Doctor Jack: The Englishman Who Became Kolkata’s Street Healer - GetBengal Story

In 1972, after much violence and significant loss of life, East Pakistan had just become Bangladesh. Radio calls were put out across the world, asking for doctors, nurses and volunteers. As soon as Dr. Jack heard it, he threw some clothes into a bag and hopped on a flight to Bangladesh.

On arrival, he began working immediately in the refugee camps, which at the time were in a terrible state. Faced with a crisis of displaced people and child trafficking, Dr. Jack set up a 90-bed hospital. For women and children, he established the Dhaka Clinic. He even created two farms to provide for the destitute. But the state didn’t take kindly to his efforts. In 1979, after he publicly exposed an international child-trafficking ring, he was expelled from Bangladesh.

There’s a saying in Bengali: “ঢেà¦à¦•à¦¿ সà§à¦¬à¦°à§à¦—ে গেলেও ধান à¦à¦¾à¦¨à§‡” The proverb fit Dr. Jack perfectly. Exiled from Bangladesh, he came to Kolkata—and walked right into yet another crisis. Kolkata then, in the 1970s and 80s, that Mrinal Sen had christened “El Dorado,” that রঘৠরাইয়ের চোখে সà§à¦¥à¦¿à¦° হয়ে আছে যে কলকাতা! Once again, Dr. Jack began his mission of service.

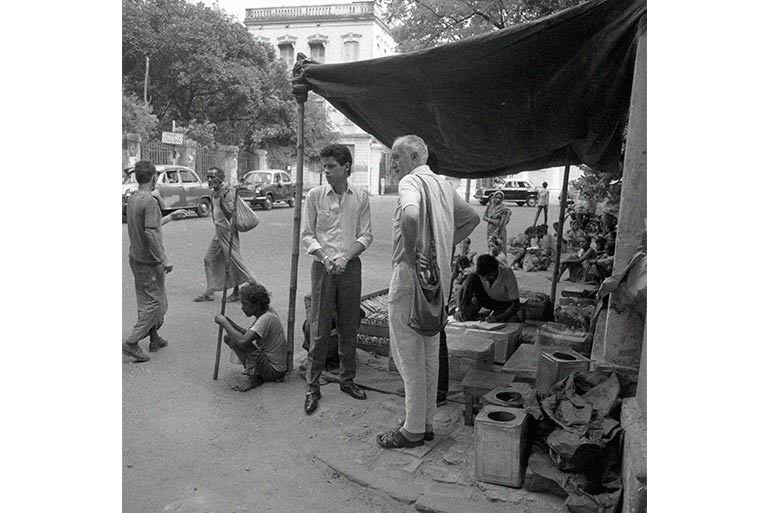

He saw the countless homeless, poor, and sick people living on Kolkata’s streets, in shanties and slums. Nobody cared whether they lived or died. Alone in the city, he constantly reminded himself why he had left his homeland.

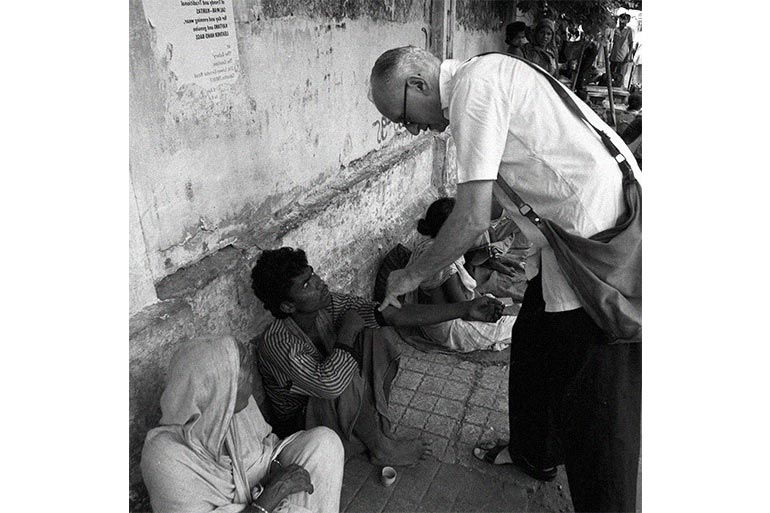

And so, in 1979, with little money in hand, he began treating patients under a flyover on Middleton Lane—right there on the pavement. Passersby saw his work. Gradually, people began offering help—some with money, others by joining in his efforts. Communities that the city’s “respectable” citizens avoided—those forgotten and neglected—slowly became his own. And in their eyes, he became “Jack Dadu”.

