Did you know Kolkata had a thriving Opera culture once upon a time?

Kolkata has always been the Mecca of Bengali culture that celebrates theatre. So did British India. It had a culture that still fascinates artists, historians and writers across the world. Since 1694, the port city of Calcutta, had British East India Company (EIC) exporting materials such as silk, opium and indigo and importing Opera. In 1775, Calcutta boasted of its first European theatre (the Calcutta Theatre). There were 132 performances. They were rare but mostly amateur. In eighteenth century, Calcutta theatre culture fell out of operation.

In 1813, when the relaxed migratory framework was first trialed, Calcutta’s first theatre was built. It was called Chowringhee Theatre, a professional European group. ‘Calcutta’s changing economy and demographic is no mere coincidence, for it was the changing attitude to empire, and the consequent shifts in politics and society that made the theatre a viable business venture for the first time in Calcutta,’ said Esmeralda Monique Antonia Rocha in her thesis Imperial Opera: The nexus between opera and imperialism in Victorian Calcutta and Melbourne, 1833–1901.

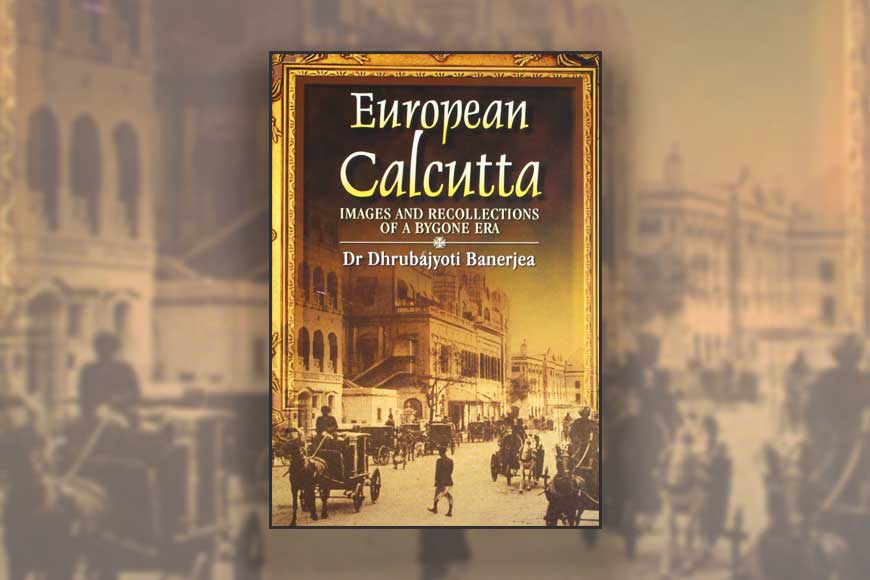

Chowringhee Theater in Calcutta became a hub of social activity ‘for Calcutta’s elite would gather here every evening for gossip and drinks, whether there was a performance on the bills or not,’ according to Dr Dhrubajyoti Banerjea, author of European Calcutta , Images and Recollections of A Bygone Era. In next twenty years, the Chowringhee Theatre presented dramatic plays with music.

In 1820s, the theatre also had a modest orchestra which included professional musicians from a band. The band consisted of a handful of violinists, one double bass, two cello, two bassoons, two flutes, two clarinets, two horns, two trumpets and a set of timpani. The orchestra was certainly kept busy: each year over Rs. 500 worth of sheet music was imported from England. Frenchman Delmar was the head of orchestra. It was music for the theatre's dramatic performances, which included many Shakespearean plays only. The band also performed in between acts, and supported the occasional soloists who ventured to Calcutta, such as the German violinist Scheitelberger. One of the most prestigious musicians to come to Calcutta was Danish pianist David Gottfried Matrin Kuhlau (the brother of composer Friedrich Kuhlau). He stayed back in Calcutta as a respected teacher and music director.

By 1828, Calcutta had dozen more professional orchestral musicians. There were also nine professional non-orchestral musicians Calcutta and two musical instrument repairers & makers in Bengal. According to British journal The Harmonicon, in 1823, the presence of several professional singers in Calcutta were mentioned. They were Mr. Wilson (who was also the lessee of the Chowringhee Theater), Mr and Mrs Bianchi-Lacy, Mrs Cooke, Mrs Kelly and Miss Williams. The Bianchi-Lacys were favorites of the court at Windsor Palace and quite accomplished singers. Jane Bianchi- Lacy (née Jackson 1776–1858) was a soprano who had appeared at the Concert of Ancient Music in 1798. After marrying Italian composer Francesco Bianchi, she performed at the King’s Theater, where she was at first thought to be a pleasing performer despite her inferior voice. By 1815, she had made vocal improvements and some even judged her to be ‘one of the finest Handelian singers of her day’. In 1818, Jane Bianchi-Lacy arrived with her husband John Lacy in Calcutta for eight years.

In 1830s, the first Italian troupe came and performed Verdi’s I Lombardi and Il Trovatore. The next two concerts attempted a more authentic operatic experience, by presenting whole operas in concert form. The first was Ernani, a Calcutta première, and the second was Rossini’s evergreen opera Buffa, Il Barbiere di Siviglia.

In 1839, the Chowringhee Theatre was burnt to the ground. Calcutta lost its only temple of art. The damage to the building and assets amounted to Rs. 76,000 in those days. Calcutta’s theatrical fraternity took a big hit with departure of many singers and actors. The three first opera troupes left. Calcutta’s star actress and sometime opera singer, Esther Leach took ill in England. Mrs Goodall Atkinson, Calcutta’s theatrical and operatic mainstays, died shortly after the fiery destruction of the Chowringhee Theatre.

However, by 1873 the opera culture in Calcutta took a different form. Work such as Sati ki Kalankini, mixed traditional Bengali music- theatrical traditions (such as the yatra) with Western music-theatrical influences came into existence. Amongst the Western influences were a greater employment of mechanic scenes and sets, the use of a conductor and a larger band, the idea of the genre being a high-art, rather than popular, music-theater genre. Great National Opera was supported by Calcutta’s Bengali babu class extensively. Other supporters were Maharajah of Vizianagram and the Maharajah of Jodhpur. They were generous benefactors and patrons of the city’s Italian Opera and Town Band.

Opera no longer remained a part of the White settlements only. It provided broader base of patronage for the art form and secure opera’s future. Colonel Wyndham’s had positive influence on Calcutta’s operatic culture when he benevolently extended to native Bengalis. In 1875, Wyndham came up with a plan to rescue Italian Opera from its precarious financial position leasing the Lindsay Street Opera House to the Great National Opera towards the end of the Italian Opera season. The Great National Opera (GNO) was just one of many cultural activities that came to be collectively known as the Bengali Renaissance, a socio-cultural phenomenon with nationalist-political overtones. Established by illustrious Bengali artists as the singer/ actor/author Nagendranath Banerjee in the winter of 1874–75,393 the GNO (like its sister movement, the Great National Theater which had been established in 1873) had two aims.

Firstly, to provide public performances of newly-composed Bengali music- theatre works. This would expose Bengali art to a much wider audience than was previously the case, for traditionally such performances had been presented at the private residences of Calcutta’s Indian elites. Secondly, these public performances would invigorate Bengal’s cultural pride and fan the flame of nationalist sentiment that was then simmering throughout the highly-striated Bengali community.