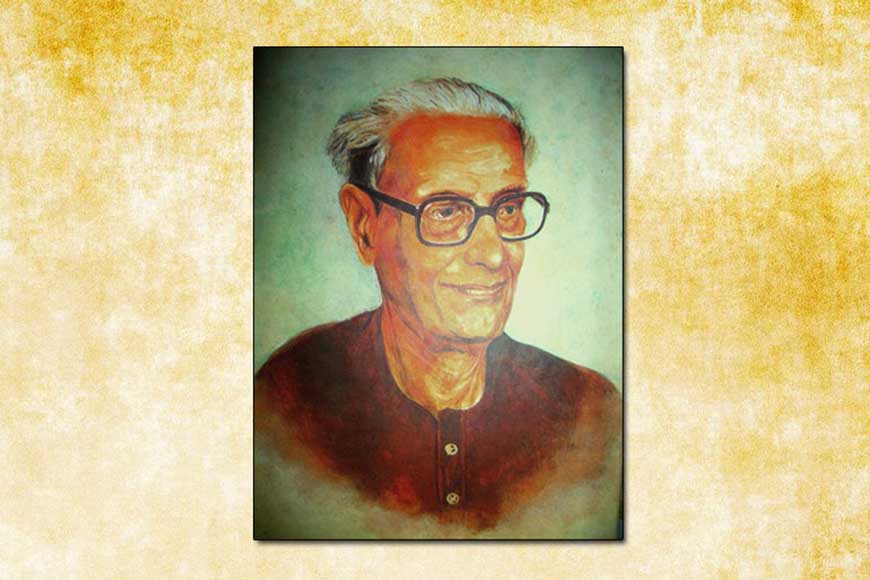

Why we need to remember Annadashankar Ray

‘I never write without reading, knowing, thinking. It takes time. Even with short pieces, I take time,” wrote Annadashankar Ray. In those short pieces, even those of a political nature, the focus was on expressing his core thoughts in as few words as possible. He knew that long, unnecessarily drawn out writing held little interest for readers. Depending on the content, most readers preferred sharp, refined, intelligent writing. Many of his political, social, even literary pieces often end in a page or a page-and-a-half. But they provide plenty of food for thought. Of course, he did produce long political essays too. Not all his short stories were really short, and he has several expansive novels to his credit.

He was the first to write an epic novel in Bengali, ‘Satyaasatya’, a work in six volumes, each with a different title. That was when he was still young. As a more mature author, he wrote ‘Krantodorshi’, in four volumes, on the partition of India and Bengal. Combining politics with love, social norms, communalism, humanism, and the history preceding Partition, the novel ends with the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi.

Prior to Partition, Annadashankar was an employee of the British-Indian government. As a member of the Indian Civil Service (ICS), he was a senior bureaucrat, trained in England.

He would make ‘points’ before starting to write anything, and then adding to or subtracting from these to produce the final piece, whether story, essay, poetry, even the rhymes he was famous for. Also, he would decide upon a title before he started writing, as though he wanted to convey the sum of his thoughts through the title itself.

Prior to Partition, Annadashankar was an employee of the British-Indian government. As a member of the Indian Civil Service (ICS), he was a senior bureaucrat, trained in England. As a government servant, his writings had to be necessarily guarded, and he couldn’t flout certain rules. So he chose a pen name: Lilamoy Ray, which he used to write numerous essays, largely socio-political, published in an India ruled by the British. They were all in Bengali, intended for a Bengali readership. Bengal, and Bangladesh, were in his blood, in his veins.

He could easily have chosen any other province to work in, once he returned to India as a trained ICS officer. Many of his contemporaries did make their aspirational ways to Bombay or Delhi. Rabindranath Tagore once asked him, ‘Why choose Bengal over other provinces of India?’ His prompt reply was: ‘I am devoted only to Bengal’. Whether the response pleased or displeased Tagore, ‘there was no change in his countenance’. For a moment, he once told me, ‘I wanted to say, with someone like you (Tagore) living in Bengal, why would I go anywhere else? But I didn’t say so, because he may have thought I was merely trying to flatter Gurudev.’

We know that Annadashankar spent most of his career in what was East Bengal, beginning with Chapai-Nawabganj in Rajshahi. It was here that his wife Leela learned Bengali from the professor and essayist of ‘Harmony’ fame, Muhammad Mansuruddin. Across several district courts of East Bengal, he spent years as a judge or district magistrate. A few months before Partition, he was posted in Mymensingh. And he wrote his much-read, much-beloved 25-line rhyme:

তেলের শিশি à¦à¦¾à¦™à¦² বলে

খà§à¦•à§à¦° পরে রাগ করো।

তোমরা যে সব বà§à§œà§‹ খোকা

à¦à¦¾à¦°à¦¤ à¦à§‡à¦™à§‡ à¦à¦¾à¦— করো!

তার বেলা?