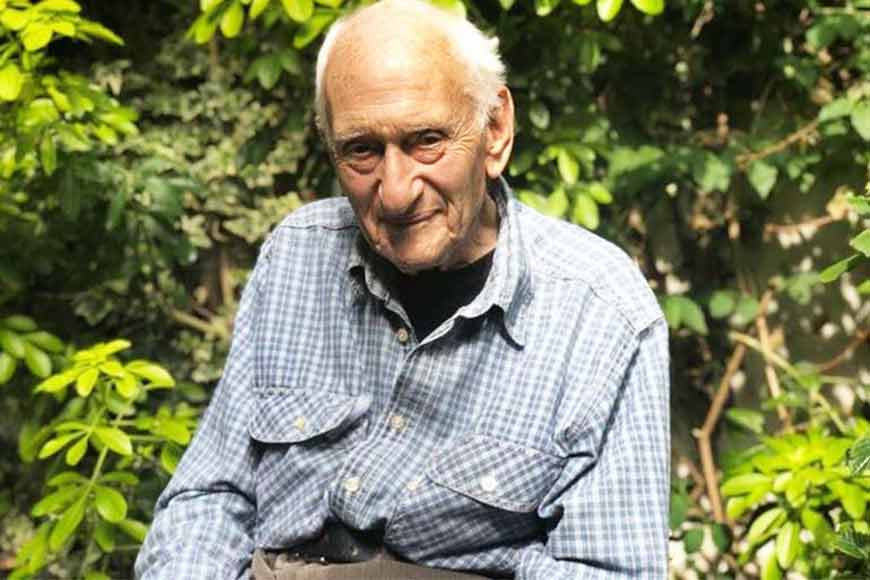

Jack, who was born in the year 1930 in Manchester, attended Oxford University prior to pursuing a life of farming in Cardigan. Then, all of a sudden, he proclaimed that he wanted to be a doctor—to help the poor and helpless. In 1965, he passed the entrance exam and began his studies at the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin, Ireland. After graduating in medicine, he practiced medicine for a period in Bangladesh before heading to Kolkata, where he opened a pavement clinic that grew to be Calcutta Rescue after some time.

To keep the footpath clinic running, he even stood with a tin can, asking for donations from strangers. For 14 years, he worked under that flyover. But over time, his work drew resentment. Some local authorities objected, saying it was illegal to run a clinic this way. Things escalated so far that he was arrested and spent time in Alipore Jail. Though later released on bail, the case dragged on for nine years—until intervention came from none other than mountaineer Edmund Hillary, who helped bring the ordeal to an end.

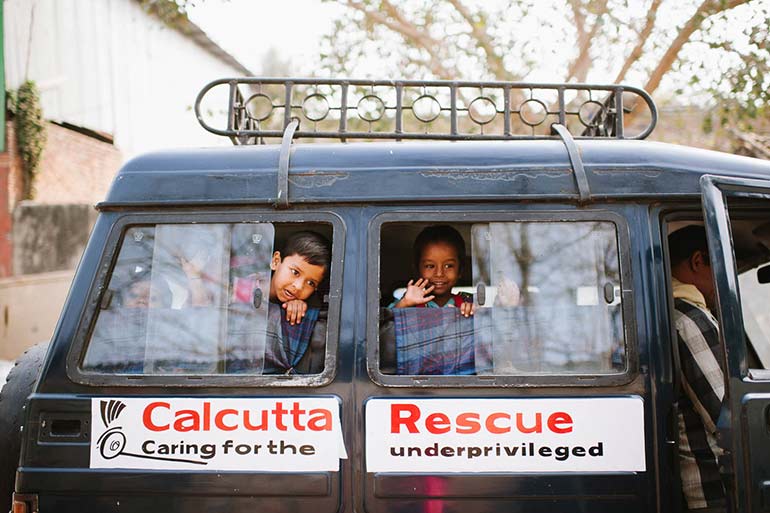

For some time, Dr. Jack also worked with the Missionaries of Charity, but he soon branched out to focus specifically on Kolkata’s slum dwellers. He founded the volunteer organization Calcutta Rescue, which in 1991 received official recognition. Today, the organization runs multiple health clinics, schools, handicraft units, and vocational training centers across Kolkata. Thousands of destitute people receive free treatment for leprosy, tuberculosis, and AIDS.

