Uttarpara archive celebrates 99 years of Mrinal Sen with unique tribute

Tucked away in one corner of Uttarpara stands Uttarpara Bengal Photo Studio, the brainchild of 41-year-old Arindam Saha Sardar. A self-taught archivist and restoration artist, Arindam makes biographical documentaries, curates exhibitions of rare artefacts, collects old still and movie cameras, Bengali magazines of yore, and anything else of archival interest. Back in 2008, he founded Bengal Studio in a rented garage in Hindmotor, but when the family relocated to Uttarpara in 2010, Bengal Studio found a permanent venue on the ground floor of their residence.

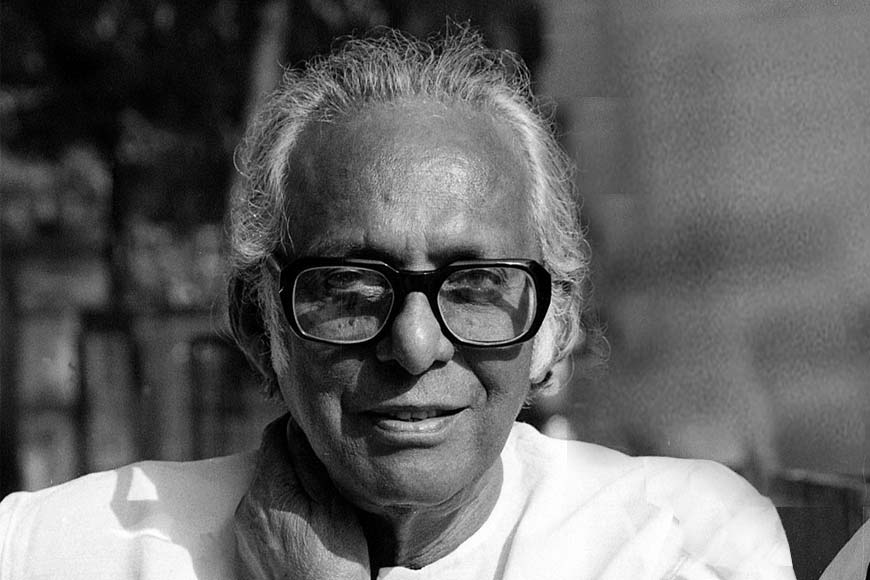

Sen represented an era that survives and reflects itself through him - the lone ranger on a track now filled with other people, other cinema. His alacrity and nervous energy continue to amaze, his speech spiked with typically barbed smiles and caustic one-liners still makes for wonderful anecdotes.

