Rammohan remembered: Sati and Antarjali Jatra

Sati is a Sanskrit term which means ‘a wife who possesses great virtue’. Agehananda Bharati, the late Austrian-born anthropologist who was born Hindu, said that sati was the nicor (essence) of pativratadharma (moral action appropriate for married women) The sati concept was so popular at one time that it was used as a prefix to a woman’s name to denote extreme devotion to the husband, admired by men and women alike.

There have been cosmetic changes in the situation in India today, both within cinema and in rural areas. Earlier sati films include Sati Madalasa and Savitri in 1932, Sati Mahananda in 1933, Sati Anjani, Sati Seeta and Soubhagya Kankshini in 1934, Sati Sulochana and Toral in 1935, the box office hit Sati Anasuya in 1943. This trend continued into the early 1950s. Sati Annapoorna, Sati Vaishalini, Behula, Savitri and Mahasati Anusuya were made in the late ’50s. Direct sati stories then became less frequent though modernised versions of these devoted wives continued.

In the 1980s, two significant films that analysed the practice in two different ways are Aparna Sen’s Sati (1989) and Goutam Ghose’s Antarjali Jatra (1987). Both are contemporary filmmakers distinguished by memorable films exploring significant social issues through cinema.

Sati, Aparna Sen’s third film, written and scripted by her, proves to be a ‘rupture’ in the continuity of the logic of “autonomous choice” she espouses in her other feature films. In her other films, the underscoring of women’s agency is closely allied with access to ‘voice.’ In Sati, the woman is genetically stripped of ‘voice.’ She is mute, an orphan and offered shelter, food and clothing from a poor uncle and in exchange, she is like an unpaid servant in the family. So, she is marginalized socially, biologically and economically. As her horoscope states, she will be widowed on marriage, an outlet is sought through marrying her to the huge tree near their home. Naïve that she is, she considers this tree to be her husband and loves it dearly.

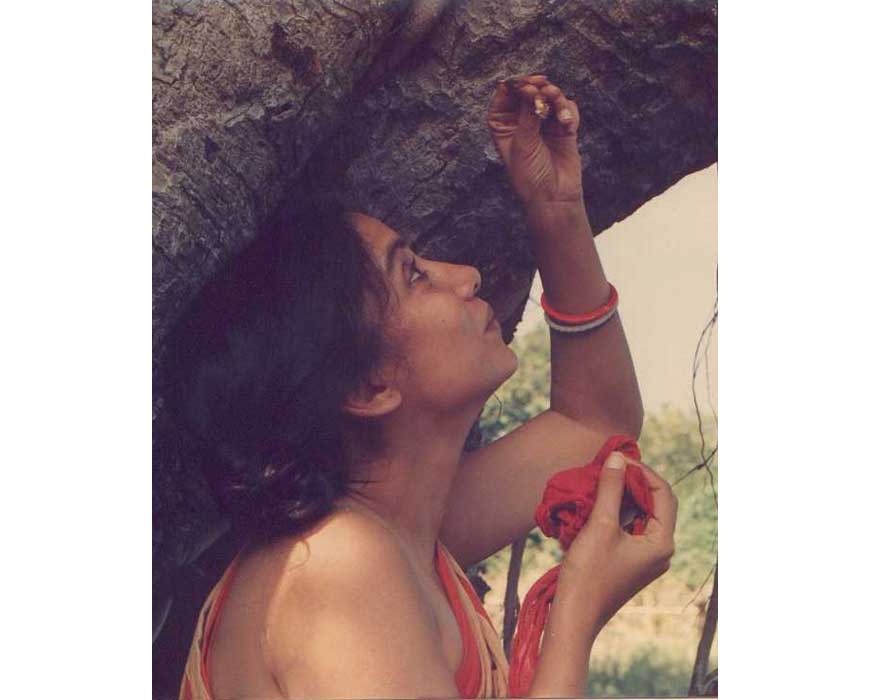

Sati with Shabana Azmi as Uma

Sati with Shabana Azmi as Uma

Sen, either by design or incidentally, also unfolds the tragedy of power versus the lack of it. Her celebration of Uma’s sahamaran with her tree-husband evolves both into a comment on and a critique of the socio-religious custom of sati indulged in by a majority of Brahmins in Bengal in the 18th and 19th centuries. Uma’s sati counteracts and contradicts every rule in the sati book.