Dr. Jack’s idea of “Street Medicine” inspired doctors and health workers worldwide, influencing how care is delivered to the marginalized.

As Dr. Alokananda Ghosh, Deputy CEO of Calcutta Rescue’s health department, explained: “We work across three areas—health, education, and livelihood. Our main focus is health, but to truly change lives, we also focus on improving living conditions. For those who couldn’t study due to poverty, we offer vocational training—computer courses, driving, beautician training, and more. Researchers from India and abroad often join us in field projects, conducting surveys that provide valuable evidence on health and social issues.”

Calcutta Rescue also works in arsenic-affected regions. Since 2003, near the Bangladesh border in Malda, they’ve installed filters to provide safe drinking water, covering about 12 villages. Since 2017, they have also been conducting surveys across slums in Kolkata and West Bengal on people’s physical and mental health.

Dr. Ghosh added: “We also work with differently-abled children. About a hundred are registered with us. Along with nutritious food, medicines, and healthcare, we support their education and encourage them to take part in art, music, dance, and sports. Recently, we launched our own diagnostic center—so that instead of patients going elsewhere for tests, we can do it ourselves. We give special care to cancer, TB, and leprosy patients. Regular check-ups in multiple slums have allowed us to detect diseases at early stages, saving many lives. We also plan to expand into more community-based work.”

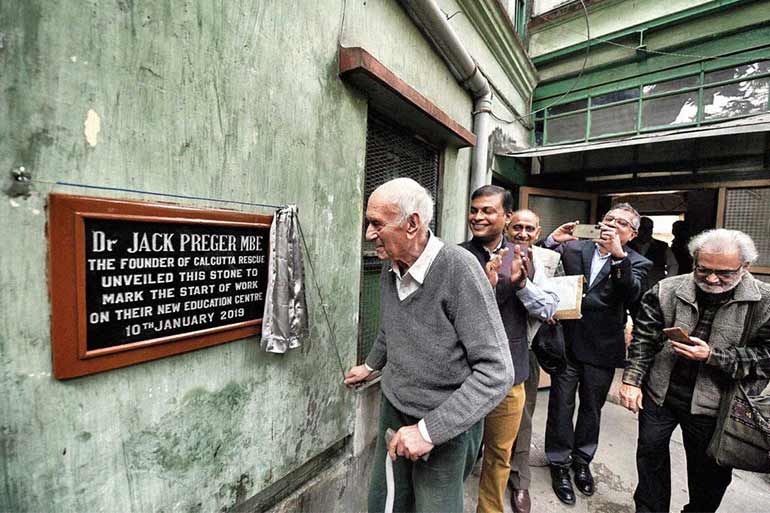

Having spent 40 years of life in Kolkata, Dr. Jack returned home to England in 2019, as he hoped to spend his waning years in Britain. His story inspired filmmaker Benoît Lange, who directed a documentary titled Doctor Jack, produced by Davies Rees. In 1991, Jeremy Joseph also published a book titled Doctor Jack (Bloomsbury, London).

Dr. Jack received the MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) from the UK. In 2017, although he was English by birth, he was honored with "Best Asian." He has received numerous awards and honour over the years.

Calcutta Rescue's main clinic is located in Tala Park, other clinics are located in Nimtala and Tangra. Even if you personally don’t need it, the next time you encounter someone destitute, sick, or homeless on the streets, you can always guide them to Calcutta Rescue. That, at least, is what Dr. Jack would have wished.

Kolkata has not forgotten Jack—and Jack never forgot Kolkata. Even today, under the wing of his organization, the city’s poor and suffering find care. At the age of 94, with fading eyesight and a frail body, Jack still asks from afar:

Note:

Translated by Krishnendu Mitra

To read the original Bengali article, click here.