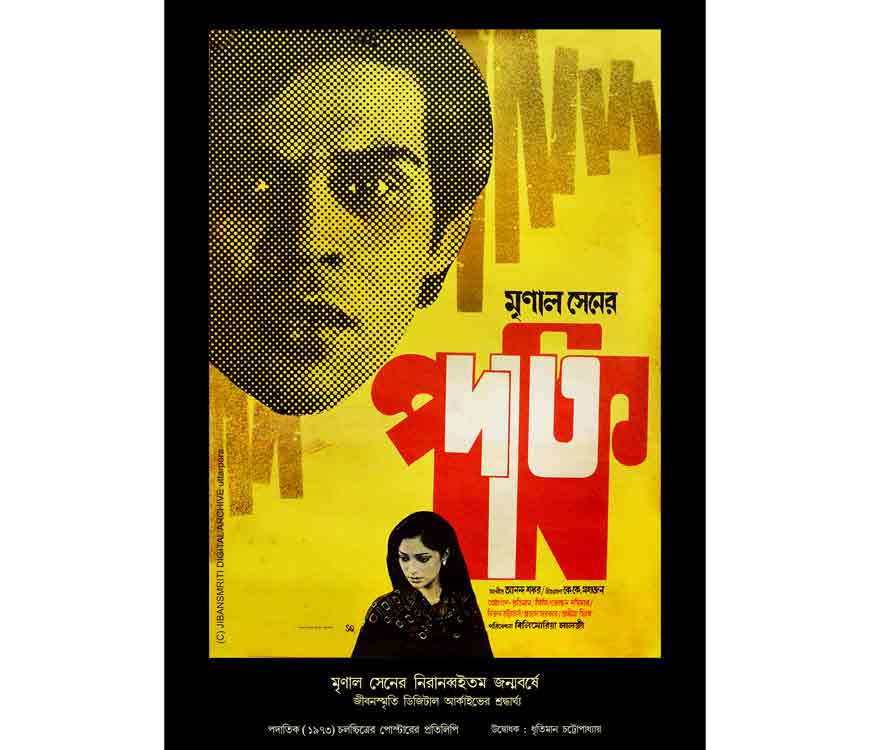

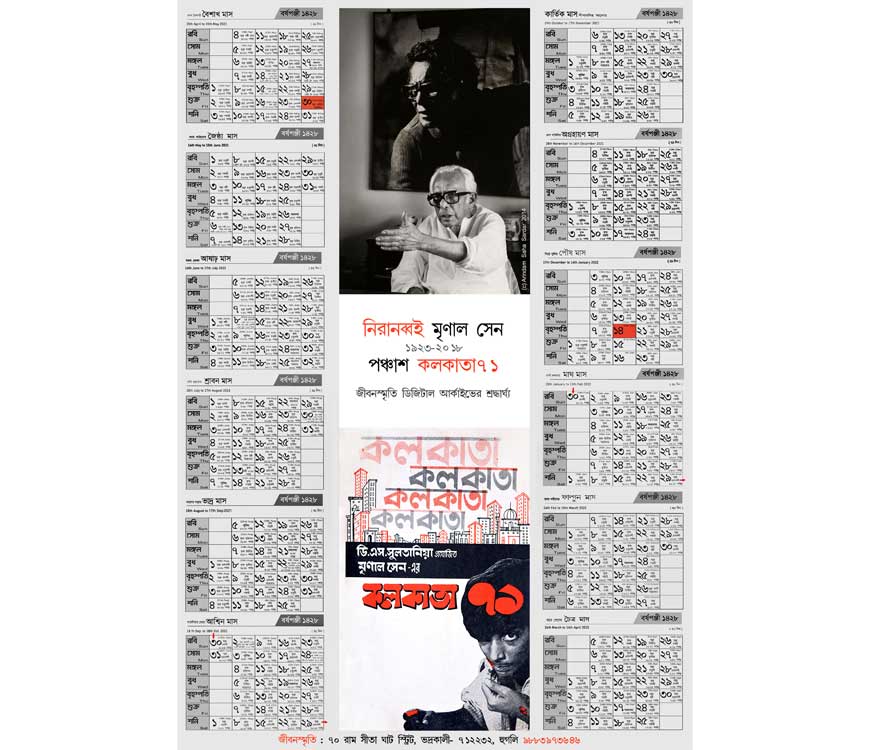

Over time, Arindam has built what he calls the Jibonsmriti Digital Archive, an outstanding effort to preserve the best of Bengal’s culture including, of course, its cinema. This year, to mark iconic filmmaker Mrinal Sen’s 99th birthday, which was yesterday, Arindam is putting up an exhibition of everything Sen stood for through his films, his lifestyle, his ideology, and his social interactions. This includes the release of a Bengali calendar with a black-and-white image of the filmmaker, and the original poster of Sen’s film Padatik.

Mrinal Sen Poster Padatik Jeebon Smriti Archive-2021

Mrinal Sen Poster Padatik Jeebon Smriti Archive-2021

The virtual launch of the calendar will be done by Kunal and his wife Nisha Ruparel Sen, while the poster and booklet of ‘Calcutta 71’ will be released by actor Dhritiman Chatterjee.

Sen represented an era that survives and reflects itself through him - the lone ranger on a track now filled with other people, other cinema. His alacrity and nervous energy continue to amaze, his speech spiked with typically barbed smiles and caustic one-liners still makes for wonderful anecdotes. On a visit to Bangladesh to prepare for ‘Amar Bhubon’ (2002), Sen visited his hometown and the place where an infant sister was buried. “It was a trip back to nostalgia. The tragedy had happened a long time ago. But when I reached the place, I broke down,” he recounted.

