The 18th-century Russian who drove the birth of modern Bengali theatre

In this two-part series, we explore the history of modern Bengali theatre, beginning at the end of the 18th century, when a Russian Indologist and a few of his Bengali friends planted the seeds from which would sprout a flourishing tree.

Through the heart of Kolkata, adjoining some of the city’s most iconic structures, runs Gerasim Lebedev Sarani. For those scratching their heads, this is the thoroughfare we call Cathedral Road, quietly renamed some five years ago after the remarkable Russian adventurer, linguist, musician, writer, and Indologist Gerasim Steppanovich Lebedev (sometimes spelled Herasim Lebedeff).

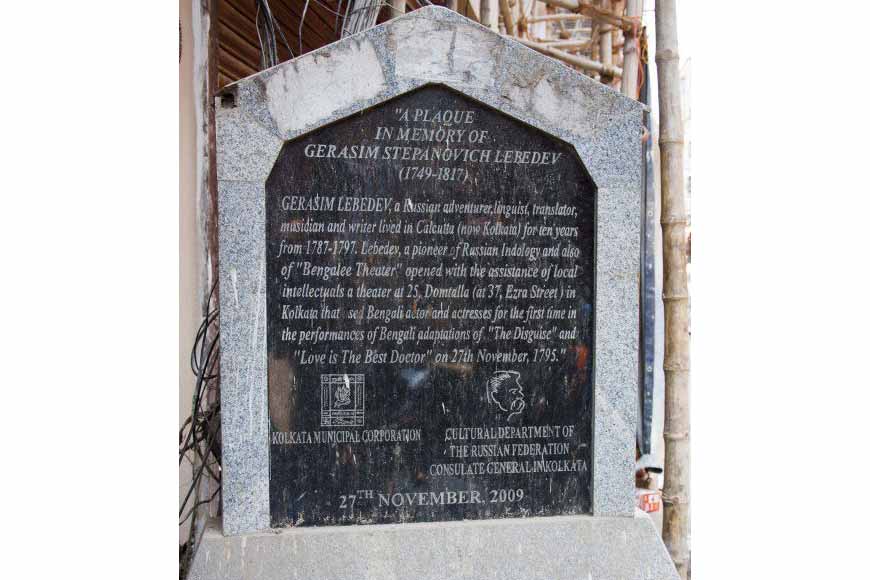

Sadly, so quiet was the renaming that most of us probably missed it. Even more of us have probably missed the plaque in Lebedev’s memory, which has stood on a particularly cluttered and dingy stretch of Ezra Road since November 2009.

And yet, it would be fair to say that this is the man who, during a mere 10-year sojourn in Calcutta from 1787-97, laid the foundation of what was to become modern Bengali theatre. Having arrived in the city from Madras, Lebedev rented a house from one Jagannath Ganguly on 25, Doomtola Lane (later 37-39 Ezra Street), and in a matter of months began transforming it into an auditorium for theatrical productions.

Before we proceed further, it is important to note that theatre as an art form was already well established in Bengal, thanks to the age-old tradition of folk theatre, used extensively to propagate critical social, political and cultural messages. As an indigenous art, folk theatre breaks down the rigid barriers set by the Natyashastra, the ancient Sanskrit treatise on the performing arts most commonly attributed to the sage Bharata, though scholars say its authorship is unknown.

Bengal never strictly followed the tenets of the Natyashastra anyway, leaning more toward styles such as ‘Odra-Magadhi’, characterised by grandiose dialogue and rhetoric. There were other traditional theatrical styles, too, including Katha Natya (where a single performer known as ‘gayen’ or ‘kathak’ narrates a verse or prose with vocal and musical accompaniment), Nata Geet (character enactment accompanied by chorus/orchestra), Kavya (a type of imitative dance with an interplay of dance and song), Chitra Ranga Kavya (composition involving several ragas), and Bhani (instrumental music and dance).

Certain hybrid forms, such as ‘Kabigaan’ or ‘Potuagaan’ (mostly music-based), and puppetry were also in vogue. There were also the highly popular ‘Shong’ performances, loosely a form of street theatre where a stock character would satirise various personalities or social issues through song and dance, especially during public festivals. A highly effective, if sometimes crude form of expression, Shong gradually lost its position and was replaced by the ‘Panchali’.

Finally, the traditional musical theatre known as ‘Jatra’ was, and still is, immensely popular, especially in rural and semi-urban Bengal. Having evolved from primarily mythological themes to more contemporary ones, ‘Jatra’ remains a multi-crore rupee industry employing more people than the film industry and urban theatre combined.

All of which meant that the multi-talented Lebedev had a ready pool of performers and themes to choose from. However, the Russian Indologist, who had learned Bengali during his stay in the city and had become the first person to use Indian tunes on Western musical instruments, chose to deviate from tradition. He translated Richard Jodrelle’s The Disguise and Moliere’s Love is the Best Doctor into Bengali with help from his Bengali tutor Goloknath Das, built the aforementioned theatre at his own expense in 1795, and trained an ‘all-native’ cast to act. And so it was that the first Bengali performance of The Disguise was staged on November 27, 1795.

This also marked the launch of the first native proscenium stage, ‘The Bengali Theatre’. Lebedev himself composed the music for the play, with lyrics borrowed from Bharatchandra Ray, the author of Annadamangal. Also for the first time, women from the city’s red-light quarters were given an opportunity to play female roles, traditionally mostly played by men since it was taboo for ‘decent women’ to appear on stage. The production was announced through advertisements in the Bengal Gazette, with tickets priced at Rs 8 for the boxes and pit, and Rs 4 for the gallery.

Lebedev followed this up with a staging of Love is the Best Doctor in Bengali on March 21, 1796. According to theatre scholar Kiranmoy Raha, “The 200-seat house was ‘overfull’ on both nights; but Lebedeff left India soon after, and his pioneer efforts bore no fruit.” That last bit is not perhaps entirely accurate, for Lebedev did leave an imprint on the city’s theatrical map, by proving that there was a large, paying audience for modern, Western-style theatre in the local language, a fact that had escaped the British, who had set up English theatre houses in the city for their own entertainment, not bothering with what the ‘natives’ wanted.

In fact, Lebedev’s abrupt departure was due in no small measure to British resentment. Jealous and angry at the stir he had created with the ‘native’ theatre, two Englishmen set fire to his auditorium, completely destroying the stage. A hostile British administration, infuriated by his sympathy for Indians, finally expelled Lebedev from India in 1797. Virtually bankrupt, he eventually made his way back to Russia, and once back in St Petersburg, compiled a small Bengali dictionary, wrote a book on arithmetic in Bengali, translated part of Annadamangal into Russian, and even wrote to the Russian ambassador in London about publishing Bharatchandra’s works in Russia.

Following his departure, there was a temporary lull in Bengali theatre, but a new urban class had emerged in the city through exposure to Western education, who were Indians by blood and colour, but English in tastes, opinions, morals and intellect. This emancipated class of Bengalis was instrumental in transforming and reviving vernacular theatre, as a number of public theatre halls came up one after another.

(To be continued)