New documentary pays tribute to the dhaak, the soul of Durga Puja

A hollowed mango tree log about 2.5 to 3 feet long, covered at both ends with goatskin (now replaced by fibre or other synthetic materials) - that is a ‘dhaak’, the quintessential Bengali percussion instrument, inextricably associated with Durga Puja.

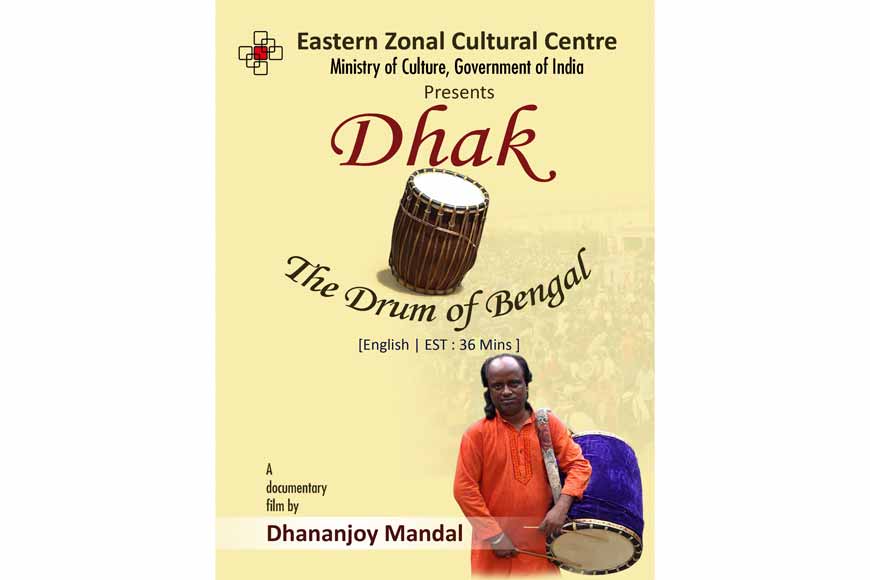

One of many indigenous musical instruments under threat in modern times, the dhaak and its dhaakis (drummers) are the subject of a documentary by 37-year-old National Award-winning filmmaker Dhananjay Mandal, titled ‘Dhak - The Drum of Bengal’, scheduled for screening at the Kolkata International Film Festival later this year.

Dhananjay Mandal

Dhananjay Mandal

Notwithstanding the fact that the dhaak and Durga Puja have become almost interchangeable, the drums actually begin beating at Gajan, the Hindu festival celebrated mostly in rural Bengal involving such deities as Shiva, Neel and Dharmaraj, starting at the beginning of April and lasting roughly a fortnight. The beats reach a peak during Durga Puja, but don’t end there. Hutom Pyanchar Naksha (Sketches of Hutom the Owl) by Kali Prasanna Singha, a seminal 19th century satire in Bengali, documents the presence of dhaakis in urban Kolkata during the Gajan and Charak festivals.

Mandal has travelled the length and breadth of West Bengal, going into villages where dhaakis eke out a livelihood, generally amidst abject poverty. The film explores the lives of the dhaakis and their insight into the art of playing the dhaak, which is gradually dying a slow death.

One expert dhaaki says the dhaak belongs to prehistoric times, as it was found in Egypt and China around 4000 B.C., during the bronze age in Vietnam and around 2500 years ago in Sri Lanka. He adds that the name ‘dhaak’ is derived from the word ‘dhaaka’, which means covered on both sides. The drum is played with a pair of sticks at one end, while the other end, known as the ‘banyaan’, is left untouched. The entire film is enriched by the wonderful and lucid commentary by the late Jagannath Guha. The language is fluid and flowing with good descriptive details any non-Bengali can easily follow.

The dhaakis are generally very poor and when the festival seasons are off, they take on jobs as wage labourers in other people’s farms, or drive auto rickshaws and totos, or repair bicycles, or engage in cane work or even as cobblers.

Dhaakis prepare or restructure their instruments or acquire new ones for the major festival season during the monsoon so that they are prepared fully with their dhaaks. The film also covers Kolkata, where Puja organisers gift dhaakis with bright costumes to add more colour to the festival and the film.

Today, dhaakis live in almost every district of West Bengal. Their largest concentration is in Murshidabad, followed by Birbhum, Malda, Burdwan, East and West Medinipur, Bankura and Purulia. A smaller number live in northern and southern Dinajpur. Most of the dhaakis who migrated after Partition live in both northern and southern 24 Parganas. Their playing style belongs distinctly to traditions from across the border. Dhaak players also lived in Kolkata in the past, and the urban settlements of Dhakuria and Kasba were home to them.

Mandal sheds light on some traditional dhaakis who have switched to other occupations for survival and security but they say that their passion for the dhak is still alive and vibrant. There are a few dhaakis who make a comfortable living right through the year. Among them are Jiten Dhaki from Ketugram village in Bardhaman, Hanriram Kalindi from Balarampur in Purulia who claim that with private pujas right through the year, when the dhaak is much in demand, there is no dearth of calls for dhaak performances even in the off-season.

Different rhythm compositions are used for different occasions even during Durga Puja – one when the Goddess is being taken to the mandap, one when she is welcomed, one when she is being worshipped, varying during the puja from morning to night.

The most famous among the dhaakis is Gokul Das, who has earned the sobriquet of ‘Emperor of the Dhaak’. His fame has spread far beyond his home of Maslandapur in 24 Parganas to the rest of the country and the world. He travels throughout the world now, as a performer, and even rides his own car. He says that dhaakis are in demand for extra-religious functions also, such as when the PM is coming for a visit or a foreign dignitary wants to be introduced to folk performances. But one old dhaaki whose son and grandson are following in his footsteps laments that dhaakis are not given the respect they deserve as folk artists.

Also read : After Pather Panchali, there is Talnabami

This may be partly due to there being no written course or institute to train dhaakis anywhere in West Bengal. The smaller boys learn through observation when they play on the kanshor (a circular metal plate beaten with a stick) as an accompanying instrument from their boyhood, and grow up to become dhaakis in their own right. “Today there are only a few dhaakis who can perform all the rhythmic patterns to perfection,” says Gokul Das. Some children who have now been educated refuse to follow the family occupation.

Another dhaaki maintains that with the spread of digital entertainment, copies of dhaak performances are now being played in Pujas from compact discs and hard drives. The dhaakis may be losing out on customers, but the popularity of their music continues to grow.

So, Gokul Das has taken the initiative to write down the rhythm and beat notations which others may follow while learning to play the dhaak. The problem is that most youngsters from dhaaki families are not educated and come into the profession almost organically, so they do not even realise the need for training.

Das has also introduced women into this male-exclusive folk form of art. “I began with 15 women and now I have 70 women dhakis in my team while many women have formed their own bands. I found a lady in the US playing instruments in a shop where I had gone to buy a saxophone. I asked myself – if this lady can play on musical instruments, why can’t our women be introduced to the dhak?” The film then cuts to a group of colorfully dressed women of different ages standing in a semi-circle to learn from Gokul Das. So, this is no longer a male-exclusive profession.

Just as calypso beats are unique to the West Indies, the sound of bagpipes makes one imagine Scotland, so does the sound of the dhaak paint a picture of Bengal. This film is dedicated to the fledgling breed of dhaakis without whom autumn in Bengal is never complete. The film is not pessimistic or dark because it is brightened with the smiling faces of the dhaakis who do not wear their sad stories on their faces and play on, when it is festival season. ‘Dhak – The Drum of Bengal’ ends on a note of hope and optimism.