Gobindaram, the nationalist who preceded Indian nationalism

June 16, 1756. The day Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah of Murshidabad launched his brief but devastating siege against the ‘British settlement’ of Calcutta. Three days later, he had control over the township. How the British shook him off and eventually wrested not only Calcutta, but the whole of Bengal from him at the Battle of Plassey is one of history’s case studies. But what interests us here is that before Plassey, Robert Clive and nawab-to-be Mir Jafar had entered into a secret agreement stipulating that Mir Jafar would pay damages worth Rs 20 lakh to some of Calcutta’s local luminaries, the rich Bengalis who partnered the East India Company’s operations, for setbacks suffered during Siraj’s siege.

Naturally, Clive’s secret pact did not remain secret, and as soon as the siege had lifted, some of the city’s wealthiest men were knocking on the company’s doors, demanding restitution for damages suffered. Eventually, a Restitution Commission was formed to disburse such compensation as the company deemed fit (Clive being Clive, he apparently kept half the amount for himself), and approximately Rs 10.15 lakh was handed out to a few select recipients.

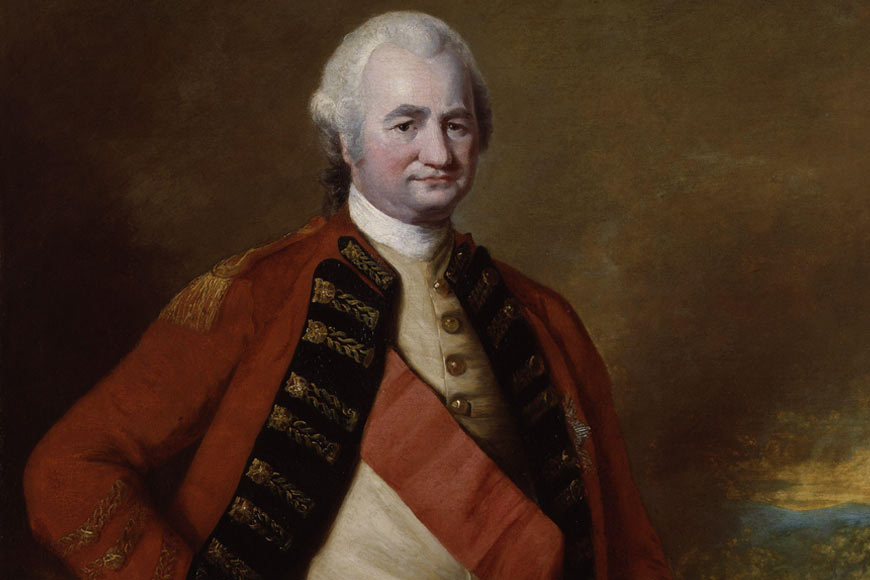

Robert Clive

Robert Clive

Guess who took home the lion’s share? The infamous ‘Black Zamindar’ Gobindaram Mitra, despite having suffered virtually no damage during the attack. The hero of our story today, Gobindaram and his son Raghunath claimed an amount of Rs 4,12,280 from the British, eventually going home with Rs 3,75,000. None of the other recipients managed to wangle that high a sum from the miserly British, and wonder of wonders, Gobindaram wrested a further Rs 25,000 for 12 of his dependents, including his three mistresses Ratan, Lalita, and Hartan Bibi, and even his ‘coolie’ Kuroram Biswas! As a bit of fun trivia, some of these so-called dependents were later found to have been dead for several years.

So who was this man, who could apparently make the ‘sahibs’ dance to his tune? Some British officials, among them collector John Zephaniah Holwell of ‘Black Hole’ fame, saw him as the devil incarnate, a cruel, arrogant, corrupt fortune hunter who had defrauded ‘John Company’ of several lakhs of rupees. Others were on excellent terms with him, regularly eating and drinking their fill at his lavish parties, and protecting his interests from fellow Englishmen. For the native inhabitants of Calcutta, Gobindaram was nothing short of a legend, who dared take on the already mighty British on the strength of his money, influence, and a well paid private army.

