Lakshmiswar Singh: A forgotten craft teacher and Esperanto Expert of Santiniketan

Established in 1863 to help education go beyond the confines of the classroom, Santiniketan grew into the Visva Bharati University in 1921, attracting some of the most creative minds in the country. From its very inception, Santiniketan was lovingly modelled by Tagore on the principles of humanism, internationalism, and a sustainable environment. He developed a curriculum that was a unique blend of art, human values, and cultural interchange. As one of the earliest educators to think in terms of the global village, he envisioned an education that was deeply rooted in one’s immediate surroundings but connected to the cultures of the wider world.

Located in the heart of nature, the school aimed to combine education with a sense of obligation towards the larger civic community. Blending the best of Western and traditional Eastern systems of education, the curriculum revolved organically around nature with classes being held in the open air. Tagore invited artists and scholars from other parts of India and all over the world to live together at Santiniketan and share their cultures with the students of Visva Bharati.

In 1921 Rabindranath Tagore bought a large manor where he set up the Institute of Rural Reconstruction in 1922 with Leonard Knight Elmhirst as its first director. Rathindranath Tagore, Santosh Chandra Mazumdar, Gourgopal Ghosh, Kalimohan Ghosh, and Kim Taro Kasahara joined Elmhirst. The second but contiguous campus of Visva Bharati was subsequently located around the same place in 1923 and it came to be known as Sriniketan. Silpa Bhavan at Santiniketan had already started training in handicrafts including pottery, leatherwork, batik print, and woodwork. Sriniketan took over the work to bring back life in its completeness to the villages and help local villagers to solve their problems instead of having solutions being imposed on them from outside.

In 1928, during his stay in Stockholm, Lakshmiswar met famous novelist Selma Lagerlof and joined the Esperanto movement. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist, L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, Esperanto was intended to be a universal second language for international communication, or “the international language” (la Lingvo Internacia). Within a short time, Lakshmiswar became an Esperantist and passed all SEI examinations.

Tagore went globe-trotting to look for prominent figures of the literary and cultural world and invite them to visit his institution at Santiniketan. He encouraged gifted artists and craftspeople to take up residence at Santiniketan and devote themselves full-time to promoting a national form of art and craft. He was instrumental in gathering notable artists, art historians, sculptors, and luminaries from the creative sphere who were hand-picked by the poet himself and included stalwarts like Asit Kumar Haldar, Stella Kramrisch, Nandalal Bose, Surendranath Kar, Benode Bihari Mukhopadhyay and many more. They gave shape to Tagore’s vision of the place of art and craft in education and art as an essential part of the culture.

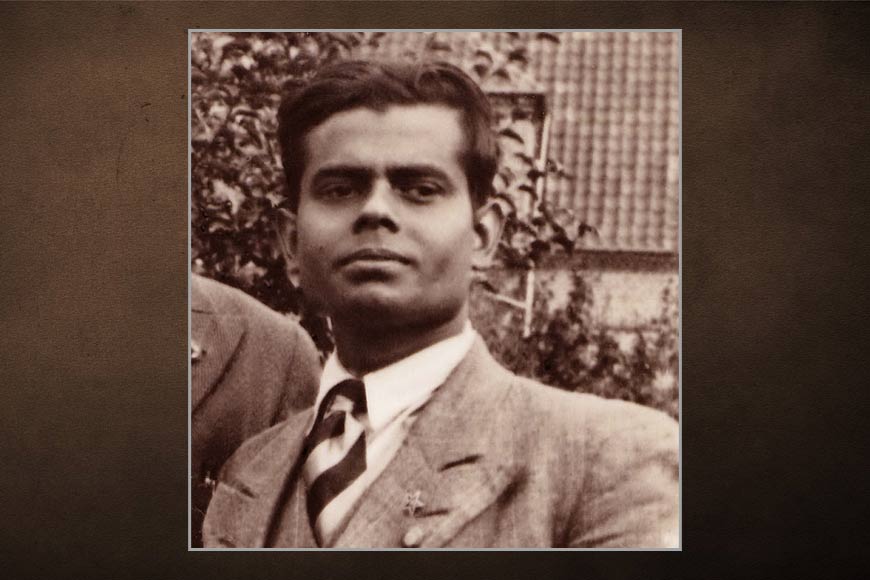

One such gifted craftsperson who was hand-picked by Tagore was Lakshmiswar Singh (June 6, 1905, to April 22, 1977), a brilliant wood crafter from Rarisal in North-East India. It is a pity that we have simply forgotten this famous craftsman who excelled in wood-crafting. Born into a landed gentry at Rarisal, Lakshmiswar showed signs of his talent early in life. The poet was very fond of Lakshmiswar and his style of crafting and he introduced him as a teacher at Santiniketan and encouraged him to teach his craft. Singh taught at both Sriniketan and Santiniketan for a long time. He also played an important role in the promotion of Esperanto, the international language, in this country.

