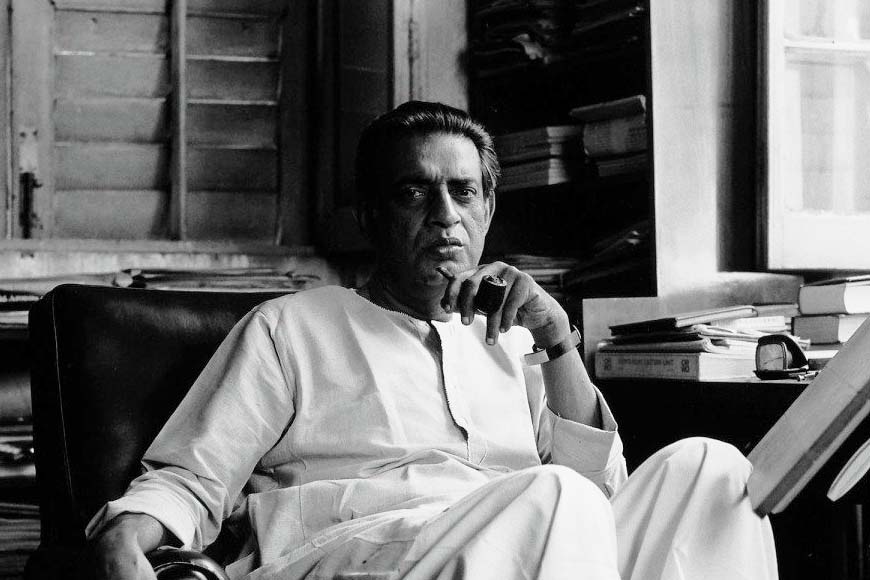

Satyajit Ray, hunger, and Pather Panchali

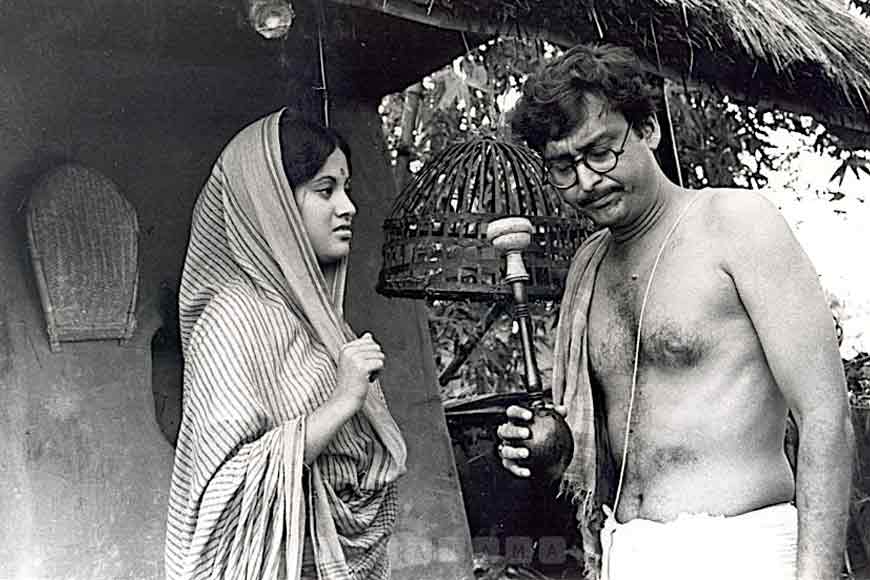

WHunger finds a prominent place in three films by Satyajit Ray, reflecting three completely different backdrops, though hunger is a significant sub-plot in all three narratives, each one a ‘period’ piece in a manner of speaking. One is Pather Panchali, the second is Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, and the third is Asani Sanket.

However, it is in Pather Panchali that we see hunger at its starkest. The dented brass vessel that the doddering aunt Indir Thakrun carries with her defines the abject despair of the old woman’s impoverished, unwanted life. Indir is introduced with a close-up of a brass bowl filled with some mishmash, and then the camera tracks back to show the bent, toothless woman eating from the bowl. The vessel that holds her water suggests the reality of her tragic death as it tumbles down the stones noisily, suggesting that she is no more.