Antarjali Jatra based on a story by Kamal Kumar Majumdar is set in 1832, immediately after the abolition of sati in Bengal. The story revolves around a ‘potential’ sati when an octogenarian Kulin Brahmin is brought to the crematorium just before he is to die. He is married off hurriedly to a young girl named Yashobati at the burning ghat itself, so that the girl’s father, an impoverished Kulin, can liberate himself of the ‘guilt’ of failing to marry his daughter off to a Kulin groom and that too, without the burden of a dowry. He promises the pandits that his daughter will commit sati the moment her husband dies. The marriage is conducted at the burning ghat and Yashobati, decked up in bridal finery, waits to become a sati as soon as the husband dies.

Yashobati is left alone with her dying husband, with only the chandal (the untouchable ghat-keeper, cremator of corpses) for company. When the chandal persuades her to run away, she refuses in spite of the fact that death confronts her and she dreads it. She tends to her dying husband who revives under her care. The chandal castigates her squarely. Yet, with time the two are physically attracted to each other and become lovers. The river gets flooded, taking the bier with the dying man away with its torrential waters. Yashobati swims out in search of her husband, only to find an empty bier. She drowns in the flooded rivers of the Ganga, defying death of the sati by fire, while at the same time, conforming to the custom by dying when her husband does, and through the same agency – water, not fire.

Unlike Sen in Sati, Ghose falls back on the stereotypical ‘narrative of rescue’ pointing out the difference between two directors on grounds of gender, never mind that the ‘narrative of rescue’ is blurred beyond recognition. The other point of difference between Sati and Antarjali Jatra is that Uma is plain looking but Yashobati is portrayed as beautiful. The obsessive male gaze, directed by the husband, the male lover and the director of the film at the female body is inevitably sexual. But it is also a reminder that the same body will burn. The male gaze does not exist with reference to Uma in Sati though her body too, is ultimately destroyed through death.

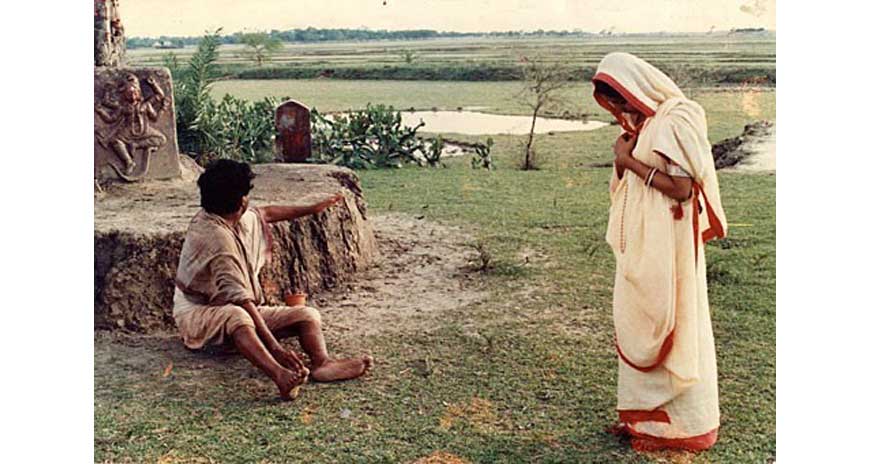

Antarjal Jatra

Antarjal Jatra

While Antarjali Jatra blatantly foregrounds the body of the woman, Sati keeps it beyond the cinematic space and characteristically low-key for Uma, the protagonist. Yet, both Yashobati and Uma are ‘sacrificed’ through natural calamities. Water defines itself as an agency of death for both women. Both Uma and Yashobati belong to extremely impoverished Kulin Brahmin families, though their victimization is distanced in terms of their class, backdrop and in their power of articulation. Uma is mute. Yashobati is not. Uma is an orphan. Yashobati is not. Yashobati has the ability to exercise her choice – in her love-making with the chandal as well as in her choice of rescuing her dying husband from the floods and thereby, underwriting her own death.

Uma has never learnt to articulate her choice because she does not have a choice. She is born into a life of genetic silence. When compared with Yashobati, she is more vulnerable and therefore, has no power. Yet, in the ultimate analysis, they must both die because they are hopelessly trapped into a birth into a family over which they have no control. They are born and bred in desperately poor Kulin Brahmin families where poverty is a greater curse because of their high birth and not in spite of it.