From an early age, Lakshmiswar watched rural woodcarvers in his village etch fascinating designs and panels depicting stories from epics and fairy tales. He started taking lessons from them and soon mastered the craft. In 1922, he joined Sriniketan, then headed by agro-economist Leonard K. Elmhirst. In 1925, he wrote a monograph on woodcraft education titled, ‘Kather Kaajer Boi’ (Book on Woodworks) which was published by Visva-Bharati Press. Rabindranath himself wrote the preface of the book. Lakshmiswar taught for three years in both Santiniketan and Sriniketan.

In 1928, Rabindranath took the initiative to send Lakshmiswar to Sweden to get international exposure and also train in the handicraft-based pedagogic system called sloyd. He got admission to the sloyd institute and obtained a three-year advanced diploma. On his return to India, he was immediately appointed as a teacher of woodcraft in Santiniketan. But due to the acute funds crunch, it was becoming well neigh impossible to set up the infrastructure for the craft swing. A few years later, Lakshmiswar went back to Sweden to set up a self-sufficient craft learning center at Santiniketan.

This was around 1931- 9933 when Europe was reeling under the Depression. Rabindranath wrote a letter to Countess Kerstin Hamilton seeking technical and financial assistance for the vocational training project he wanted to establish at Sriniketan and sent it to her via Lakshmiswar. The countess immediately responded and arranged for two well-trained Sloyd teachers, Ms. Jeanson and Ms. Cederblom, whom she sent to Santiniketan. The two teachers introduced several new styles at Santiniketan. Countess Hamilton also visited Santiniketan in 1936 with her artist son, Herbert Hamilton. Lakshmiswar returned to India the following year. That very year, Silpa Sadan was officially inaugurated at Sriniketan and Lakshmiswar joined the vocational training unit as Head of the Department. In 1938, at the behest of Mahatma Gandhi, he joined Seva Gram B.T. College as Professor. After Rabindranath's demise in 1941, he returned to Santiniketan and devoted himself to the development of handicrafts.

In 1928, during his stay in Stockholm, Lakshmiswar met famous novelist Selma Lagerlof and joined the Esperanto movement. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist, L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, Esperanto was intended to be a universal second language for international communication, or “the international language” (la Lingvo Internacia). Within a short time, Lakshmiswar became an Esperantist and passed all SEI examinations. At the initiative of Ernfrid Malmgren, he began a lecture tour in September 1929. He traveled extensively in Sweden, covering over 10,000 km, delivered more than 200 lectures to more than 30,000 people, and twice on the radio. In the autumn of 1930, he toured in Estonia and Latvia, then for two months in Poland, attending 40 conferences in 22 cities and addressing nearly 8000 people. In August 1931, he returned to India, where he worked for Esperanto, writing articles and becoming the chief delegate of the Universal Esperanto Association (UEA).

One such gifted craftsperson who was hand-picked by Tagore was Lakshmiswar Singh (June 6, 1905, to April 22, 1977), a brilliant wood crafter from Rarisal in North-East India. It is a pity that we have simply forgotten this famous craftsman who excelled in wood-crafting. Born into a landed gentry at Rarisal, Lakshmiswar showed signs of his talent early in life.

In the autumn of 1933, he again went back to Sweden. In 1936, he published his book, "Hindo Rigardas Svedlandon" (An Indian Looks at Sweden). His translation of seven stories of Tagore, "Malsata Ŝtono" (A hungry stone) was first published in the 1961 Serio Oriento-Okcidento. He wrote a book in Bengali called, 'Esperanto Sahajpath'.

The result of his efforts to create an Esperanto movement in India was the foundation of Bengala Esperanto-Instituto (Bengali Institute of Esperanto) in 1963 when his pamphlet appeared in Bengali Esperanto-Movado (Esperanto Movement). Eldona Societo Esperanto (Enterprise Edition Esperanto), Sweden, published Lakshmiswar’s autobiography, Jaroj Sur Tero (Years on Earth) in 1966. His other works include Sloyd Handicraft, Educational Arts and Corpus Science, Esperanto Movement, Swedish Flora and Fauna. His last work was published in 1974, ‘Facila Esperanta Lernolibro’ (Easy Esperanto Primer), in Bengali.

Beyond his artistic identity, Lakshmiswar is remembered far more articulately in the Esperanto community than in the context of India's journey to modernity.