Calcutta Police trumped Scotland Yard with world's first fingerprint bureau

On August 16, 1897, Hridaynath Ghosh, manager of Kathalguri Tea Estate in what is now Jalpaiguri district in West Bengal, was found brutally murdered in his bungalow, his throat slit wide open. Topping the list of suspects was his former domestic help Ranjan Singh alias 'Kangali', who had just served a six-month prison term for theft. Thanks to bloody fingerprints found at the scene, police were able to link Kangali to the murder, the first time in the world that fingerprints had been used to detect a crime.

-and-Hem-Chandra-Bose.jpg) Azizul Haque (left) and Hem Chandra Bose

Azizul Haque (left) and Hem Chandra Bose

For those astonished by this revelation, it must also be said that in June 1897, the world's first official Fingerprints Bureau had been established in Calcutta, thanks largely to the efforts of three men - Sir Edward Richard Henry, Khan Bahadur Azizul Haque, and Rai Bahadur Hemchandra Bose. Today, the bureau is under the direct supervision of the Central Bureau of Investigation.

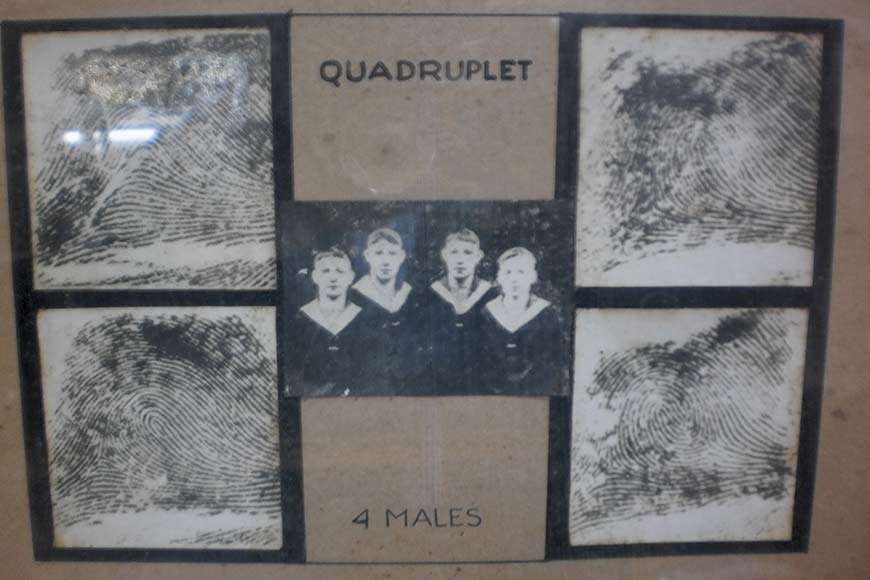

Working in England in 1890, Sir Francis Galton had been able to conclusively prove that no two people had the same fingerprints, and that these prints, once collected, would be permanent, thus establishing fingerprinting as a science.

Explaining how the prints had been used to convict Kangali, Henry, who went on to become London's Commissioner of Police, later told the Belper Committee: "What is that case? Shortly, it was that a man was found in a teagarden with his throat cut. It was some distance from the nearest police station, and the police could get no clue. The police suspected, among others, an ex-servant of the man, who had been imprisoned for theft. I was inspecting up the line, and on asking the police officer if he had any clue, he produced among other things the little book you see here, with two brown marks on it. As soon as I saw that I was able to make out that the marks were probably caused by one of the digits of the right hand..."

