From Manipur to Bengal: Purnima Ghosh’s ageless dance journey— GetBengal story

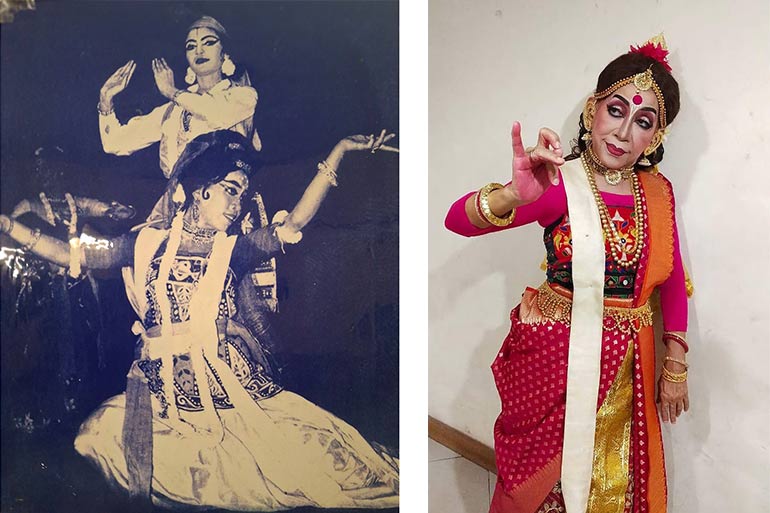

A couple of years ago, a video went viral on social media where a graceful dancer, with effortless movements, told a room full of students: “Here I step into eighty-one.” The moment she said this and performed with such elegance, it was impossible not to be astonished. How could someone past eighty maintain such balance and dance with such vigor? But if it is the legendary Purnima Ghosh, nothing seems impossible.

On the second floor of a building beside the Rashbehari Gurdwara, draped in a black-and-green mekhela and wearing a large bindi on her forehead, Purnima Ghosh bursts into laughter when reminded of that memory. She says, “That was my birthday—May 1st. All my students had come over. I thought, what else could I give them except a dance? So, I performed a Rabindra Nritya. Was it good enough?”

More than just good, that video became a source of inspiration for countless people.

In a society where ageism dominates, where the elderly are often written off, and where women past a certain age are expected to struggle with calcium deficiency, knee pain, and arthritis. For a woman past eighty to dance like that, almost as if flying, is not a small thing. Yet, before reaching eighty, she was once eighteen. How did it all begin?

Purnima recalls: “My father was the renowned Manipuri artist Shri Brajabasi Singh. He came to Kolkata in the 1940s. Many famous personalities of the city, along with their family members, became his disciples. Among his first few students were veteran Bengali film actress Molina Devi, as well as Sheela Haldar, Leela Desai, and Renuka De. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Manipuri dance truly came alive in Kolkata through my father’s efforts.”

A couple of years later, when the bombing of Kolkata began, her father moved with the family to Nabadwip, where many Manipuri families had already settled—and still live today. “I was born in Nabadwip,” she says. “Of course, I also have an elder sister. After about a year and a half in Nabadwip, when my father returned to Kolkata, we settled in the Kalighat area. He then opened a dance school called Nritya Bitan, which flourished for many years. As a child, I too learnt there. My sister and I studied at Mahakali Pathsala. I must admit, I was quite evasive when it came to academics. But meanwhile, I was already dancing on stage. There were times when I was so little that, after stepping on stage, I would look only towards my father sitting in the wings. He would be playing the music and constantly signaling me to turn toward the audience!”

In other words, the Purnima Ghosh we see today was shaped entirely under her father’s guidance. That is only natural—when one’s own father is such a great master, learning is bound to begin at home. Yet, as Purnima herself recalls, her journey was not shaped by her father alone. The influence of many other gurus also came into her life, and it is this collective guidance that has built the dancer she is today.

