The citizen heritage keepers of Kolkata

Johan Joseph Zoffany was a famed German painter, whose clients included several members of the Austrian and British royal families, and who was declared a baron by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria in 1776. But Johan Joseph Zoffany is also the man who will forever be linked to Kolkata’s past, and its heritage. Because it was he who created what has become one of the city’s most valuable works of art, ‘The Last Supper’ (1787), which hangs in St John’s Church, near BBD Bag. On a tour of India from 1783 to 1789, Zoffany also painted, among other things, portraits of Warren Hastings, then Governor-General of Bengal, and the Nawab Wazir of Oudh, Asaf-ud-Daula

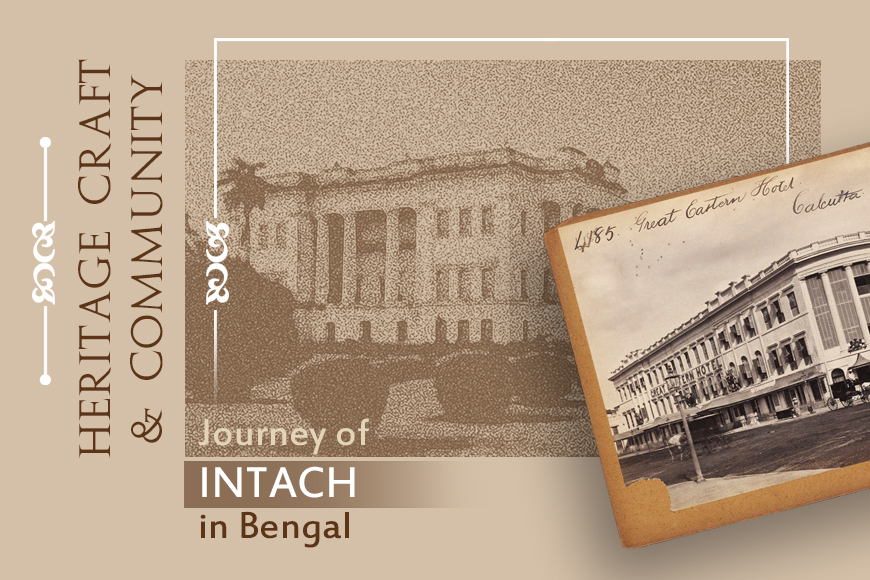

Why have we started a story on the Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage (INTACH) with Zoffany? Because in 2010, INTACH, in partnership with Goethe Institut, became the driving force behind the restoration of ‘The Last Supper’ to its original splendour, which is how a modern visitor to St John’s Church sees it. Today, INTACH is also one of the very few organisations in the city which works to restore and conserve any work of art, big or small, in an effort to preserve the city’s cultural heritage.

Why have we started a story on the Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage (INTACH) with Zoffany? Because in 2010, INTACH, in partnership with Goethe Institut, became the driving force behind the restoration of ‘The Last Supper’ to its original splendour, which is how a modern visitor to St John’s Church sees it. Today, INTACH is also one of the very few organisations in the city which works to restore and conserve any work of art, big or small, in an effort to preserve the city’s cultural heritage.

Back in 1984, a full-page advertisement appeared in leading national dailies with the headline: ‘Wanted: an army of conscience-keepers’, to ‘protect what is rightfully theirs’. The name of the advertiser was Rajiv Gandhi. The new Prime Minister was also the chairman of INTACH nationwide. Sitting in Kolkata, a young mechanical engineer and IIM post-graduate named Gour Mohan Kapur noticed the advertisement, and the powerful call to action appealed to his senses. “I had no formal training in history, heritage conversation or restoration, but all around me, I could see how Kolkata was losing built heritage like the Gwalior Monument, or Prinsep Ghat, or the entire riverfront,” he says. “These were landmarks which were dear to me.”

After restoration

After restoration

At about the time the advertisement was published, a water body close to Kapur’s home in Hastings was about to be filled up. And one of the first things he did after signing up for INTACH was to try and take steps to prevent it, which he successfully did, aided by public participation. What made the achievement unique was that INTACH is entirely a voluntary citizens’ initiative to preserve India’s heritage and culture, and counts among its members people from literally every walk of life.

