James Augustus Hicky: The British of Calcutta who spoke against imperial rule

It is always exciting to know the origin of everything. All of us know about India’s fight for its independence from the exploitative British rule. But very few of us know about the first person who raised a voice against such wrongdoings. Well, the man has many such “firsts” in the face of history, which makes him a milestone.

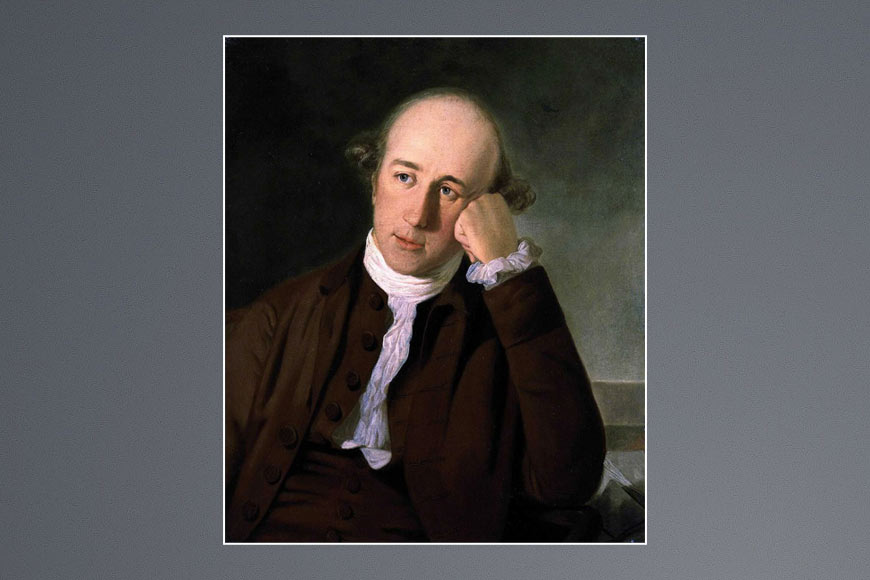

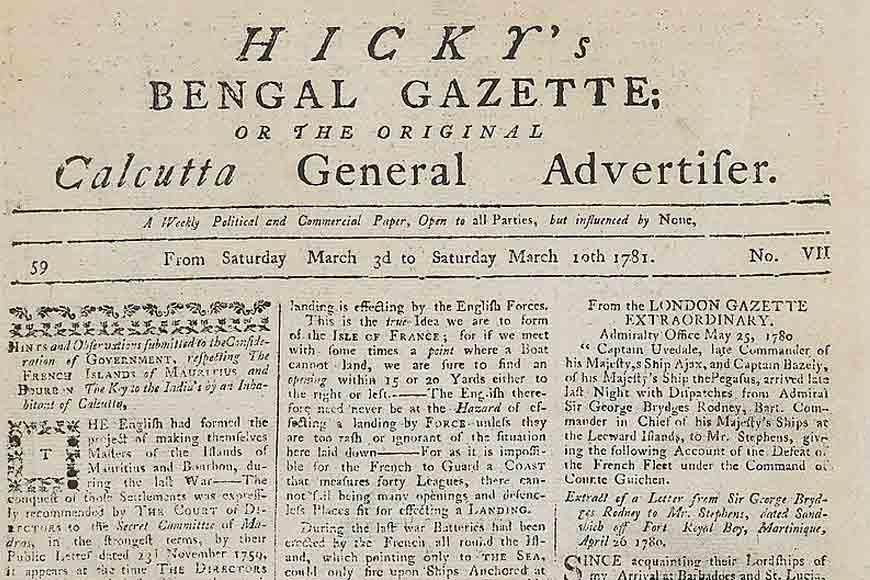

It is ironic that one of our exploiters was the first person to point out the corruptions of the East India Company. In the works of Andrew Otis, “The untold story of India’s First Newspaper,” we find about James Augustus Hicky, the Crusader and Grandfather of Indian Journalism, the first one who talked about the inalienable rights of the British, and one of the very few Britishers who was imprisoned for empathising with Indians. Otis said, “I learned he had founded a newspaper and tried to expose corruption in the British East India Company and embezzlement in the Christian Church. Up against both Church and State, Hicky fought for the freedom of the Press, but his newspaper was shut down. His campaign against corruption and tyranny came to an end, and the East India Company would rule much of India with an iron fist for many years to come.”