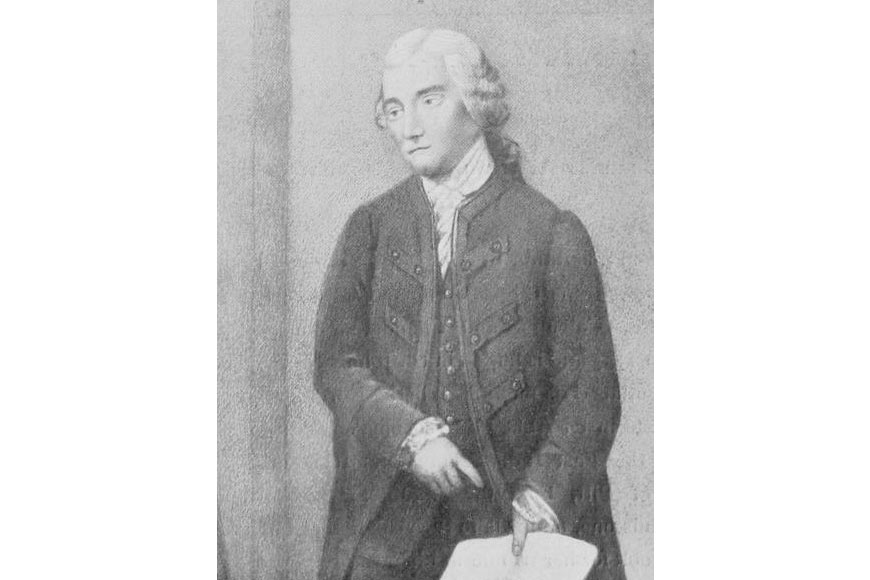

John Zephaniah Holwell

John Zephaniah Holwell

A resident of Kumortuli, Gobindaram originally belonged to Chanak or Barrackpore, the two names seemingly used interchangeably until the 15th century. His family moved to Gobindapur at some point, but it isn’t clear if this was before or after Gobindaram’s birth. A sketchy account of his life published in 1869 by ‘A Member of the Family’ claims that Gobindaram died in 1766 at the age of 80, which would make 1686 his birth year. However, there is little reliable information to show how he entered the service of the company, though it does appear that he began his career as a salaried employee in 1722, and spoke Persian and English quite fluently. His eventual role would be that of deputy to the collector, a position which gave him the right to collect various taxes and duties from the locals, as well as maintain law and order in a rapidly growing city.

By 1730, he had amassed enough wealth to erect one of the architectural marvels of contemporary Calcutta, a Shiva temple known as the Black Pagoda, whose spire rose to a height of nearly 140 feet. Tragically, the structure was virtually destroyed by the horrific cyclone of 1737.

What was the source of Gobindaram’s massive wealth? A mere salary was not enough, surely. His detractors, with his boss Holwell leading the pack, claimed he was routinely embezzling company funds. When Holwell demanded of Gobindaram that he explain his accounts, the latter simply reminded him that they were both company employees and hence equals, which meant Gobindaram was not answerable to Holwell in any way. That must have taken some nerve.

When Holwell took his complaints to the Calcutta Council and the latter asked to see Gobindaram’s accounts, he led them on a protracted dance, first claiming his ledgers had been destroyed in the 1737 cyclone, and then that termites had eaten them up. Eventually, thanks to his many ‘friends’ in the council, he got away with a penalty of a mere Rs 3,397, small change for a man of his means.

The determined Holwell even arranged to have Gobindaram sacked on charges of indulging in ‘private trade’ in textiles and lime, supposedly illegal for salaried company employees, yet something that every employee from governor to writer (clerk) routinely engaged in. Horrified by Holwell’s order, however, the council hurriedly restored Gobindaram to his post. This, after Gobindaram had defiantly declared that yes, he did engage in private trade as did everyone else, because the company did not pay him enough to maintain his high-profile lifestyle.

There are many more examples of his characteristic boldness. During the great Calcutta famine of 1752, he submitted a report to council president Roger Drake, clearly stating that in 1751, the price of foodgrains had been the highest in the past 60 years. “Many of your inhabitants have perished within the town with hunger,” he wrote. And then came a line that ought to be immortal: “If cloth is dear, a poor man may put off the buying of a new coat until the price falls; but for victuals, when hunger presses, everyone must buy if he has money to purchase it.” He also included a clear reference to how the company’s coffers had benefited from an increase in sales tax.

Thus spoke ‘Gobindaram Mitter’. The man who ruled Calcutta with an iron fist in the 18th century, and whose legend has sadly not been documented for us to enjoy. But we can say this much: long before Indians even thought of a freedom struggle, Gobindaram was taking the fight to the British in ways that they couldn’t counter.