When Politics, Realism, and Humanity shaped a New Wave - GetBengal Story

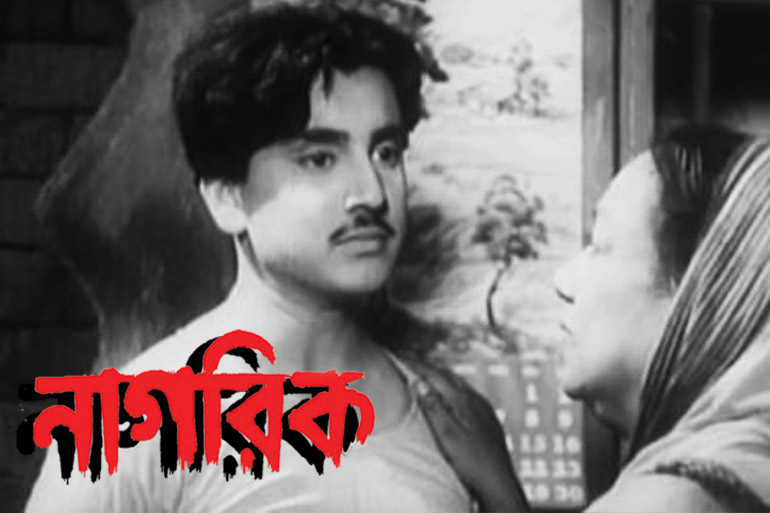

In 1972, at the time of his last film Jukti, Takko aar Gappo, when Ritwik Ghatak himself would say, “I have no theory” or “I don’t believe in slogans in cinema,” it is remarkable that the very same person’s first film as a director was an unmistakably leftist, politically outspoken, and direct work: Nagarik (1952). Emerging from the group theatre of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), this film marks the first time a committed communist-socialist writer-dramatist wielded cinema as a medium.

In 1956, while editing Aparajito at the Bengal Film Laboratory, Satyajit Ray discovered the print of Ghatak’s first film. Ray wrote: “We watched the film immediately. It was made under very difficult circumstances, and it shows—there’s practically no polish at all—but even so, I found certain qualities that inspired a deep respect for this young director.”

The film opens with the camera capturing the sky, then descending to the earth and the river. This river is a golden line of dreams, not the beloved Titash. Ghatak’s off-screen voice narrates: “Silently flowing along the hard iron dam, beside the factories…”—a trace of industrialization alongside the neglected city river. His voice continues, “I knew him, I had seen him. Standing there, the metropolis.” From the sky and the river, the camera descends to the concrete, to the flow of people: “…I had seen him, among countless citizens, a single citizen.”

When Nagarik was made in 1952, it was released only after Ghatak’s death in 1977. At the time, the twenty-seven-year-old Ghatak had been active in IPTA for about a year, earning recognition in theatre. Alongside group theatre work, he was writing his own plays, translating works, and more. Naturally, this directly influenced Nagarik—in its writing, set design, and overall direction. Ray later wrote: “Some years later came Ajantrik. I attended the first screening. Watching it, I realized how far a true artist could go if given the opportunity.”

The gap between Nagarik and Ajantrik is about six years—a period in Ghatak’s life that was far from linear. These were the years of intense love, politics, marriage in 1955, and expulsion from the Communist Party. The shock was compounded in 1954–55 when his ideological differences with IPTA forced him to leave the group. One can understand why, for Ghatak, the step forward in cinema was almost proportional to a life-altering experience.

Let’s pause for a moment and look back at a remarkable chapter in Bengali cinema. The post-war, war-torn Europe produced its cinematic golden harvest by the mid-1940s, and within a decade, this new wave reached the hands of a small group of filmmakers in a famine-stricken, impoverished, third-world context. Alongside Ghatak’s centenary, even without a precise date, this entire new wave quietly reaches its estimated seventy-fifth year in 2025.

The 1950s and Bengali Cinema

In 1950, Bengali films included Kali Prasad Ghosh’s biopic Vidyasagar, Manu Sen’s literary adaptation Baikunther Will, and Naresh Mitra’s horror film Kankal. That same year, socially conscious cinema took a step forward with Premendra Mitra’s Kankantala Light Railway. In 1951, Satish Ghosh’s Anandamath, Ajay Kar’s Jighangsha, and notably Nimai Ghosh’s enduring Chinnamul appeared. By this time, the twenty-six-year-old Ghatak had already begun his direct engagement with cinema, acting on the big screen and contributing to film conceptualization.

