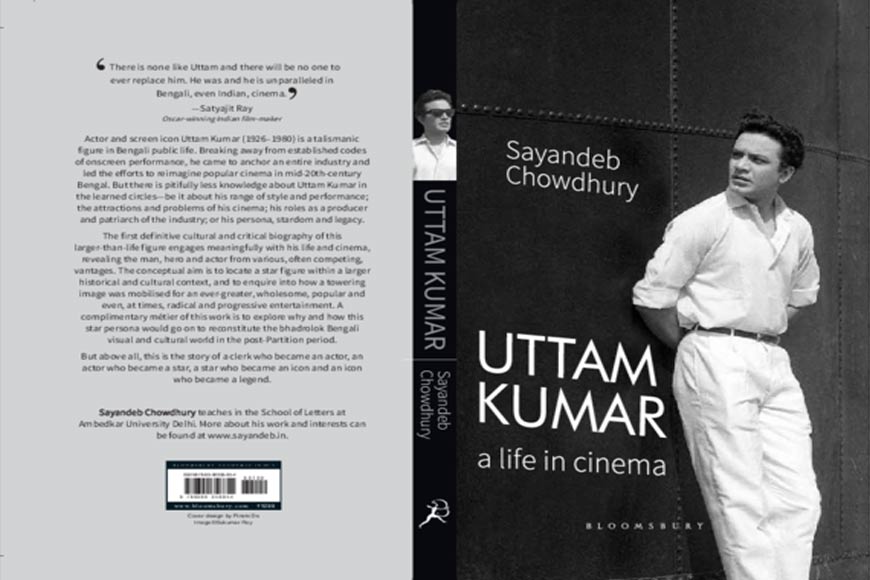

PUJO READ: Uttam Kumar --- A Life in Cinema; Bloomsbury

Not every Bengali will be on the streets this year pandal hopping, for there are many of us who love to spend a quiet Pujo, back home in the middle of books. GB recommends this particular book that features the man whose smile has swept generations off their feet. The man who dominated the silver screen after he debuted in 1948. His easy charm, smile, acting, made him a cultural icon and ‘Mahanayak’. He passed away on July 24, 1980, at the age of 53. Much has been written about his life and films. Recently published Uttam Kumar: A Life in Cinema by Sayandeb Chowdhury, published by Bloomsbury, is an addition to that list.

Here is an extract from the book. Read on:

When we combine the historical conditions with Uttam’s screen naturalism, a certain pattern seems to emerge. It was through Uttam’s screen persona that popular cinema announced its having arrived into an unambiguous present. Much of the magnetism of the 1950s melodrama lay in the incorporation of this self-assured figure, which came coupled with an identifiable, flesh and blood world inside the films; a credible script and a wonderful soundtrack.

But the most significant factor for the appeal of his cinema was the exploration of resolutions to the series of crises that could effortlessly interchange between what was desirable and what was realisable. Viewed closely, hence, a significant body of Uttam’s work was never an escape from the conditions of existence but a reminder that their inescapability was to be embraced with dignity. And what helped in the abutment of this liberal cause was the clever use of star value. Hence, as he became more confident, Uttam started playing roles with a more distinguished sense of belonging, characters with firm if polite conviction, where he could push the boundaries of social and moral one-upmanship.

And instead of creating any fissure, his move away from pure romances seemed justifiable and obligatory; even if he made occasional returns to romance throughout his career. A note of caution. Uttam’s cinema wasn’t always a template of recording the contemporary. His roster being of a staggering number, there were exceptions. So, the final verdict on the liberal quotient of Bengali cinema under Uttam is open-ended.

And instead of creating any fissure, his move away from pure romances seemed justifiable and obligatory; even if he made occasional returns to romance throughout his career. A note of caution. Uttam’s cinema wasn’t always a template of recording the contemporary. His roster being of a staggering number, there were exceptions. So, the final verdict on the liberal quotient of Bengali cinema under Uttam is open-ended.

But it is certainly a fact that several portrayals of Uttam were closer to a broader humanist (and unabashedly middle-class) appreciation of the present than to any reactionary, paternalistic nostalgia for a mythical, pre-modern past. This aspect is highlighted in The Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema, which says that Uttam Kumar’s early romances re-invigorated the bhadralok, apolitical humanist literary tradition in cinema while at the same time “abandoning the many conservative tenets of that same tradition”. This was the underlying algorithm of the bhadralok figuration. But there was more.

A defined bhadralok aspiration as such was not to be achieved through a tenacious imagination of escapist romances. Instead, the apparently self-sustaining world of Uttam’s romances is constantly poked at by hunger, crises of religious and caste identities, anxieties of employment, class conflict, homelessness, conjugal one-upmanship, dignity of labour, threats of social boycott and the uneasy cohabitation in the Bengali milieu between love actually and social sanction of marriage.

Resultantly, the films showed significant transgressions from formula to accommodate emancipatory exertions in the meaning of citizenship, identity and couple-hood. This is precisely why there is a need for a corrective, revisionist estimation of Uttam’s films, which would help us break away from the comfortable, conventional coupling of romantic drama and stardom.

Uttam’s stardom was something that the popular industry had meticulously invested in, partially obscuring these productive tensions. But we must see Uttam’s real ascent to stardom as part of this appreciation of and complex encounter with modernity, something barely visible when an entire system was trying to piggyback on a star’s charismatic proficiency. It is hence no accident that even in the apparently formulaic romantic melodramas, where the profession of the leading man is hardly a matter of scrupulous audience deliberation, Uttam plays doctor, scientist, engineer, architect, lawyer, radio singer, industrialist and so much more. All of these professions/livelihoods were entrenched in an appreciation of a thriving urbanity, referring to the broader embrace of modernity in Nehruvian India. So, in spite of romances having cultivated the out of-reach stardom of Uttam, his persona, was at the same time of an identifiable, omnipresent, next-door variety.

Much of this range was visually achieved in letting Uttam’s screen persona appear in sartorial codes—from rolled-sleeve formal shirts, ties, pointed shoes, tuxedo and three-piece suits to loosely-worn kurtas, homely singlets and light, cotton dhotis. To that end, he was not a star whose celluloid allure obscured the demanding environs of the world around but actually made them more bearable.

So, even if he could never completely eschew his mannerisms, so typical of the acting cultures he inherited, he could put all his performances into neatly divided and appreciable identities, which spanned almost every aspect of middle-class life. No single entity in the history of the whole of Bengali culture has so neatly embodied the imagination, anxieties and fetishes of the middle class. It is at this cusp that the unmissable bhadralok sensibility of his cinema aligned itself unequivocally to the transnational star imagery of his persona. Hence, if one part of Uttam— the Hollywood-like stardom—can be gauged through the imported form of the melodramas; the other part—his downright identifiability—can be gauged only when one is keyed into the very Bengali reworking of the transnational form. One cannot hence see Uttam as either star or a screen bhadralok. He was both of them equally while each constituted much of the other. And this fact alone gives his phenomenal, boisterous stardom a refined and genteel embellishment. One must not think that one film or character individually presents this convergence of the bhadralok and the star.

There was, rather, an organic interchangeability between the two, which matured over time and emerged as a cumulative figuration. This was both the genesis and continues to be the best reason behind Uttam’s immortal appeal.