The feminine divine that breathes through Bengal – GetBengal story

Faith doesn't simply exist in temples in Bengal; it also moves through forests, rivers, and red earth. The divine feminine is not an abstract idea here; it is something that exists. Her breath lingers in the air, fierce and tender, eternal. This region is the land of the Shaktipeeths—sacred places where, it is believed, the body of Goddess Sati fell, giving birth to the geography of Shakti itself.

The story begins with Sati, the daughter of King Daksha and consort of Lord Shiva. When Daksha insulted Shiva, Sati immolated herself in grief. Stricken with sorrow, Shiva roamed the cosmos carrying her lifeless body. To end his anguish, Lord Vishnu’s Sudarshan Chakra cut the body into pieces, scattering them across the Indian subcontinent.

Each place where a part of her body fell became a Shaktipeeth, a seat of divine feminine energy.

Of these fifty-one sacred sites, Bengal cradles some of the most powerful shaktipeeths. They form a living circuit of devotion — a trail that binds myth and memory, past and present, land and soul.

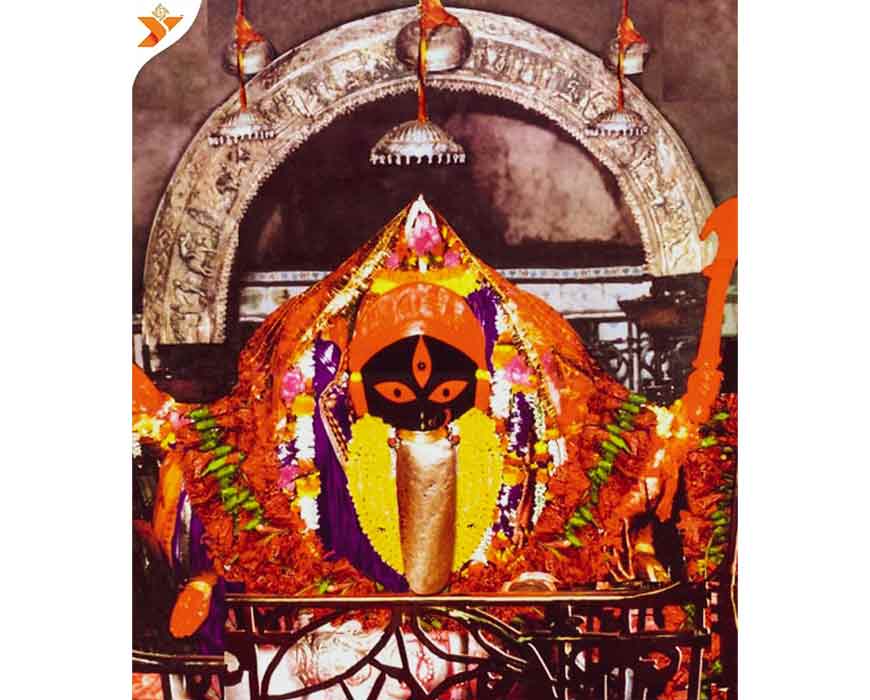

Kalighat

Kalighat

Kalighat in Kolkata is perhaps the most famous of Bengal’s Shaktipeeths. It is said that the toes of Sati’s right foot fell here. Here, the Goddess is both fearsome and compassionate, her red tongue extended, her eyes alive with power. She watches over the metropolis like a mother over a wild, beloved child.

