Back to ‘saheb para’, the heart of White Calcutta

Having ended last week’s walk at Hatibagan, from where you can take the Metro from Shyambazar station and travel back to Esplanade. As you emerge from the Metro station, you will be stepping back into the neighbourhood which once lay at the heart of British Calcutta. Little of the ambience remains other than some magnificent commercial buildings and a few other typically British institutions such as churches and cemeteries.

Point A - Whiteaway Laidlaw/ Metropolitan Building

Known as the Whiteaway Laidlaw department store at the beginning of the 20th century, this was one of Calcutta’s most prestigious shopping destinations, which opened its doors to the public in 1905. The neo-Baroque structure with its domes, a clock tower and arched recessed windows, looked the part too. Post-Independence, the ownership of the building passed on to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., which is when it began to be popularly referred to as the Metropolitan Building.

In 1991, the top floor of the building was ravaged by a fire, which destroyed the iconic Bourne & Shepherd photography studio, until then one of the world’s oldest operational photography studios, along with countless priceless old photographs which took with them a large chunk of Kolkata’s history.

In 2012, the dilapidated yet gorgeous building was finally renovated by the Life Insurance Corporation of India, and it still houses a commercial complex. The fresh coat of white and gold paint and renovations to both the exterior and interior structure have largely reinstated the building’s lost glory, and the handicraft emporium on the ground floor recalls the swanky department store that once occupied the premises.

Point B - Jan Bazar, S.N. Banerjee Road

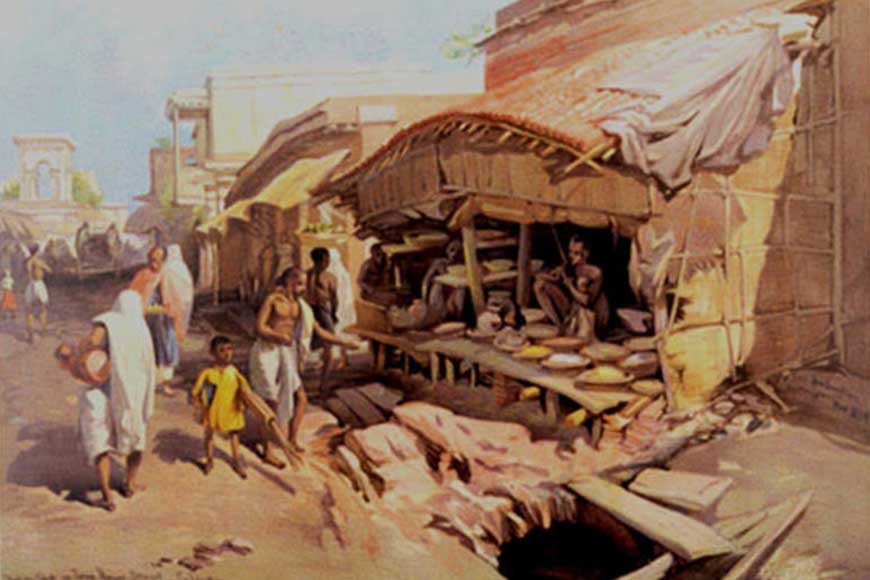

As mentioned in one of our previous articles, Jan Bazar is actually a desi version of John’s Bazar, which formed part of the British-Indian administration’s revenue zone in the 18th and 19th centuries, when many such bazars were owned by Europeans. The bazar is in the vicinity of the huge red-brick structure of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation, which is why the road was called Corporation Street earlier, and was renamed Surendranath Banerjee Road post-Independence after one of India’s foremost nationalist leaders. Walking past this edifice, you can actually smell Jan Bazar before you reach it, a wonderfully evocative aroma of spices of every possible description.

Old chronicles tell us that in the 19th century in particular, the neighbourhood became a sort of ‘live entertainment’ hub, with women singers and dancers entertaining clients at their place of business. Inevitably, this facilitated the growth of several taverns and drinking joints too, the sole remnant of which today is a seedy country liquor outlet, which generates its own aroma across the neighbourhood.

Point C - Rani Rashmoni’s Residence

Walking past Jan Bazar, at the crossing of Free School Street stands a complex of three buildings. The part of Free School Street now called Rani Rashmoni Road houses Rashmoni’s former personal residence. The entire complex was completed between 1813 and 1821, and reportedly comprised nearly 300 rooms, testifying to the enormous wealth and influence of Rani Rashmoni, one of the most remarkable figures of 19th century Bengal. Married to Rajchandra Das of the Jan Bazar zamindar family, she lost her husband in 1836 when she was 43. Not only did she not give in to grief, but took over her husband’s business interests and entered headlong into conflict with the British administration, quite often getting the better of her opponents.

The family fortune thrived under her care, and as a devotee of Sri Ramakrishna, Rashmoni spent Rs 9 lakh in the 1850s on the construction of the spectacular Dakshineswar Temple complex. Ramakrishna himself would often visit the rani’s personal residence, performing puja at her ‘thakur dalan’.

Read the earlier episodes of our walk :

Enjoy the lockdown with your very own customised Kolkata Walk

A little bit of BBD Bag, a whole lot of Calcutta

Esplanade, the beating heart of old Calcutta

The places of worship in old Calcutta, and what we learn from them

Walk on for a perfect balance of religion and commerce

On the waterfront: a walk along the Hooghly

Walking around the ‘native’ palaces of Kolkata

A walk down Sealdah and Bowbazar, among the oldest areas of Kolkata

Walking through the centre of Kolkata

Old Calcutta’s temple trail, a cultural odyssey

Lost in obscurity, Calcutta’s oldest surviving temples

Walking down College Street, home to temples of learning

From Kali to Jagannath to Star Theatre, a walk to remember

Even today, the relatively dilapidated building manages to convey a sense of its former magnificence. The two other sections of the house too, show glimpses of their past glory, and taken together, the complex is still impressive and definitely worth a visit, though some parts of it are private residences.

Point D - New Market

The erstwhile Stuart Hogg Market, named after the man who was both Commissioner of Calcutta Police and Chairman of the Calcutta Corporation for a time, was completed in 1874. The location it was built on was earlier home to a market called Fenwick’s Bazar in the 1780s. The street it stands on was (and still is) known as Lindsay Street, named after Robert Lindsay (1754-1836), whose long and chequered career saw him assume the office of magistrate, dabble in shipbuilding, and even fight as a soldier. Officially named Nellie Sengupta Sarani after the wife of Deshapriya Jatindramohan Sengupta, its earlier name is nevertheless still strong in popular memory.

The British government commissioned Richard Roskell Bayne, an architect employed with the East Indian Railway Company, to design the Victorian Gothic market complex, and upon completion, Bayne was honoured for his achievement with an award of Rs 1,000. The builders were Mackintosh Burn. Having begun life as ‘New Market’, the complex was renamed after Sir Stuart Hogg in 1903, and Bengalis began calling it Hogg Saheber Bajar, though its earliest name is what has stuck. New Market's growth kept pace with the city until World War II. The northern portion of the market came up in 1909 at a cost of Rs 6 lakh, and the market’s much talked about clock tower at the southern end was shipped over from Huddersfield in the UK and installed in the 1930s.

As you explore the many charms of the market, which still draws shoppers from all parts of India, and occasionally the world, we will take the opportunity to plan the next instalment of our walk, which will take us toward Park Street.