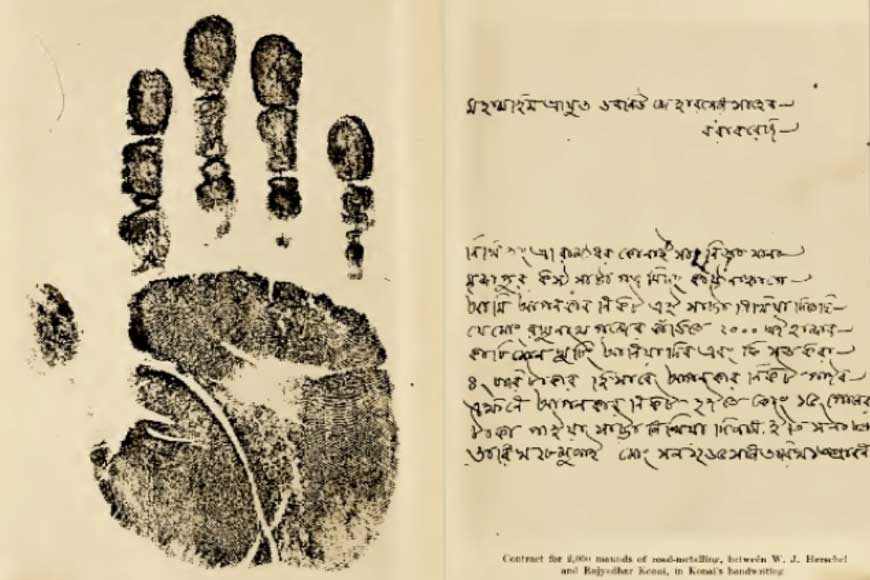

It must also be said that even Scotland Yard had to wait until 1901 to get its own Fingerprint Bureau, and the reason that Calcutta, then the capital of British India, got there first was the pioneering work done not just by Henry, but also by Sir William James Herschel, one-time Collector of Hooghly, who extensively, though informally, used fingerprints for official purposes between 1858 and 1880. A few readers will probably recall how Herschel's name found its way into popular Bengali culture through Satyajit Ray's 'Sonar Kella' (1974), where Sidhu Jyatha asks Feluda, "Who was William James Herschel?"

Working in England in 1890, Sir Francis Galton had been able to conclusively prove that no two people had the same fingerprints, and that these prints, once collected, would be permanent, thus establishing fingerprinting as a science. Together with Henry and Herschel, Galton formed a trio who pretty much pioneered the fingerprinting techniques still used the world over.

Also read : When a cigarette butt helped nail a murderer

Back in India in 1891, Henry was Inspector General of Bengal Police when he began a series of experiments intended to classify various kinds of fingerprints. Based on these experiments, two officers of the Anthropometric Bureau, Hemchandra Bose and Azizul Haque, worked out a mathematical approach for the classification of fingerprints. In March of 1897, a government committee approved the use of fingerprints to identify criminals, which in turn led to the setting up of the Fingerprints Bureau in Calcutta that same year.

Which brings us back to the Kathalguri murder, where the killer was identified through fingerprints. However, on May 25, 1898, Ranjan Singh alias Kangali was acquitted by a court owing to the fact that existing Indian laws did not have a provision for fingerprint evidence. Clearly, an upgrade was required, and in 1899, the Indian Legislature passed an amendment which allowed the laws to be changed to accommodate fingerprint evidence.

No two fingerprints are same

No two fingerprints are same

Hemchandra Bose, who had joined the Bengal Police Service as a sub-inspector in 1889, and Azizul Haque, a mathematics prodigy who was a student at Presidency College when Henry recruited him as a sub-inspector, were both personally supervised by Henry. Unbeknownst to them, they were to become part of world history when they helped Henry formalise and formulate his experiments.

Back in India in 1891, Henry was Inspector General of Bengal Police when he began a series of experiments intended to classify various kinds of fingerprints. Based on these experiments, two officers of the Anthropometric Bureau, Hemchandra Bose and Azizul Haque, worked out a mathematical approach for the classification of fingerprints.

Bose's grandson Amiya Bhusan Bose joined the West Bengal Police Service as part of the 1952 WBCS batch, and retired as DIG of West Bengal Police in 1988.

Despite their great success in classifying fingerprints, however, more than one Indian historian has suggested that Bose and Haque were never adequately acknowledged for the tremendous impact that their work had. In their book 'Indian Civilization and the Science of Fingerprinting', G.S. Sodhi and Jasjeet Kaur suggest that Henry's System of Fingerprint Classification be renamed the Henry-Haque-Bose System of Fingerprint Classification. Though this suggestion has not materialised , the UK Fingerprint Society has recently instituted a research award in the names of Haque and Bose. Perhaps a few decades too late, but these two pioneering policemen from Bengal may finally be getting their due.

Information inputs courtesy: Niharendu Roy, ACP (retd), Kolkata Police