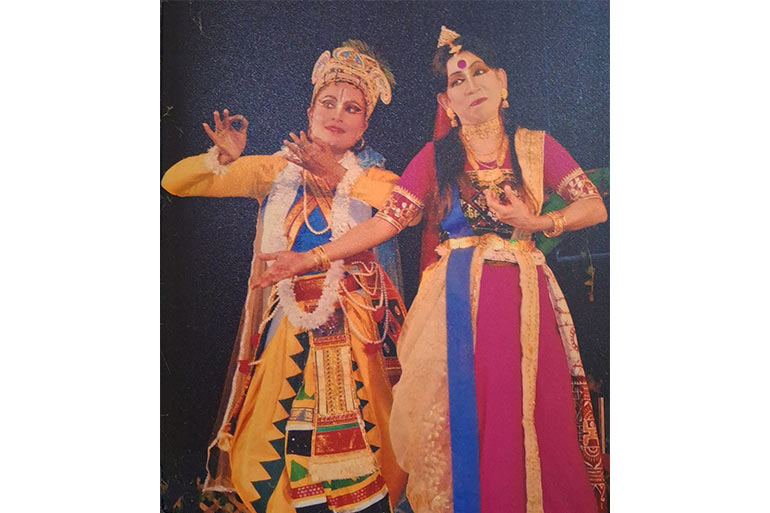

She added, “My father once told me that I needed much more training. In fact, he said this not just to me but to every student of Nritya Bitan. By the way, let me mention my husband, Shri Mihir Kiran Ghosh, who was an architect by profession and a student of B.E. College, also came to learn Manipuri dance from my father. I was just thirteen when I fell in love with that Bengali man, and we married when I turned twenty-one. My in-laws were from Bardhaman, a well-to-do family—we were ‘Ghoti.’ Anyway, alongside Manipuri, I also learned Bharatanatyam. At that time, Guru Maruthappa Pillai had come to Kolkata, and I trained under him. Later, Kathak guru Shri Ram Singh also arrived in Kolkata—he even stayed in our house, and I learned from him as well. Then another Manipuri teacher came from Manipur, Guru T. Nadia Singh, who had joined Rabindra Bharati University—though back then it was called the Uday Shankar Academy or something similar. I received both formal theory and practical training in Manipuri under him. But the one I truly consider my Guru, the one who held my hand till the very end of his life, was the eminent musician and former Principal of Sangit Bhavana at Visva-Bharati, Guru Shri Shailajaranjan Majumdar. He was the one who founded Surangama.”

She also elaborated, “Originally, Shailajada had joined Visva-Bharati as a professor of Chemistry. Later, he met Rabindranath Tagore himself, and it was Tagore who made him Principal of Sangit Bhavana. After retiring from there, around 1960, he started Surangama right here in Kolkata—at exactly the spot where you and I are sitting now. The first building was at the back, and after this place was rebuilt, we shifted upstairs here. Alongside him were Shri Prasad Sen, and Indira Devi Chaudhurani also came a few times, if I remember correctly, while Surangama was being set up, just before she passed away. I joined here in 1962, and from then on, I stayed. I never went anywhere else.”

Dancer Purnima Ghosh never opened a school of her own. Because Shailajaranjan Majumdar had once told her, “Purnima! Surangama is yours alone.” Even today, whenever someone comes to learn—be it a regular class or a special one—Purnima always tells them to come to Surangama.

Purnima Ghosh, her dance, and her artistry are known not only in Bengal but across India. Yet she is not just an artist—she is also a homemaker. In our country, the lives of women artists are seldom easy. To keep their art alive, they must face many hurdles, struggles, and resistance. Did Purnima Ghosh not encounter such obstacles? Was her life a bed of roses?

When asked, Purnima once again breaks into her famous laughter and drifts back into the past. She says, “When I first went to my in-laws’ home in Burdwan, the entire village came to see that a ‘Chinese bride’ had arrived! There has always been a kind of coexistence between Manipuri and Bengali culture. My in-laws, especially my mother-in-law and my brother-in-law, always respected my dance. And my husband—he was by my side throughout. In fact, many times he played the hero opposite me in dance dramas. I managed both household duties and dance with equal devotion. I have two daughters—the elder, Aindrila, is a dancer, while the younger, Chandrayee, is an actress. From preparing their school tiffin to cooking for the family, to supervising their studies—I did everything single-handedly. And I never found it difficult. You see, Manipuri blood runs in my veins. Manipuri women are extremely hardworking. I had seen my own mother balance her household while dancing beautifully! That tradition lives in me as well. Alongside dance, I even ran a boutique. Now, most of my students are between thirty-five and seventy. They come to me not just to learn dance, but to learn life itself—that’s what they tell me. My day begins early. I do small household chores in the morning. After lunch, I always take an hour’s nap. And every day, from four to seven in the evening, I come here to Surangama. I have a pacemaker in my chest. Just two months ago, I had hip-bone surgery. Yet, I never feel any exhaustion when I dance.”

It is for all these reasons that Purnima Ghosh has become a source of inspiration for so many. She studied Manipuri, and even today she teaches Bharatanatyam. And of course, there is Rabindra Nritya. But does the present state of Rabindra Nritya satisfy her?

She replies, “Rabindra Nritya is a century-old art form. It was formed even before the Uday Shankar style of dance. It is truly the dance form of the Bengali people. With Shailajadar’s encouragement, I had also learnt a few foreign dance styles—like Kandy and Java—and not only learnt them, but also applied them within Rabindra Nritya. Our lineage has been universally acknowledged. Perhaps, in the name of Rabindra Nritya, many poor performances are staged which do not follow its true philosophy. Still, I would say—it is the responsibility of the seniors to guide others on what is right and what is not, isn’t it? Besides, this era is moving at a tremendous pace, everything is going online. But dance is a discipline that must be learnt directly from the Guru; there is no other way. There are many dance competitions on television, and they have their place. But with makeshift arrangements or shortcuts, you cannot truly create dance. And you never will.”

Behind her seemingly cheerful personality lies a serious philosopher, a researcher, and above all, a deeply experienced dance teacher—that much becomes clear when one listens to Purnima Ghosh’s words. May she remain just as she is. Not only at eighty-four, but even when she steps into a hundred, may the accomplished, graceful, and erudite Purnima Ghosh of Surangama continue to dance in the same spirit.

Note:

Translated by Sabana Yasmin

To read the original Bengali article, click here: