorded. That way, depending on high, medium, or low land; on rainfall, irrigation, or salinity problems; and on Aus, Aman, or Boro seasons, farmers would be able to choose the suitable rice varieties and cultivate them with confidence.

Yield?

Just as in parliamentary democracy everyone’s identity is reduced to being a voter, and in this ruthless age of capitalism everyone’s identity is reduced to being a consumer, so too in the post–Green Revolution era of agriculture we hear only one refrain: “Yield, yield, yield.”

But who eats all that extra yield? Who ensures that the farmer gets a fair price for it? Who takes responsibility for the fact that, in the race for higher yields, the soil is dying? Who answers for the fact that even with higher yields, farmers’ incomes are falling so low that many children of farming families have no interest in agriculture at all?

And can rice really be measured only in terms of yield?

Farmers are becoming increasingly isolated. Cooperatives have turned merely into money-lending institutions. Children of farming families see their parents toiling from dawn to dusk yet struggling to cover household expenses. As a result, they abandon agriculture and seek other livelihoods.

Government offices are preoccupied with insurance, schemes, and projects. Without conducting proper research on indigenous rice, work has once again begun in laboratories to develop hybrid varieties.

The obstacles to farmer unity remain unresolved because of a lack of leadership. Since income from farming is meagre, farmers try to sustain their households by taking on other kinds of work besides cultivation. Lacking formal education and much awareness of market politics, they often fail to recognize many of the conspiracies at play.

In such a situation, seeing industrialists build massive storage facilities, and witnessing contract farming by broiler companies in villages across the Sundarbans, one cannot help but feel alarmed.

So, will all the land be taken from the next generation under contract farming, and only cash crops be cultivated?

Large-scale monoculture farms have already caused tremendous damage to the soil. The small plots of two or four bighas, still held by marginal farmers, remain alive. These lands have immense potential and diversity. If such lands are collectively managed with proper planning, cultivating indigenous rice, fish, vegetables, and livestock, then, village by village, we can protect rural communities from the present crises of malnutrition, food insecurity, poverty, and severe decline in health.

This would also ensure the preservation of indigenous seeds while supporting farming. The dying rural economy would regain its strength. Capitalists have set their eyes firmly on food, as it is the most profitable for them. But this is actually dangerous. Any perceptive person can understand this. Before the capitalists patent all indigenous seeds, bring all lands under contract farming, establish processing centres in villages and extract everything away— we must very quickly take to the fields.

There is no more time!

(P.S. – By the time this piece is finished, all the paddy has already been harvested. Starting with 9 farmers, this year we will hand over several varieties of indigenous rice to at least 20 farmers. Primarily, they themselves have chosen the varieties according to the character of their land. For example, in Patharpratima, Bishnuda has chosen Malabati and Khejurchari; in Sagar Island, Shubhashis has chosen Maule; Manasidi has chosen Sitashal for the Aman season and Chomotkar for the Boro season. In this way, year after year, cultivation of indigenous rice must be expanded, plot by plot. Unless agriculture is freed from chemical fertilizers and poisons, our destruction is not far away!)

Author: Founder of Patharpratima Runners, an organization for indigenous crop cultivation and seed preservation.

Note:Translated by Debamita Ghosh Sarkar

To read the original Bengal article, please click here