Beginning with Kapur and a handful of like-minded individuals, INTACH’s Kolkata chapter today has several achievements to its credit, such as the restoration of Zoffany’s work. “Our outlook is national, but we are also extremely invested in local heritage,” says Kapur. The Gwalior Monument and Prinsep Memorial would be cases in point.

Beginning with Kapur and a handful of like-minded individuals, INTACH’s Kolkata chapter today has several achievements to its credit, such as the restoration of Zoffany’s work. “Our outlook is national, but we are also extremely invested in local heritage,” says Kapur. The Gwalior Monument and Prinsep Memorial would be cases in point. Once in shambles, both were restored once Kapur, through INTACH, began writing and campaigning about them. Among INTACH Kolkata’s earliest initiatives was to create a list of built heritage structures in the city.

Today, Kapur’s home houses the INTACH Restoration Centre, set up in 2005, where senior restorer Subash Chandra Baral, and restorers Arindam Debnath and Debabrata Singha are at work daily, piecing together invaluable pieces of Kolkata’s heritage. Speak to them, and they will enthusiastically describe the processes of both conservation and restoration, and proudly show you the albums they have created of their work.

Debnath laughingly recalls the time when they were working on restoring an ancient Buddhist scroll belonging to the Yolmowa Mag Dhog Monastery in Aloobari near Darjeeling. “The only other copy is in a monastery in Tibet, and the scroll is so holy that visitors are not even allowed to see it. When we were working on it, people from the monastery would actually come and bow before us, because we were restoring something so holy!”

Such successes have come consistently. On its website, INTACH Kolkata says, “The centre has taken special care and conservation work of the objects related to Netaji Subhash Bose in Netaji Museum, Netaji Bhavan, Kolkata and the conservation work of the objects related to Sir J.C. Bose and his family members of the residential house of Sir J.C. Bose, the father of Modern Physics, is going to be converted into Science Heritage Museum.”

Also memorable, says Kapur, was the ‘Europe on the Ganges’ river cruise, a project close to their hearts, and the project began in 1993 with documentation of “Euro-Indian urbanism” along the banks of the Ganges. The cruise is a crucial reminder of how several European nations had built settlements in Bengal long before the British arrived. “Our documentation led us to create a heritage tourism corridor along the river,” says Kapur. “We felt it was a great idea to attract tourists, both local and from outside. Over the years, the project came to fruition, and it was very satisfying to lay the foundation for something that others could build upon.” Likewise, INTACH was also involved in the restoration of the Danish heritage of Serampore or Srirampur in Hooghly.

Heritage Keepers of Kolkata

Heritage Keepers of Kolkata

Today, INTACH Kolkata boasts roughly 150 members, including those with the technical expertise needed for restoration and conservation. Increasingly, there is an effort to involve schoolchildren and their teachers across Bengal in these efforts, though Kapur does agree that the ‘mass mobilisation’ to ensure the power and influence required to protect the city’s cultural and architectural heritage is still some way away. “We would have loved to open chapters in every district. There are plenty of enthusiasts, but the passion needs to be channelised and focused,” he says.

Beginning with Kapur and a handful of like-minded individuals, INTACH’s Kolkata chapter today has several achievements to its credit, such as the restoration of Zoffany’s work. “Our outlook is national, but we are also extremely invested in local heritage,” says Kapur. The Gwalior Monument and Prinsep Memorial would be cases in point.

INTACH Kolkata is also credited with the publication of several beautifully designed and seminal books covering the history and heritage of several districts of Bengal, though many of these books have perhaps not received the audience they deserved. “Heritage can be a revenue earner, too,” says Kapur. “Heritage tourism is a huge source of income in Europe, for example. But now, with heritage walks and other such initiatives coming up, we hope more people will see the economic potential.” What he takes pride in is the fact that INTACH was a precursor to much of the heritage conservation work now afoot.

On the anvil is a project to restore and conserve the homes of 10 eminent Kolkatans - Satyen Bose, Meghnad Saha, Pankaj Mullick, Tarashankar Bandopadhyay, Mrinal Sen, Uttam Kumar, V. Balsara, Jamini Roy, Ali Akbar Khan, and Chuni Goswami – to begin with, and work has already begun to that end. As Kapur displays the dazzling steel-grey plaque to be erected at Pankaj Mullick’s home, one hopes for the city’s sake that he and INTACH Kolkata receive the mass support they so urgently need.