Mrinal Sen

Through each film made over four-odd decades, Sen managed to disturb his audience and stir them into introspection, question, and debate. He experimented with the non-narrative form in ‘Chorus’ (1974) and ‘Calcutta 71’ (1972). But these received a lukewarm response from audiences who were perhaps conditioned to Sen’s angst unfolding through a story, or incident, or character, such as ‘Ek Din Achanak’ (1989), ‘Ekdin Pratidin’ (1979) and ‘Bhuvan Shome’ (1969). ‘Khandhar’ (1983) blended to produce a different, cohesive whole, as seen in ‘Antareen’ (1993). These are based on original literary works by noted writers. Sen was one of the first filmmakers in India to make films in languages he did not know, such as Oriya and Hindi, because he did not believe in confining his creativity to a linguistic identity.

Arindam built his Mrinal Sen archive in 2017-2018. Following Sen’s death in December 2018, his son Kunal “very generously donated many documents and other materials belonging to Mrinalda in 2019”. These include Sen’s personal collection of books in Bengali and English on cinema, politics, history, and art, totalling nearly 425 books and magazines; 250 shooting stills from Sen’s films, the still portrait of the horse used in ‘Ek Din Achanak’, and a wooden bookshelf to stock all of it, says a delighted Arindam.

Arndam Saha Sardar

Arndam Saha Sardar

Mrinal Manjusha Museum is the name he has chosen for this special section, and it will be housed in the new apartment that Arindam has bought. The plan is to have a virtual launch on Sen’s 99th birth anniversary, followed by a big event next year to mark his centenary. This year, viewers can watch Arindam’s documentary ‘Ami Mrinal Sen Ke Dekhini (I Have Not Seen Mrinal Sen’.

His collection also includes videos and stills of Sen dating back to 2011, and three hours of Sen’s interviews on film, from 2013-14, besides stills gathered from other years. Film scholar, author and historian Someshwar Bhowmik has donated a two-and-a-half-hour audio recording of Sen’s interview from way back in 1987.

Also read : The Mrinal Sen films we can no longer watch

Arindam has also painstakingly collected articles, interviews, and essays on Sen published in the media over the years, and digital copies of all his films. Kunal, who lives in Chicago, says, “Jibansmriti took some of his photographs, small pieces of furniture, and other personal items. They have a rich collection of video interviews of many people associated with my father, and they plan to create a larger archive soon.” The archive is still growing and will continue to grow.

Mrinal Sen Bengali Calendar

Mrinal Sen Bengali Calendar

The collection includes original editions of all the books written by Sen, copies of all his articles published in different magazines and newspapers, original screenplays, and a massive hoard of photographs of actors, technicians, music directors who worked with Sen, as also photographs of his family. These are now being collectively digitised to become a permanent part of Arindam’s larger archive.

Arindam built his Mrinal Sen archive in 2017-2018. Following Sen’s death in December 2018, his son Kunal “very generously donated many documents and other materials belonging to Mrinalda in 2019”.

Researchers and film scholars are invited to use the digital library either virtually or physically on payment of a nominal fee. A huge catalogue is being built of interviews of actors and technical crew who Sen worked with. Researchers will also have access to the collection’s evolving catalogue, the list of Sen’s films and photographs, letters, song booklets and so on.

Kunal Sen and Arindam Saha Sardar

Kunal Sen and Arindam Saha Sardar

Kunal says, “Film Heritage Foundation agreed to keep many other artefacts, including some of his national awards, his Dadashaheb Phalke medal, and some large framed pictures from our flat. I should also mention that they manage their archive as well as any international organization, both in terms of infrastructure and knowhow. Unfortunately, there is nothing like that, or even close, in West Bengal. I also promised a few things to Stanford University in USA, and Jadavpur University, but the Covid situation has slowed things down.”

He adds, “I finally transferred all the archivable materials that my father left behind to the University of Chicago Library. Either because of his deep distrust for nostalgia, or simple laziness, he did not take care of any documents. During his life he threw away all letters, all his screenplays, all his manuscripts. So what I could finally gather was very little - some correspondence between us, a bunch of photographs, and some of his awards.”