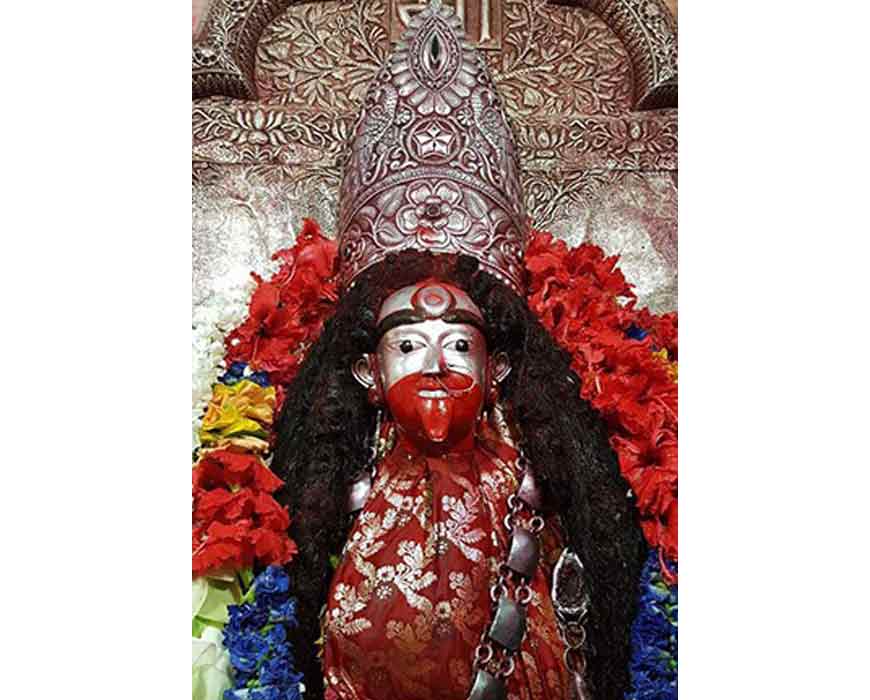

Tarapith

Tarapith

Further north, in Birbhum, lies Tarapith, a place where devotion and darkness coexist. Associated with Maa Tara, a compassionate form of Kali, Tarapith is both temple and cremation ground. Sadhus chant amid burning pyres; women offer hibiscus and milk with quiet faith. It is said that Sati’s third eye fell here, and that her gaze still burns through the veils of illusion.

Kankalitala

Kankalitala

In Birbhum, Bolpur subdivision, there lies another shaktipeeth, i.e., Kankalitala, where the ribs of Sati are believed to have fallen. Unlike the crowded Kalighat, Kankalitala is serene—its temple wrapped in silence and the rustle of sal trees. The Kopai River flows nearby like a quiet hymn. Devotees come not for spectacle but solace. In the simplicity of this place, one feels the heartbeat of Bengal’s ancient faith.

Also read : Bengal is a hotbed of Shakti peeths! Why?

Near Katwa lies Bahula, where Sati’s left arm is said to have fallen. Here the Goddess is gentle, a mother who blesses her children with calm abundance. A few hours away, in Attahas, the laughter of the Goddess still echoes — it is said that her lower lip fell here. The temple sits amidst red soil and green fields, a reminder that even in sorrow, the Mother’s joy endures.

Nalhati

Nalhati

In the quiet town of Nalhati, named after Sati’s fallen throat (nalha meaning throat), the temple rises in simplicity and devotion. Presiding deities of Nalateshwari temple at Nalhati in Birbhum district are Devi Kalika and Yogesh. Fewer pilgrims come here, but those who do speak of a power that is intimate, almost personal. The Goddess here doesn’t roar — she whispers. Her strength lies not in spectacle but in stillness.

The Shaktipeeths of Bengal reveal a truth that the Goddess is both terrifying and tender, destroyer and mother. The skulls around her neck are symbols not of death but of the cycle of rebirth. In Bengal, to worship Shakti is to accept that darkness and light, life and death, are inseparable.

The trail does not end at Tarapith or Kalighat. It continues in the everyday — in the mother lighting a diya at dawn, the girl tying a red thread on her wrist, the devotee whispering a prayer before sleep.

Through Bengal's soil, stories, and people, the Goddess continues to breathe, as the Shaktipeeths remind us. And the trail of Shakti will continue to exist as long as devotion burns like the oil lamp in front of her altar.