While she was alive, the two children, Apu and Durga, loved her “not so much because she was their aunt, as because she represents a mysterious force of life and death that fascinates them through her stories of the witch and other fairy tales. It is only when her own children’s survival is at stake that Sarbajaya turns her face against the old woman, and she dies like an animal”, writes Chidananda Dasgupta in The Cinema of Satyajit Ray.

Interestingly, Ray does not focus on this brass vessel much, so we do not pay attention to it either. It is only when she dies and it tumbles down the rough slope at the unwitting touch of Durga that the camera closes in and follows its movement until it splashes into the water, and we see that it is badly dented, much like the life of its owner. It drowns when its owner dies, as unceremoniously as Indir does. In one scene, Sarbajaya sees Indir sneak into the kitchen. When she comes out, Sarbajaya asks her what she was doing. Indir shows her two green chillies. Durga, who is fond of the old woman, offers her a brinjal.

In another scene, Indir returns from a relative’s house back to Harihar’s home. She asks for water when Sarbajaya is having lunch. The younger woman asks her to get it for herself as she has the brass vessel with her. Indir fills water into the vessel, waits for a few minutes to watch Sarbajaya eat, flashes a toothless smile in the faint hope that the younger woman might give her something. But when this does not happen, her smile disappears. She moves away to her small perch, pours the water out into the ground, emptying it. Asking for water was just an excuse to get some food. When this does not come, the water is of no use to her. This time, the dented vessel becomes an ‘agency’ for her to express the pain of rejection, loneliness, alienation.

Indir is thrown out by Sarbajaya twice during the film and each time, she packs her belongings - a tattered straw mat and a small, dirty, wretched bundle that tells its own story. When she comes back the second time, we see her walking with a stick for support and wearing an old, weather-beaten shawl. Sarbajaya rebukes her for having ‘begged’ for the shawl, but does not take it away from her. Within the poverty-stricken family of Harihar, Indir’s position is the worst because no one quite wants her around except Durga. Apu is too little to understand what it is all about.

Pather Panchali is scattered with items of food. Little Durga hides a guava she has stolen from the Mukherjees’ garden inside an earthen pot under a bunch of bananas. When Apu grows up to go to the village school, which is also the local grocer’s shop, we find him drinking milk from a big bowl and as he finishes it, some milk trails down the corners of his mouth. We never see Durga drinking milk.

At the grocer’s shop laden with different items of food, a little girl arrives to ask for a paisa worth of puffed rice. A visitor arrives at the shop and after some small talk, manages to wean away a small bottle of cooking oil from the grocer for free. Just before the famous train sequence, we find Durga chewing on a stick of sugarcane and she hands a piece to Apu later on as they walk through the kash fields towards the sound of the approaching train.