While Chinnamul, often cited as the first socially conscious, socialist Bengali film, marks a key step in Ghatak’s cinematic work, he had earlier assisted in Manoj Bhattacharya’s Tothapi. This was under Bimal Roy’s supervision, who had written the script. As a conscious pioneer of Indian realism, it is worth remembering that Bimal Roy had made his first film Udayer Pathey (1944), followed by Do Bigha Zamin (1953). It was in this context, amid a series of other films, that Ghatak began his directorial journey in 1952, ushering in his own ‘new wave’ in Bengali cinema.

We also know that Italian neorealism had begun to merge with an Indian context in films like Chaitanya’s Neechanagore (1946), and earlier in Bimal Roy’s Udayer Pathey, consciously inspired by De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves. Motivated by social fractures, political passion, and the imperative to reach the people, Ghatak’s films emerge. In addition to his socially aware themes, Nagarik simultaneously advanced as an art film. Early work of cinematographer Ramananda Chattopadhyay and actor Satindra Bhattacharya show that Nagarik shared the neorealist trait of collaboration with emerging talents. Influenced by Brechtian theatre, the film thus represents the first step in a larger cultural shift.

Realism and Melodrama

Melodrama, as used in the West and long debated by critics, became a hallmark in Ghatak’s work. In early 1950s Bengali cinema, direct realism began merging with specific melodramatic structures, especially in Nagarik.

The term "melodrama," here, does not refer to exaggeration or overacting. Rather, it entails tales of everyday lives under capitalist alienation with often a central character or small family struggling through the darkness of everyday life. Realism is not inconsistent with melodrama; they work in concert with each other to create a narrative based on reality. Characters win or lose, experience grief, despair, love, and ultimate expression, yet the story never becomes absurd.

“Your path will change one day too, Raja!”

The narrative pace of Nagarik is slow, moving toward sudden shocks and darkness. A family from a large North Kolkata house relocates to a modest two-room apartment post-war and partition. The central male character, educated but unemployed, Ramu (Satindra Bhattacharya), is expected to find a job and restore the family’s stability. The father, now ill, played by Kali Banerjee, is principled but slightly rigid. Three women characters—the unemployed mother, the unmarried sister, and Ramu’s lover—each face their own struggles.

The cinematography emphasizes contrasts of light and shadow. Close-ups reveal half-lit faces, hinting at inner emotions. Youthful conversations carry subtle sarcasm and social helplessness. Even the smallest details—budgeting for two market trips, paying for a wedding, or participating in a political meeting—reflect daily struggles. The narrative progresses as the family moves slowly into a poorer neighborhood. And then, unexpectedly, a moment like the sound of “International” music injects a dramatic, almost hyper-local vibrancy into intimate family moments.

Wide-angle shots capture the urban landscape. Since Kolkata grows vertically rather than horizontally, these shots evoke contrasting emotions. The camera pans across the city, revealing the high-rise buildings trapping the smaller homes like a closed cage. Early dialogues convey a temporary discomfort, devoid of despair, gradually revealing characters’ helplessness. Neighboring figures, daily survival struggles, and minor tragedies quietly build tension. Political optimism and personal aspirations—of love, liberty, and dedication—intersect with social realities. The streets and the inner alleys become part of the story, where sedimentation plays the role of sociation, daily life, private circumstance, and shared experience.

In Ghatak's later films, and even in his first film, human vulnerability, ambiguity, and heartfelt sorrow loom large. Yet, the dialogues also allude to both youthful and Horatian satire, whether in the paternal-turned-filial conversation, or in the maternal-turned-filial conversation or in the street.

Nagarik’s dialogue-driven, theatrical style does not offer the pure cinematic delight of polished film. Moreover, the nearly lost positive print makes evaluating its cinematographic aesthetics difficult. Yet, inspired by Soviet montage and Ramesh Joshi’s editing, the narrative is delicately constructed from scene to scene. Ultimately, the film leaves an enduring question: “In the life of the citizen, which path lies at the other end?” Every century, we must seek our own answers. One recalls Bhaskar Chakraborty’s poignant lines:

"Ekhon shotabdi seshe chariidike bish, tobu/ benche thakbar moton nirjon sahos dekha dile/ dekha jaay shanto poth shanto din shanto bari shanto sondhyebela!"

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here.