Tables turned: how an Indian bought the East India Company

'The merchant's yardstick, which, at dawn break/ Appeared as the royal sceptre...'

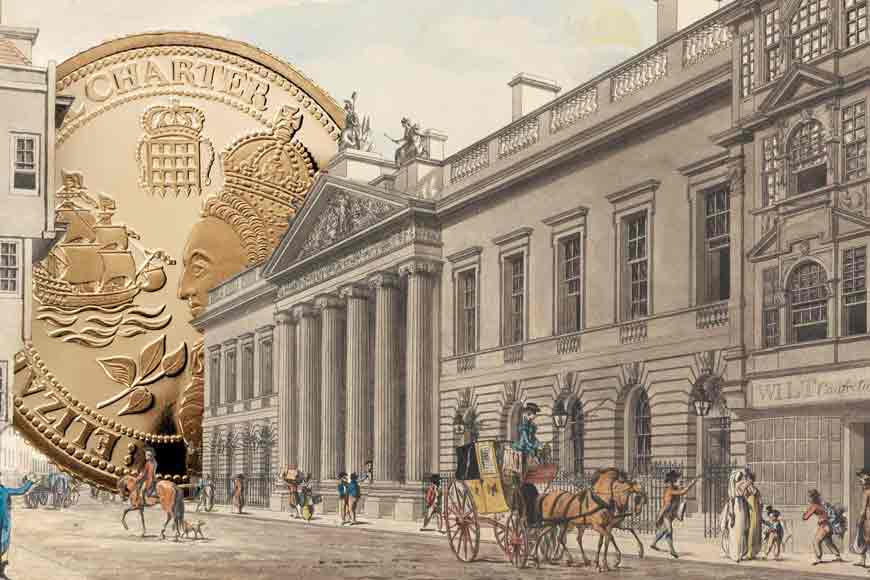

This rough translation of Rabindranath Tagore's words nonetheless perfectly explains the changing nature of the British presence in the Indian subcontinent. And the epicentre of this change was a single entity - the British East India Company. A behemoth born in the year 1600, one which swallowed everything in its quest to become a global brand on the strength of its Indian enterprise. Between 1619 and 1690, it had set up trading posts in Surat, Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta, in that order. In fact, by 1647, the company had 23 factories in India, and subsequently, Fort William in Calcutta, Fort St George in Madras, and Bombay Castle became its most prominent factories.

But how the company first appeared on Indian shores, and in the Mughal court, as a trading body, and how it gradually took over India's political establishment and became an instrument of colonisation, is a lesson well-entrenched in history. What is less well known is, what actually happened to the British East India Company once it was dissolved after the Mutiny of 1857, when the British crown took direct administrative control of the subcontinent.

Well, the wheel has turned full circle.

Over many generations, as the once mighty 'Company bahadur' became a distant memory, relegated to the pages of history, most Indians forgot about it. But one Indian didn't.

His name was Sanjiv Mehta, an immigrant entrepreneur who moved to the UK from Mumbai in the 1980s. Almost exactly a decade ago, on August 14, 2010, Mehta relaunched the East India Company as a luxury food store in London. That single store has by now spawned quite a few more.

The irony of an Indian taking over an establishment which once participated in the enslavement of his country is so rich that it beggars description. As Mehta made it a point to remind BBC at the time, "the project was not simply a commercial venture - there was an emotional connection too". What's more, Mehta ensured that the date of the relaunch coincided with the day the British East India Company was finally and officially dissolved, in 1874.

The dissolution was not the end, though. A vestigial entity survived, and continued to trade in commodities such as tea and coffee. Though a far cry from the days when it ran a parallel administration in India with its own officials and armed forces, its survival at least kept hopes of a revival alive, and a 400-year-old chain unbroken. That said revival would be staged by an Indian was merely the kind of delicate touch that only destiny can pull off.

Today, the East India Company is an upmarket consumer brand focused on "luxury foodstuffs", much as it was at the height of its powers, when the principal commodities were cotton, silk, indigo, salt, spices, saltpetre, tea, and opium. At that juncture, it was one of Britain's biggest employers, not to mention revenue earners. That is obviously no longer the case, but how deep the wounds inflicted by history can run was evidenced in the thousands of emails that Mehta received once news of his venture went public. Not just from Indians in India, but from the Indian diaspora in countries such as Fiji and Barbados, where their ancestors had been sent by the Company as plantation workers, wrenched from a homeland they never saw again.

There were other East India companies in India, belonging to other European powers such as the Dutch and the French. However, none of them came remotely close to the British in terms of political influence or financial might. In that sense, however perverse the reasoning, the British East India Company displayed rare depth of vision and unmatched dynamism.

With the 'new' East India Company, Mehta had dreams of returning to the Indian market. Will that reopen old wounds? The answer is as yet unknown, but the potential seems enormous. The East India Company still sells tea, chocolates and condiments from many parts of the world. It still employs a British workforce, and has made cautious inroads into such overseas markets as Dubai, recalling the East India Company's 'Persian Gulf Residencies' of yore.

Notwithstanding the commercial success of the venture, that a brand synonymous with the subjugation of India has changed colour so completely is possibly a bigger success story from the Indian perspective. Today, we can celebrate its every achievement as a bona fide 'Indian' one. The pain and anguish once associated with the name can now truly be relegated to the archives.