(খà§à¦•à§ ও খোকা, ১৯৪à§)

A rough translation would read: ‘You are annoyed with your little girl/ because she broke a bottle of oil/ What about all you grown-ups/ Breaking India, dividing the soil?’ (Khuku o Khoka, 1947)

This immortal rhyme originated when the writer’s younger daughter Tripti, then all of two years old, dropped and broke a bottle of Jabakusum scented oil, which she was trying to fetch for her father. Annadashankar and Leela had five children, of whom three were born in East Bengal. Their son Chitrakam died in Chittagong when he was 10, and his memorial plaque stands at Kaivarta Dham even today.

Annadashankar’s friend circle was full of literary figures and intellectuals of Bangladesh.

Annadashankar’s friend circle was full of literary figures and intellectuals of Bangladesh. These weren’t just friends, but family, united by more than mere blood ties. It was he who suggested to Abul Fazal that the latter write his stories in the regional dialect of Chittagong. Annadashankar finds several mentions in Abul Fazal’s reminiscences. Had Partition not occurred, Annadashankar had every intention of settling in Shilaidaha, in Kushtia district, as he himself has written. One of his books, published from Dhaka, is titled ‘Amar Bhalobashar Desh’ (The Country I Love). This country was Bangladesh.

Born into a family of the Shakta (worshippers of Shakti) faith on March 15, 1904, Annadashankar spent his infancy and childhood in Dhenkanal, then a princely state of Odisha. His father was Nemaicharan Ray, and mother Hemnalini. Gradually, the family shifted from Shakta to Vaishnava philosophy, with all the latter’s attendant belief in the ultimate love for the divine that unites every living being. A faith in which religion is but secondary and religious strictures minimal, where humanism is above all. Something like the songs of Lalon Fakir, where his religion was immaterial. What was important was the connection with the divine, and love for all humanity. Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Christians - were all irrelevant. This irrelevance permeated every step of Annadashankar’s childhood. It was his Vaishnava sensibilities that perhaps drove him to write, ‘All this talk of caste, communities, it’s nothing. If we are true humans, then humanity comes first. Food has no caste. Sit at one table for a week, share your food, use common spoons, and the food will transform you, me, all of us, from Hindus and Muslims into family.’

Yet another of his similarly biting observations was, ‘In a communal clash, even if between Hindus and Muslims, it isn’t only people who die. Humanism, human senses die too.’ This is something I see happen around the world, including India. His writings contained predictions of what India would become, more like prophecies, and they are all coming true, every word. The more I observe, the more I realise how much of a clairvoyant he was, almost blessed with second sight.

Rathin Sengupta, the former chief secretary of West Bengal, once told me that a fully prepared RSS had decided upon a time and date to assassinate Annadashankar. When the plan was detected by the secret services, his house was cloaked in stringent security. Having observed all the activity, Annadashankar simply said, ‘Let them kill me, I’ll become a martyr.’ He called me to him and said, laughingly, ‘Being a martyr at my age is a thing of pride.’

Annadashankar belongs to both Bengals, splitting him is well nigh impossible.

While much of his sense of world humanism came to him from his family, some of it was of his own making. His wife, formerly Alice Virginia Orndorff of El Paso, Texas, became Leela Ray post-marriage. A Vaishnavite Hindu, married to a Protestant Christian, into whose family I, with my Muslim name, found a way. Living in the same house, eating at the same table, we were living examples of humanism. My family became his own. Relatives of mine from Dhaka who came to visit would stay in his house too. The same applied when he visited Dhaka, like family.

Annadashankar was a Bengali through and through, with no dilutions whatsoever, as his autobiography shows in detail. However, his first writings, specifically poetry, were in Odia. Indeed, he was one among five writers who have shaped modern Odia literature, and one of two Bengalis. Initially, he used the name ‘Sabujdal’ (inspired by Pramatha Chaudhuri’s ‘Sabujpatra’), though he himself credited Tagore as his primary inspiration.

Annadashankar’s place in modern Bengali literature and thinking is today beyond question, as luminaries like Sudhindranath and Buddhadev Basu have repeatedly testified. Many more like them have described Annadhashankar’s prose as an asset to Bengali literature. In the field of rhymes, he has been declared a ‘king’ by the poet Alokranjan Dasgupta.

His love for Bangladesh was born out of, and nurtured by, the very soil, the air, the natural landscapes, of the country. In 1971, writing about Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, he wrote:

যতদিন রবে পদà§à¦®à¦¾ যমà§à¦¨à¦¾

গৌরী মেঘনা বহমান

ততদিন রবে কীরà§à¦¤à¦¿ তোমার,

শেখ মà§à¦œà¦¿à¦¬à§à¦° রহমান

(অংশ ‘বঙà§à¦—বনà§à¦§à§’, ১৯à§à§§)

Another rough translation: ‘So long as the Padma, Jamuna/ Gouri and Meghna flow/ Mujibur Rahman, your legend/ Will continue to grow’. (Excerpt from ‘Bangabandhu’, 1971)

Annadashankar belongs to both Bengals, splitting him is well nigh impossible. In the context of India and Bangladesh, his birth anniversary becomes even more topical. As the days pass, he remains the second most commemorated icon in Bangladesh after Tagore. His birthday is merely an excuse to remind ourselves how deeply he permeates our thoughts, our senses, our political environs, our very beings. Bengalis remain indebted to him. This is not a debt that is easily repaid.

Translation: Yajnaseni Chakraborty