James Hicky came to India on 4th April, 1772 with a dream of making huge profits as in those times an average Company servant made far more than the average man in England. When he walked on the land of Calcutta, he got to know all the ways how the British made profits. Everything they did was hoax; they wrote most things on pen and paper while in reality nothing existed.

And what’s more, Hicky started his newspaper ventures in this city of Calcutta. He encouraged Bengalis to fight for the freedom of Press in the face of tyranny as that was the only way out if people have to be informed about their surroundings. “I also found records of Hicky’s earlier life before he became a printer, when he worked as a doctor and surgeon. I learned that he had spent nearly two years in prison before becoming a journalist, and I found clues to why he had become a printer: it was an attempt to pay his debts and get out of jail.”

Hicky had to face a lot of hardships just because he chose to speak against the rampant exploitation. He was criticised by his own people who dreaded him and considered him to be a traitor. Scholars during the British imperial era characterised Hicky as a rogue and scoundrel, a man who undermined the British Empire. Some recent historians have gone too far in the other direction, claiming Hicky’s newspaper was a ‘gem of journalism’, unmatched and unparalleled. He was mostly neglected by historians, who either were not interested in engaging further viewing him as a traitor or did not have enough materials to know about him as information on him was difficult to access, as is evident in the writings of Otis. Due to such neglect, most information on him were wrong, such as his name was misspelled, his place of birth was wrongly stated and some had also included wholly imaginative drawings of him. Most researchers recently have grown more towards Hicky and his works.

Also read : Kolkata was once called 'Black Town'

For example Partha Chatterjee, a historian, has indicated that Hicky has “greater implications: suggesting both that he was the first in India to publicly assert that British subjects had inalienable rights, and that he was the first in India to create a public platform to criticise British rule.”

The long history of printing in Asia was mostly to inform people on taxes or distributing government newsletters, yet Hicky was the first one who found a newspaper, “something that was printed on a regular basis and intended to convey information.” He lived in India and observed the condition of the Indians. His humanity spoke up when he witnessed drastic levels of corruption, exploitation and subjugation. James Hicky wrote a letter to William Hickey begging him for help. William met James in Calcutta’s common jail in Lal Bazar on November, 1777.

James Hicky came to India on 4th April, 1772 with a dream of making huge profits as in those times an average Company servant made far more than the average man in England. When he walked on the land of Calcutta, he got to know all the ways how the British made profits. Everything they did was hoax; they wrote most things on pen and paper while in reality nothing existed. “For example, Richard Barwell made thousands giving himself contracts to run the Company’s salt farms under false names, while the men on Calcutta’s Board of Trade talked openly in public about how they rigged their contracts. One officer encouraged his troops to drink arrack because he made a profit on every bottle sold. Another authorised two officers, one of them his son, to recruit two battalions for the Nawab of Awadh. Neither battalion existed anywhere other than on paper.”

Hicky had to face a lot of hardships just because he chose to speak against the rampant exploitation. He was criticised by his own people who dreaded him and considered him to be a traitor. Scholars during the British imperial era characterised Hicky as a rogue and scoundrel, a man who undermined the British Empire. Some recent historians have gone too far in the other direction, claiming Hicky’s newspaper was a ‘gem of journalism’, unmatched and unparalleled.

Such audacity was handed over to the British by naïve and lazy zamindars, who gradually lost control as they had no future planning and depended entirely on the wage labourers. The history of exploitation had started in India a long time ago, but it reached its peak when the British arrived with their condescending looks at the Indian population. An empire admired by people from different corners of the world. It is a region that was loved by most of its rulers, one of the main reasons why it survived the rule of different communities since the very beginning. Yet it is different in the case of the British as they viewed Bengal and other parts as a profit-making machine rather than a land of culture and love.

Andrew Otis wrote: “This reckless abandon would not last forever. And, although Hicky did not know it yet, he would have a hand in its end. It would be because of him that this impunity, corruption, and arbitrary power would be known to the world.”

Source: Hicky’s Bengal Gazette