The question is – why, in either case, is a woman called upon to pay the ‘price’ of this high-caste-poor–circumstance background with their lives? Did Yashobati really have the choice to run away? Did she really try to rescue her husband from a watery death because she loved him? Or, because he was her husband? Neither, it was just instinctive because she knew she could never have run away. She had no place or no one to run away to. She could not have run away with the chandal because the differences in their social circumstances precluded this possibility. Nor would the chandal be able to ‘rescue’ her from her plight because he was already victimized by his low caste and his untouchablity. She tried to rescue her husband because she was conditioned to imbibe duty to husband before anything else. So, in essence, her ‘choice’ is no better than the lack of choice Uma has.

Both Uma and Yashobati therefore, are objectified as women. Yashobati asserts her subjectivity just once in the film – when she enters into the single sexual liaison with the chandal. The irony here is that she is married off to a dying and doddering old man to ‘liberate’ her father from ‘sinning’ – only on grounds of the high caste they belong to. Yet, her sexual initiation has to take place through an untouchable – the lowest rank in the caste hierarchy – a chandal. In Sati, Ashok, a Kayastha, lower in the caste hierarchy than the one Uma is born into, initiates Uma into sex. Both liaisons are rooted purely in sex because Yashobati’s loyalties still appear to lie with a husband she does not even know and who is already dying. Uma’s loyalty lies with the tree she is married to. Antarjali Jatra is a scathing comment on the social system within the dynastic Kulin Brahmins in 19th century Bengal. But the comment is interwoven with an emphasis on the body of a woman.

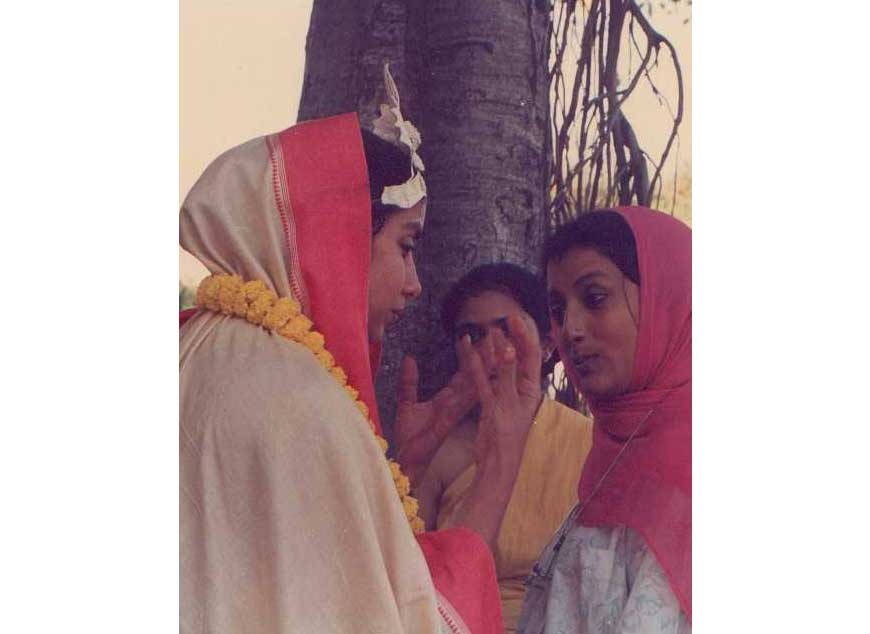

Sati working still

Sati working still

One important quality that binds Sati and Antarjali Jatra is that both are contemporary films in Bengali marked by a historical and sociological distance from sati as practiced in Bengal 150 years before these films were made. This distance makes possible a materialist analysis of sati based on contemporary historical and sociological researches.

Neither film seeks to resolve the problem through relocation of the narrative through flash-forwards or other cinematic strategies. Neither film offers alternative solutions to the crises. Both films have tragic closures and end with the death of Uma and Yashobati respectively, struck down by Nature in the prime of their lives. Looked at from a completely different perspective however, their deaths arrive as ‘liberating’ factors for them because – given the time, the place and the society they lived in - had they not died as they did, what ‘life’ would they have had left to live?