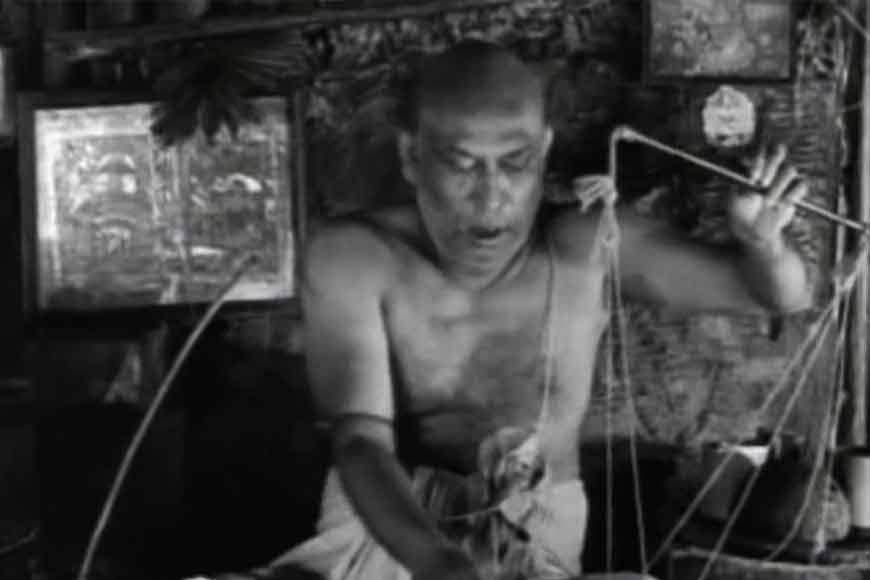

Durga tends to sneak away whatever item she can, especially food. She listens neither to the warnings of the Mukherjees nor to her mother’s threats, and keeps stealing guavas and raw mangoes from their garden. She makes a pickle-like mix and shares it with Apu on the sly, warning him not to tell their mother. With her friends, she organizes a festive ‘picnic’ near their house and the children cook real khichuri (mishmash of pulses, rice, vegetables) over a wood fire, and even have a spat over who was to bring the salt and the cooking oil. Food, its material and allegorical qualities, its physical and time-centered consumption and appropriation, plays a critically significant role in poor and low-middle-class, rural Indian families even today.

In one scene, Sarbajaya asks Durga to fetch molasses worth two paise because she wants to make payesh (Bengali rice pudding) for Apu. Durga knows it is only for her brother, but she has normalized the preference given to him. She loves him very much. The famous scene where she eggs Apu on to follow the sweet vendor with his treasure trove of sweets right to the home of her affluent friend, is another example of her craving for food.

The children enjoy the fragrance of the sweets and follow him in the hope that wherever he goes, they might get to sample some. A stray dog follows them too, and we see their shadows in the pond running beside the muddy road. Does this mean that Durga is a glutton? No, she is deprived of basic food. This sneaking into the neighbour’s garden feeds her hunger and at the same time, brings some adventure into her bleak life.

The references to kinds of food, not the modern, manufactured, packaged, sophisticated brands but organic food - cereals, vegetables, fruits, milk, molasses, rice, puffed rice, spinach - in Pather Panchali do not symbolise the beauty or decoration of the setting, but subtly throw up the underlying theme of poverty in Harihar’s family, accompanied by decay and hunger in its varied manifestations. The film is in black and white, so the food is stripped of the glamour of colour.

One does not find Apu stealing fruits, only Durga does it. Only once in the entire film do we hear of fish Harihar has brought home from the market. The allegories bring out their poverty, making us wonder whether it will ever go away from the lives of Sarbajaya, Harihar and Apu.

The ‘objects’ in the film - from the tattered shawl of Indir with a huge hole in the middle, to the chain of beads Durga stole from her friend, the tattered sari Sarbajaya wears when there is no news from Harihar for five long months and nothing in the house to eat - are all symbols of hunger and poverty, leading to a decay in human lives.

In Pather Panchali, food is so visibly and verbally significant that it throws into relief the ‘lack’ of other concrete objects of use or nostalgia that are subtly present. One example is the hand-fan Sarbajaya uses to fan the burning embers of her earthen oven, or to shoo away disturbing elements, to fan her husband Harihar when he sits down for lunch, and only once, to fan herself with as she rests on the earthen floor of the small compound.

For Sarbajaya’s family, food is everything and their lives revolve around the uncertainty of food in their everyday lives. When no food is left, we find Sarbajaya digging out some brass plates and a bowl she takes out quietly at the break of dawn to pawn off secretly so that she can buy food for the children. This is captured through a collage of shots without dialogue, but with natural sounds of the vessels being taken out, the door being shut and Sarbajaya walking out and coming back.

This hunger expressed through food is gender-specific. Sarbajaya is left to deal single-handedly with hunger consequent to a lack of food that spells poverty at its scariest extreme. The one time we see Harihar eating, his plate is filled with a small ‘hillock’ of rice. Yet, the camera rarely closes in on items of food or dwells on them except in passing. For example, in the picnic scene, we see that something is being cooked, which is later eaten, but we never get to see the actual dish.

In the one scene that shows Sarbajaya having lunch, the camera keeps away from the act of eating and keeps it in suggestion, focusing on Indir’s face. There are constant hints if one can catch them, about the consumption of food or rather, the lack of proper and adequate food shown only through Durga’s childish pranks of stealing fruit or following the sweets vendor on his journey. During Durga Puja, there is a shot where children crowd around when prasad is being distributed out of a big basket, a normal incident in Bengal villages during the time in which the film is set.

Ray always found magic in the everyday, and meaning in simple human affairs. And like a true Bengali, he saw food as a way to depict his view of humanity.